The Scale of a Man-Made Sea

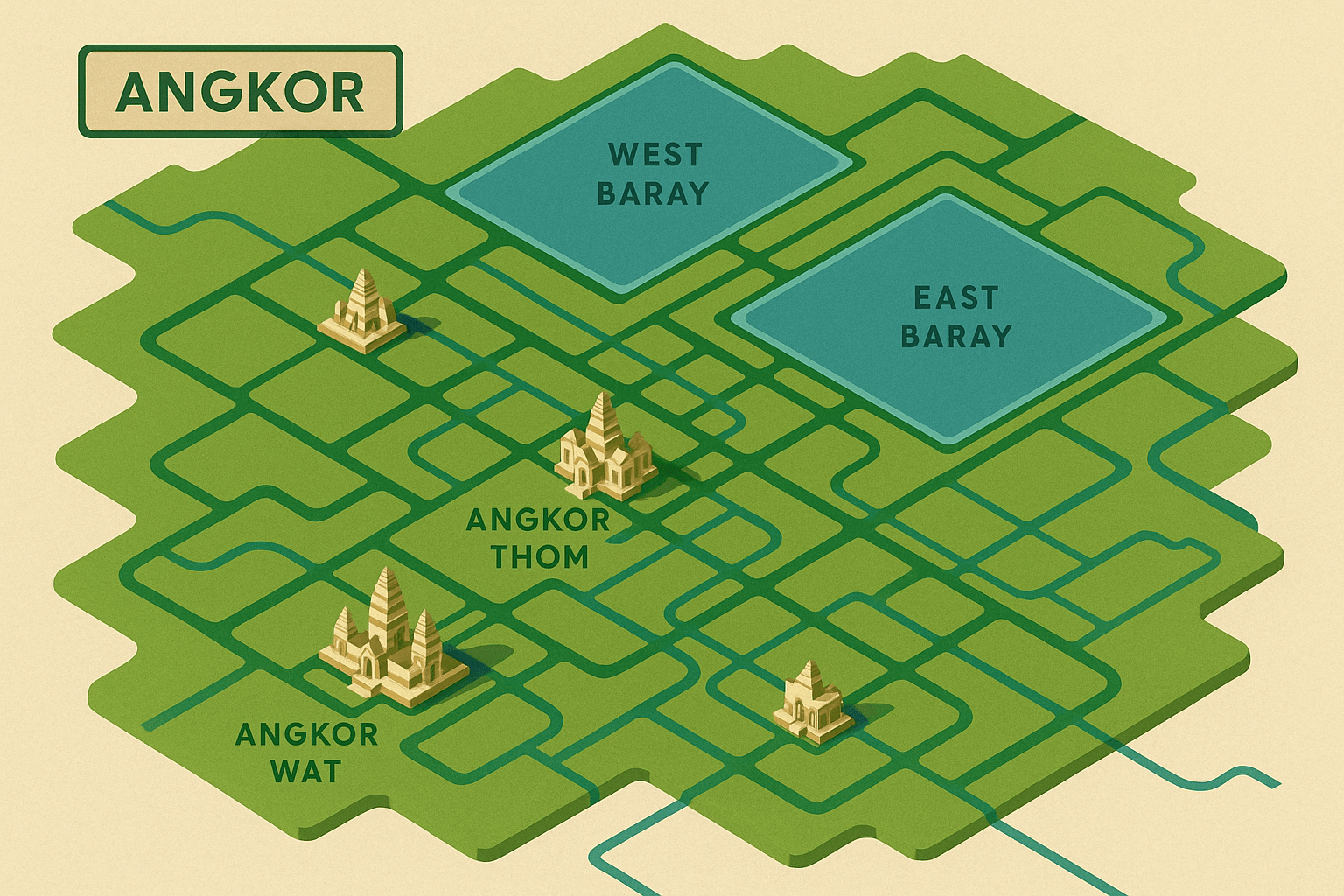

To call a baray a reservoir is an understatement. These were, for all intents and purposes, inland seas excavated by human hands. The two most famous are the East Baray and the West Baray, which once flanked the main urban core of Angkor Thom. While the East Baray is now dry and visible as a massive rectangle of rice paddies, the West Baray still holds water, giving us a breathtaking sense of their original scale.

How big were they? The West Baray measures a staggering 8 kilometers long by 2.1 kilometers wide (about 5 miles by 1.3 miles). Its construction involved moving millions of cubic meters of earth to create enormous dikes, a feat requiring an immense, coordinated labor force. When full, it held over 50 million cubic meters of water. This wasn’t just a pond; it was a defining feature of the landscape, engineered to capture the life-giving monsoon rains that inundated the region for half the year.

The Agricultural Engine of an Empire

The primary purpose of this monumental system was brilliantly practical: to conquer the seasonal nature of a monsoon climate. Cambodia experiences a distinct wet season, with torrential downpours, followed by a long, arid dry season. For a civilization dependent on rice, this created a boom-and-bust cycle.

The Angkorian engineers devised a solution. A complex network of canals and channels diverted water from rivers, like the Siem Reap River, and captured a massive volume of runoff during the wet season, storing it in the barays. By subtly sloping the entire network, they created a massive, gravity-fed irrigation system. Using a series of sluice gates and dikes, they could precisely release this stored water during the dry season to irrigate endless fields of rice.

The results were transformative:

- Multiple Harvests: Instead of a single rice harvest per year, this system enabled up to three. This agricultural surplus was the economic bedrock of the empire.

- Population Support: This abundance of food supported a massive population. Estimates suggest that in the 13th century, the greater Angkor region was home to between 750,000 and one million people, making it the largest pre-industrial urban complex in the world.

- Fuel for Ambition: The surplus fed the vast armies that expanded Khmer influence, the legions of laborers who built the temples, and the priestly class that maintained them. Without the barays, the glorious temples we see today could never have been built.

A Cosmos Rendered in Water and Stone

But the barays were far more than just utilitarian infrastructure. For the Khmer, engineering and spirituality were inseparable. Their worldview was shaped by Hindu and Buddhist cosmology, which envisioned the universe with a central, sacred peak, Mount Meru, surrounded by a great cosmic ocean. The kings of Angkor sought to replicate this divine geography on Earth.

In this terrestrial cosmos, the great temple-mountains like Angkor Wat, the Bakheng, or the Baphuon represented Mount Meru, the home of the gods. The vast, shimmering barays surrounding them were designed to be earthly representations of the mythological Sea of Milk, the cosmic ocean itself. The moats that surround individual temples were smaller-scale versions of the same concept.

This was the ultimate expression of the king’s power as a devaraja, or “god-king.” By building these structures, he was not just managing resources; he was harmonizing his kingdom with the heavens, ensuring divine favor, stability, and prosperity for his people. To further sanctify these waters, temples known as mebons (like the East Mebon and West Mebon) were constructed on artificial islands in the very center of the barays. From the shore, they would have appeared to float magically on the surface of the man-made sea—a direct link between the human world and the divine realm.

A Fragile Legacy

For centuries, this intricate system was the source of Angkor’s strength. But its sheer complexity may have also contributed to its eventual decline. The system required constant, centralized maintenance. As the empire faced external pressures from rival kingdoms and a potential shift in religious focus, the ability to command the massive labor needed for upkeep may have waned.

More critically, the system was optimized for a stable climate. Recent studies suggest that the 14th and 15th centuries saw intense climate variability, with periods of prolonged, severe drought followed by torrential mega-monsoons. The droughts would have rendered the system useless, while the subsequent floods could have overwhelmed the network, destroying canals and dikes and causing catastrophic damage. A system built for stability proved too brittle to handle radical change.

Today, as you fly into Siem Reap, you can still trace the ghost-like outlines of the ancient barays and canals from the air. Modern technologies like LiDAR have revealed the full, astonishing extent of this hydraulic city. They stand as a silent testament not just to the temples they supported, but to the engineering genius and cosmic ambition of the Khmer Empire. They remind us that the greatest civilizations are often built not on stone, but on their ability to master the most essential element of all: water.