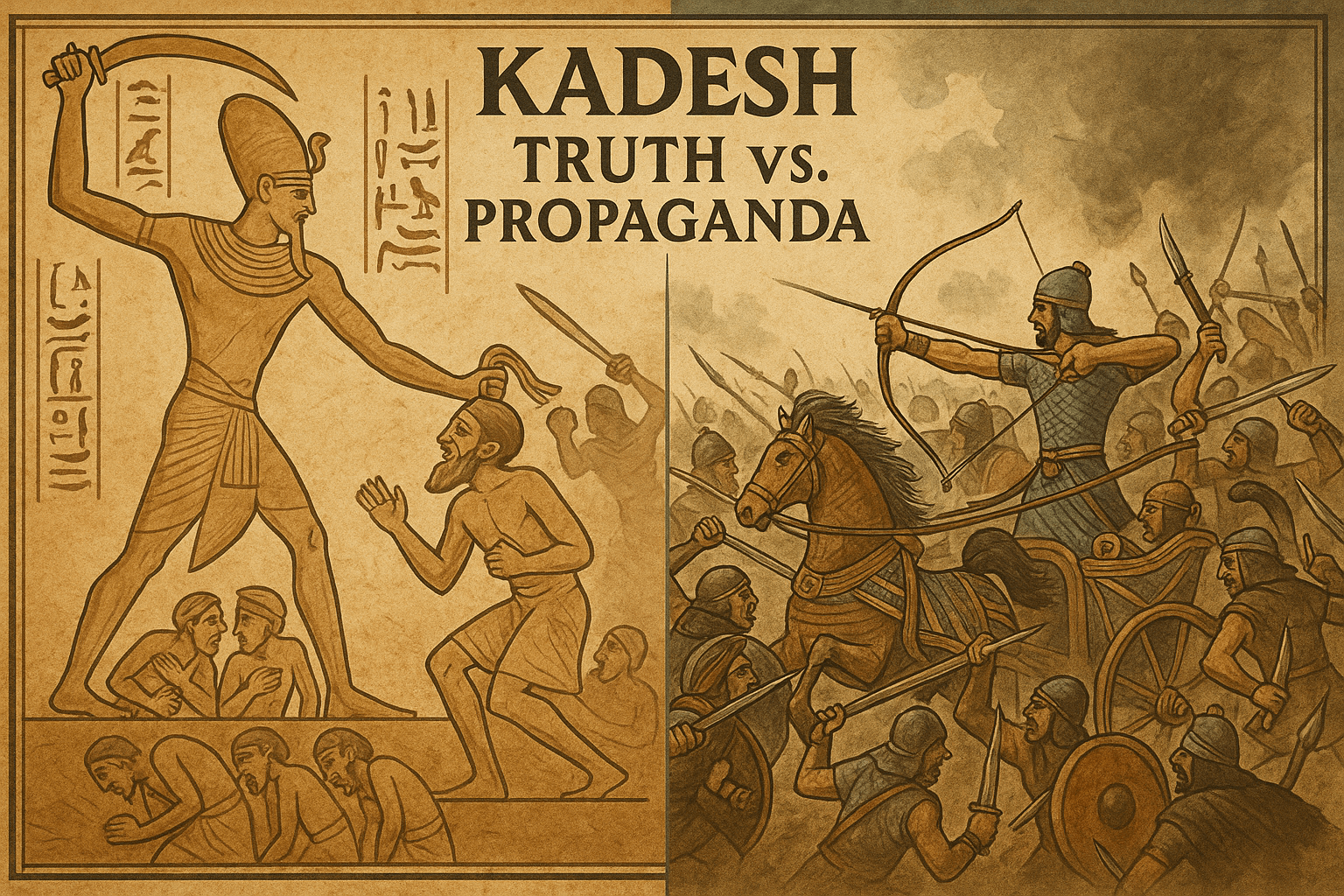

What happened on that fateful day has been debated for millennia, not because of a lack of evidence, but because we have two powerful, competing narratives. On one side, we have the Egyptian account of a stunning, divinely-inspired victory. On the other, the Hittite records paint a very different picture. By examining these sources, we can unravel one of history’s greatest propaganda campaigns and ask the crucial question: who really won the Battle of Kadesh?

The Egyptian Account: A Tale of Divine Triumph

If you were a subject of Ramesses II, you couldn’t escape his version of the battle. The pharaoh commissioned a grand, heroic narrative of the event to be carved in stone on the walls of Egypt’s most sacred temples, from Karnak and Luxor to his own mortuary temple, the Ramesseum, and the magnificent Abu Simbel. This story comes in two forms: the detailed “Poem” and the more concise “Bulletin.”

According to Ramesses, the story unfolds like a Hollywood blockbuster:

- The Deception: As the Egyptian army, divided into four divisions named after the gods Amun, Ra, Ptah, and Set, marched north, they encountered two Bedouin nomads. These men, actually Hittite spies, claimed the Hittite army was terrified of the approaching pharaoh and was still hundreds of kilometers away in Aleppo.

- The Ambush: Ramesses, buoyed by this news, forged ahead with only his lead division, the Amun, and set up camp just northwest of Kadesh. The rest of his army was strung out and far behind. It was a catastrophic intelligence failure. The Hittite army wasn’t in Aleppo; it was hidden just behind the city of Kadesh.

- The Crisis: As the Ra division marched to join the pharaoh, 2,500 Hittite chariots crashed into their flank, shattering the formation. Panic-stricken soldiers and chariots fled north, crashing into Ramesses’ unprepared camp and spreading chaos. The pharaoh was suddenly isolated, his army collapsing around him.

“I found myself surrounded by 2500 chariots, and all the swiftest of the Hittite host… I was all alone, no other was with me. My infantry and my chariotry forsook me in fear.” – Excerpt from the Kadesh “Poem”

This is the moment the narrative pivots from military disaster to personal, divine heroism. Abandoned and surrounded, Ramesses prayed to the god Amun. Filled with divine power, he single-handedly charged the Hittite lines not once, but six times. Like a living god of war, he drove the enemy into the Orontes River, his fiery presence alone turning the tide. The timely arrival of a separate elite force, the Ne’arin, helped trap the remaining Hittites, and the day was saved. The Egyptians claimed the Hittites were so thoroughly beaten that their king, Muwatalli II, immediately sued for peace.

The Hittite Perspective: A Quiet Victory

The Hittites didn’t carve epic poems on their temple walls. Their records, found on clay tablets in the ruins of their capital, Hattusa, are more administrative and far less dramatic. They don’t provide a blow-by-blow of the battle. Instead, they focus on the strategic outcome.

The Hittite account implicitly refutes Ramesses’ story. Far from being a crushing Egyptian victory, the battle is portrayed as a successful Hittite defense. Their primary objective was to stop the Egyptian advance and maintain control over their Syrian territories. In this, they succeeded.

If Ramesses had won such a glorious victory, why did he fail to capture the prize, Kadesh? Why did his army immediately turn around and march back to Egypt? Hittite records show that not only did Kadesh remain firmly in their sphere of influence, but in the years immediately following the battle, the Hittites actually expanded their control in the region, quelling rebellions and consolidating their power. This is not the action of a defeated empire.

Reconstructing Reality: Who Really Won?

When we place the two accounts side-by-side, the truth begins to emerge. The Battle of Kadesh wasn’t a single victory or defeat, but a conflict with three different outcomes.

- The Tactical Outcome: A Draw. Ramesses’ leadership on the day of the battle was genuinely remarkable. He fell for a brilliant Hittite trap and his army was on the verge of annihilation. His personal courage and ability to rally his forces from the brink of disaster turned a certain defeat into a bloody stalemate. He survived, but he didn’t win.

- The Strategic Outcome: A Hittite Victory. Egypt failed in its campaign objective. They did not take Kadesh. They gained no territory. The border between the two empires remained largely unchanged. The Hittites successfully defended their frontier and checked Egyptian expansion. By any strategic measure, this was a win for Muwatalli II.

- The Propaganda Outcome: An Overwhelming Egyptian Victory. This is where Ramesses II proved to be a true genius. He returned to Egypt and launched one of the most successful public relations campaigns in history. By portraying the battle as a personal triumph where he, with the help of the gods, single-handedly defeated a massive enemy, he cemented his image as a warrior pharaoh. His narrative completely ignored the strategic failure and focused entirely on his moment of personal glory. For centuries, his was the only story told.

The Aftermath: The World’s First Peace Treaty

Perhaps the most telling piece of evidence is what happened 16 years later. After years of continued border skirmishes, the two empires, now facing a new threat from the rising power of Assyria, decided to make peace. Around 1258 BCE, Ramesses II and the new Hittite King, Hattusili III, signed the Treaty of Kadesh.

Copies from both sides have been found—a silver tablet in Egypt and clay tablets in Hattusa. It is the oldest known international peace treaty in existence. It established a formal peace, defined their mutual border in Syria, and included a mutual defense pact. You simply do not sign a treaty of equals with a foe you have supposedly crushed into submission.

The Battle of Kadesh teaches us a powerful lesson about the past. It shows that history isn’t just about what happened, but about who gets to tell the story. Ramesses II may not have won the war for Kadesh, but by controlling the narrative so masterfully, he won the war for his own legacy, ensuring he would forever be known as Ramesses the Great.