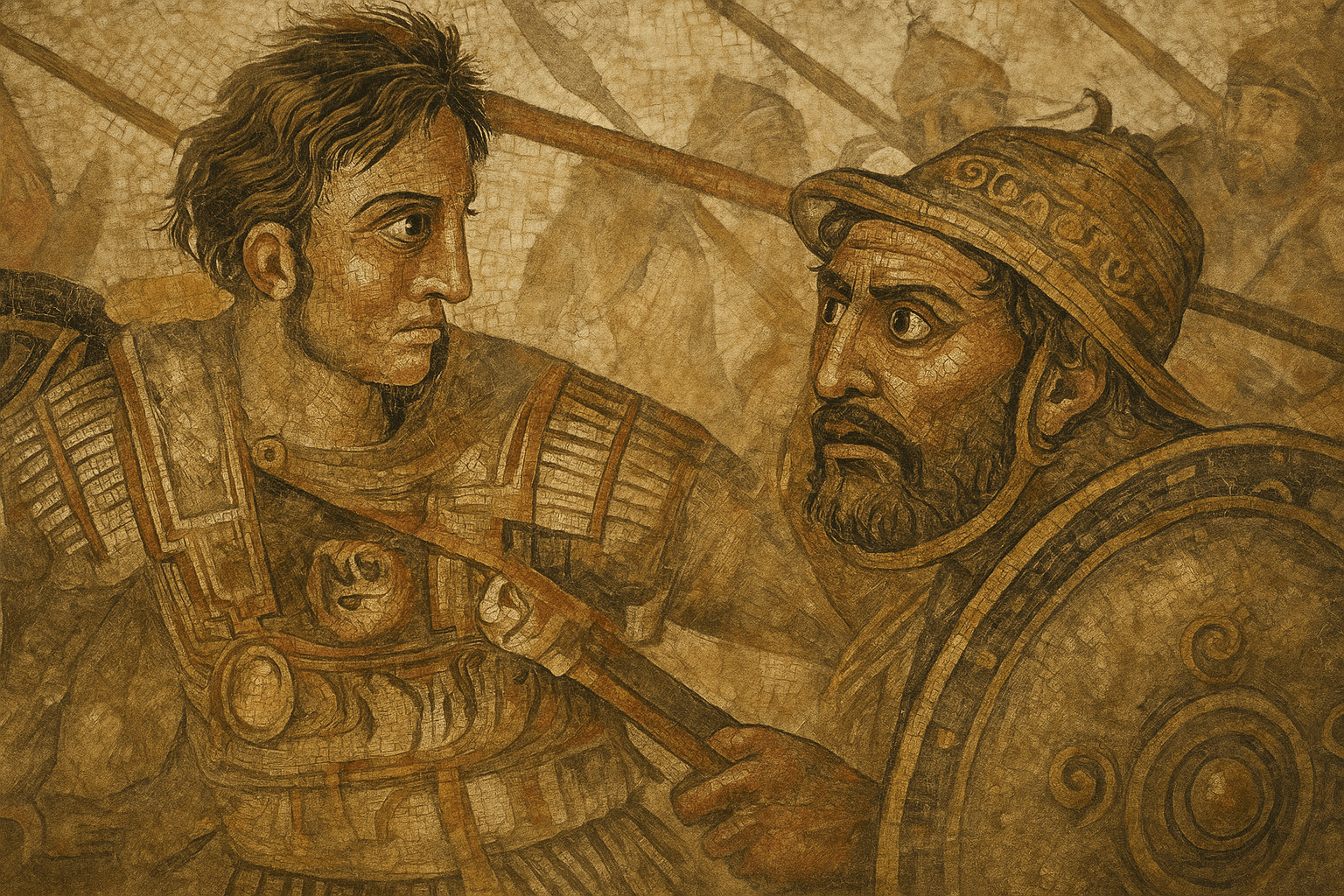

Frozen in time by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, this incredible artwork is more than just a durable floor decoration. It is a direct, high-fidelity window into the lost world of ancient Greek painting, a visceral document of ancient warfare, and a masterful piece of political propaganda.

A Masterpiece Preserved in Volcanic Ash

Discovered in 1831, the Alexander Mosaic measures a staggering 5.82 by 3.13 meters (19 ft × 10 ft) and is composed of an estimated 1.5 million tiny, colored tiles, or tesserae. The sheer scale and detail are astonishing, especially considering its location—not in a public building, but on the floor of a reception room in a private home. This tells us about the immense wealth of the Pompeian elite and their desire to associate themselves with the grandeur of Greek culture and history.

What makes the mosaic truly priceless, however, is that it is believed to be a remarkably faithful copy of a lost Hellenistic panel painting from the late 4th century BC. Ancient writers like Pliny the Elder praised Greek painters such as Apelles and Philoxenus of Eretria for their realism and drama, but virtually none of their work survives. The Alexander Mosaic is our closest link to these lost masterpieces, a Roman echo of Greek genius. The artist used a limited four-color palette (yellow, red, black, and white) to create a work of stunning complexity, modeling, and emotional depth, proving that you don’t need a full spectrum to create a photorealistic effect.

The Decisive Moment: Alexander vs. Darius

The mosaic depicts a single, pivotal moment in a massive battle, widely believed to be the Battle of Issus in 333 BC (though some argue for Gaugamela in 331 BC). This was the clash where Alexander the Great’s smaller Macedonian force decisively broke the army of the Persian King Darius III.

On the left, we see Alexander, charging forward on his famous steed, Bucephalus. He is the image of youthful, heroic fury. He wears no helmet, a common feature in his iconography, suggesting his supreme confidence and divine protection. His eyes are locked onto his target, his spear poised to strike. His chest is adorned with a breastplate featuring the Gorgon Medusa, an apotropaic symbol meant to ward off evil and petrify his enemies.

In the center-right, the scene’s emotional core, is Darius III. Standing in his war chariot, he is the picture of horrified shock. But crucially, he isn’t looking at Alexander. His gaze is fixed on one of his loyal bodyguards, a young nobleman who has just been speared (likely by Alexander himself) to save the king. Darius’s arm is outstretched in a gesture of helpless grief and alarm. The chariot driver is frantically whipping the horses to turn and flee, a maneuver that is throwing the entire Persian battle line into disarray.

A Revolution in Ancient Art

This is no static, frieze-like depiction of battle. The artist employed revolutionary techniques to create a scene of unparalleled dynamism and psychological realism.

- Dramatic Composition: The entire scene is built on powerful diagonals. The forest of Persian spears on the right points upwards, creating a sense of a dense, impenetrable wall, while Alexander’s low, driving spear thrust from the left cuts through it, symbolizing the shattering of the Persian line.

- Foreshortening and Depth: To create a sense of three-dimensional space, the artist masterfully used foreshortening—the technique of depicting an object at an angle to create the illusion of depth. The most famous example is the horse in the center, shown from the rear, its rump facing the viewer. This radical perspective pulls the observer directly into the chaos of the battlefield.

- Light, Shadow, and Reflection: The use of shading, or skiagraphia, gives volume and weight to the figures. But the artist’s greatest boast is a small, almost hidden detail on the ground. A fallen Persian’s face is not shown directly, but as a faint, terrified reflection in the polished surface of a discarded shield. This level of sophisticated realism was unprecedented and speaks to the immense skill of the original painter.

- Psychological Drama: More than anything, the mosaic captures emotion. It’s a snapshot of human experience in the face of death: Alexander’s determined fury, Darius’s panicked grief, the fear in the horses’ wide eyes, and the desperation of the dying.

The Art of War and Propaganda

The mosaic is a superb historical document on ancient warfare. It vividly illustrates the clash between the Macedonian cavalry charge and the grand, chariot-led Persian army. The ground is a brutal landscape of discarded helmets, broken shields, and fallen men, a stark reminder of the bloody reality of close-quarters combat. The artists did not shy away from the violence.

Yet, this is far from an objective report. It is a masterful piece of propaganda, designed to glorify Alexander. He is the unstoppable force of nature, the bare-headed hero who personally leads the charge and breaks the enemy king. Darius, while portrayed with a degree of sympathy for his personal grief, is ultimately shown as the defeated leader whose flight causes the collapse of his own army. The narrative is clear: the disciplined, heroic leadership of the West triumphs over the chaotic, decadent East. The original painting was almost certainly a commission to celebrate and solidify Alexander’s victory.

Centuries later, the Roman owner of the House of the Faun chose this specific scene to display in his home. By doing so, he was aligning himself with the legacy of the world’s greatest conqueror, projecting an image of culture, power, and a connection to the glorious Hellenistic past.

The Alexander Mosaic is a technical showpiece, a dramatic narrative, and a political statement all rolled into one. It captures the raw energy of a single historical moment with a level of artistry and emotional power that continues to captivate us two thousand years later, reminding us that a great work of art can be the most powerful history book of all.