The phrase “Parthian shot” has trickled down through history to mean a sharp, final remark delivered as one is leaving. But its origin lies in a very real, very deadly military tactic that culminated in one of the most shocking and humiliating defeats in the annals of the Roman Republic. In 53 BC, deep in the desolate plains of Mesopotamia, a Roman army led by one of its most powerful men was not just defeated—it was systematically dismantled, its standards captured, and its commander brutally killed. This is the story of the Battle of Carrhae, a catastrophic clash born from Roman arrogance and Parthian genius.

The Ambition of a Triumvir

To understand Carrhae, one must first understand Marcus Licinius Crassus. As a member of the First Triumvirate alongside Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great, Crassus was arguably the richest man in Rome. His wealth was legendary, but his legacy was not. While Caesar was conquering Gaul and Pompey had already earned his “Great” moniker through victories in the East, Crassus’s military record was thin, consisting mainly of crushing the Spartacus slave revolt—a necessary but inglorious task.

Nearing his 60s, Crassus craved a military triumph to rival his partners and cement his place in Roman history. He set his sights on the Parthian Empire, a vast and wealthy civilization occupying modern-day Iran and Iraq. To the Romans, this seemed like a logical next step in their expansion. To Crassus, it was the key to ultimate glory. He amassed a formidable army of seven legions—nearly 40,000 heavy infantrymen, supported by cavalry and skirmishers—and in 55 BC, marched east, ignoring ill omens and the advice of the Senate.

A Fatal March into a Trap

Crassus’s first strategic blunder came before he even saw a Parthian soldier. King Artavasdes II of Armenia, a Roman ally, offered Crassus a safe route through his mountainous kingdom. This path would have provided supplies, additional troops, and, most importantly, rugged terrain that would have neutralized the Parthians’ greatest asset: their cavalry.

But Crassus was impatient. An Arab chieftain named Ariamnes, secretly in league with the Parthians, convinced him to take a direct route across the desert of northern Mesopotamia. He promised a weak and disorganized enemy, ripe for a swift, decisive victory. Trusting this treacherous guide, Crassus marched his legions off the banks of the Euphrates River and into the vast, featureless expanse. Ariamnes led the Romans on a grueling march, far from water sources, before finally slipping away and leaving them exhausted, thirsty, and perfectly positioned for the slaughter to come.

Surena’s Tactical Masterclass

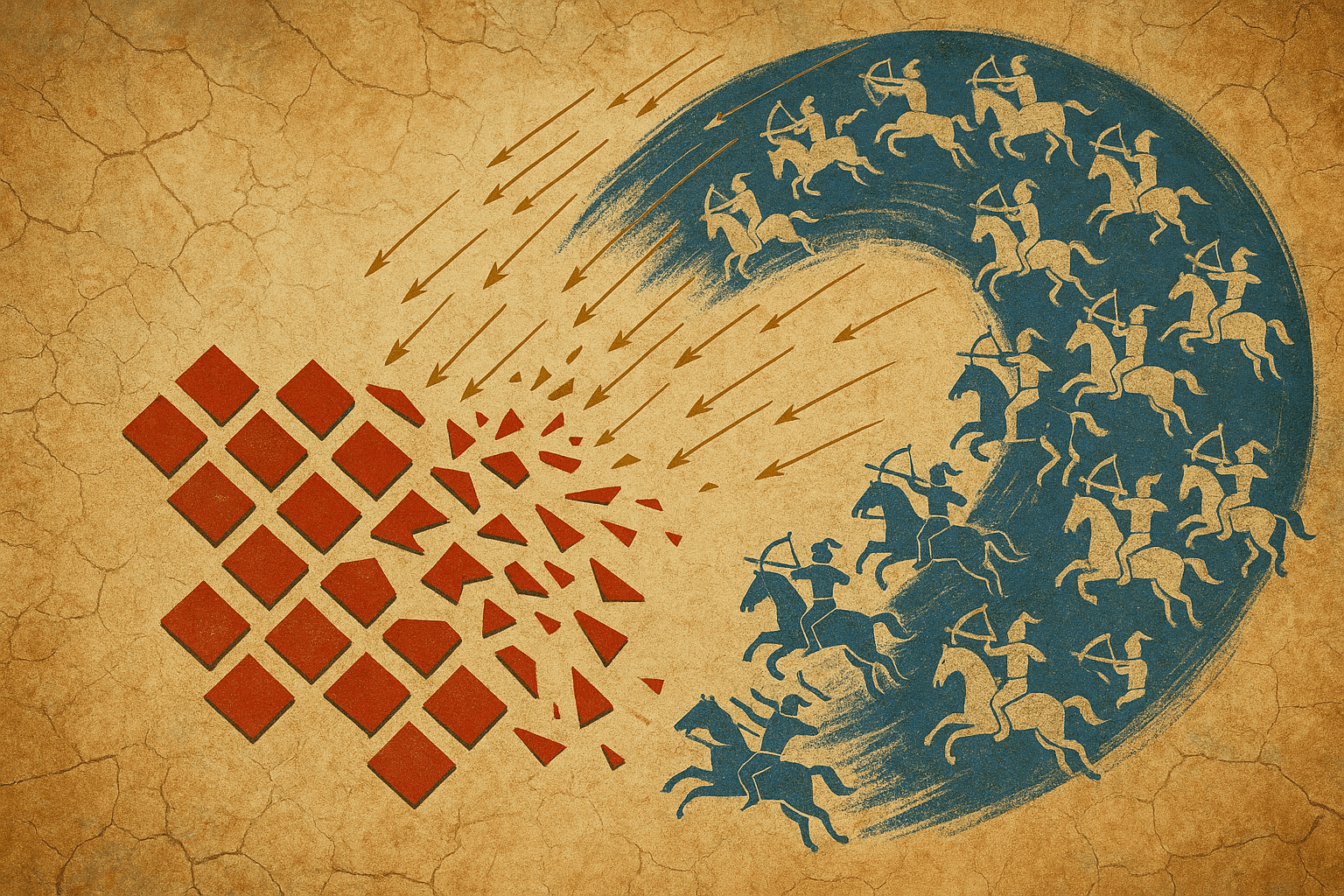

Awaiting the Romans was a Parthian army led by a brilliant young general named Surena. Though outnumbered nearly four to one, Surena’s force was composed of troops perfectly suited for the terrain.

- Horse Archers: 9,000 lightly armored but supremely mobile archers mounted on swift horses. They were masters of hit-and-run tactics, peppering the enemy with arrows from a distance.

- Cataphracts: 1,000 elite heavy cavalry. Both rider and horse were encased in iron scale armor, and they wielded a massive lance (the kontos) designed for shattering infantry formations.

When the Parthians appeared, Crassus, realizing he had been duped, hastily arranged his legions into a massive, hollow square. This defensive formation was designed to prevent being outflanked, but it also rendered his army a static, densely packed target. The battle he had prepared for—a clash of heavy infantry—was not the one Surena intended to fight.

A Storm of Arrows and a Son’s Sacrifice

The battle began not with a charge, but with a terrifying sound: the thunder of Parthian kettledrums, followed by a storm of arrows. The horse archers circled the Roman square, firing volley after volley. Their powerful composite bows fired arrows that pierced shields, pinned limbs, and punched through Roman armor. The Romans held their ground, believing the Parthians must eventually run out of ammunition.

p>

This was Surena’s first stroke of genius. He had organized a supply train of 1,000 camels laden with nothing but arrows. As one squadron of archers emptied their quivers, they would wheel back to a camel, re-supply, and return to the fray. The deadly barrage was endless.

Frustrated and seeing his men being whittled down, Crassus made a desperate move. He ordered his son, Publius Crassus—a promising young commander who had served with distinction under Caesar in Gaul—to lead a force of cavalry and infantry to drive the archers off. The Parthians, employing their signature tactic, feigned a retreat. Publius, smelling victory, pursued them eagerly, becoming separated from the main army. Once he was sufficiently isolated, the trap sprang. The “fleeing” horse archers turned, surrounding Publius’s detachment, while the terrifying cataphracts emerged from the dust to charge. The Roman force, exhausted and outmaneuvered, was annihilated. Publius, refusing to be captured, ordered one of his own men to kill him.

The morale of the main Roman army, already dented, was about to be shattered. The Parthians returned to the main battle, but this time they carried a gruesome trophy: the head of Publius, impaled on a spear, which they paraded just beyond the ranks of the horrified Roman soldiers. For Crassus, the sight of his son’s head was the final, soul-crushing blow. His command authority collapsed as he sank into a state of shock and grief.

The Humiliation and the Lost Eagles

The fighting continued until nightfall. The Romans had lost thousands, and thousands more were wounded. Under the cover of darkness, Crassus and the remnants of his army began a chaotic retreat toward the nearby Roman-garrisoned town of Carrhae, forced to abandon their wounded, whose cries haunted the departing soldiers.

The retreat was a prolonged nightmare of harassment and despair. Finally, pinned down and with his troops on the verge of mutiny, Crassus was forced to accept an invitation from Surena to parley for a truce. It was another trap. During the supposed negotiations, a scuffle broke out, and Crassus was killed. One lurid account, likely propaganda, claims the Parthians poured molten gold down his throat—a macabre commentary on his insatiable greed.

For Rome, the loss of life and the death of Crassus were secondary to the ultimate humiliation: the capture of the legionary standards, the silver eagles known as aquilae. To lose an eagle was the greatest shame a legion could suffer, a symbol of its utter defeat and dishonor. The aquilae of Carrhae would become a national obsession, a stain on Roman pride that would not be cleansed for decades.

The Lasting Legacy of Carrhae

The Battle of Carrhae was a disaster of epic proportions. An estimated 20,000 Romans were killed and another 10,000 were captured, many of whom were reportedly settled on the far eastern frontier of the Parthian Empire. The defeat had immediate political consequences, as Crassus’s death removed the buffer between Caesar and Pompey, accelerating their collision course toward civil war.

Militarily, Carrhae established the Euphrates River as the durable boundary between the two great powers for centuries. It taught Rome a bitter lesson: that its legions were not invincible and that tactics had to be adapted for new enemies and new environments. The lost eagles became a rallying cry, their eventual diplomatic recovery by Emperor Augustus decades later celebrated as a victory equal to a battlefield triumph. Carrhae remains a timeless and bloody testament to the dangers of hubris and a chilling reminder that, in the desert, glory can turn to dust in an instant.