Ask anyone about the Antikythera shipwreck, and they’ll likely mention one thing: the Mechanism. And for good reason. The world’s first known analog computer is a mind-boggling piece of ancient genius that has rightly dominated headlines and academic papers for decades. But to focus solely on the Mechanism is to miss the forest for one extraordinary, gear-filled tree. The same Roman-era vessel that carried this astronomical calculator to its watery grave was also laden with a breathtaking collection of art and luxury goods—a time capsule of the high-stakes art market of the 1st century BCE.

Sometime around 65 BCE, a massive Roman cargo ship, heavy with the treasures of the Greek world, foundered in a storm off the treacherous coast of the Greek island of Antikythera. There its cargo lay, scattered across the seabed for two millennia until sponge divers stumbled upon it in 1900. What they, and subsequent archaeological expeditions, have brought to the surface is a stunning snapshot of what a wealthy Roman patron would have paid a king’s ransom to display in their lavish villa or a public square.

A King’s Ransom in Bronze

Perhaps the most significant treasures beyond the Mechanism are the bronze statues. In the ancient world, large-scale bronze sculptures were far more common and prized than marble ones. However, their intrinsic value became their curse; over the centuries, the vast majority were melted down to be repurposed for coins, cannons, or other objects. Finding an original Greek bronze is exceptionally rare. The Antikythera shipwreck, by sinking its cargo, accidentally created one of the world’s most important museums of ancient bronze.

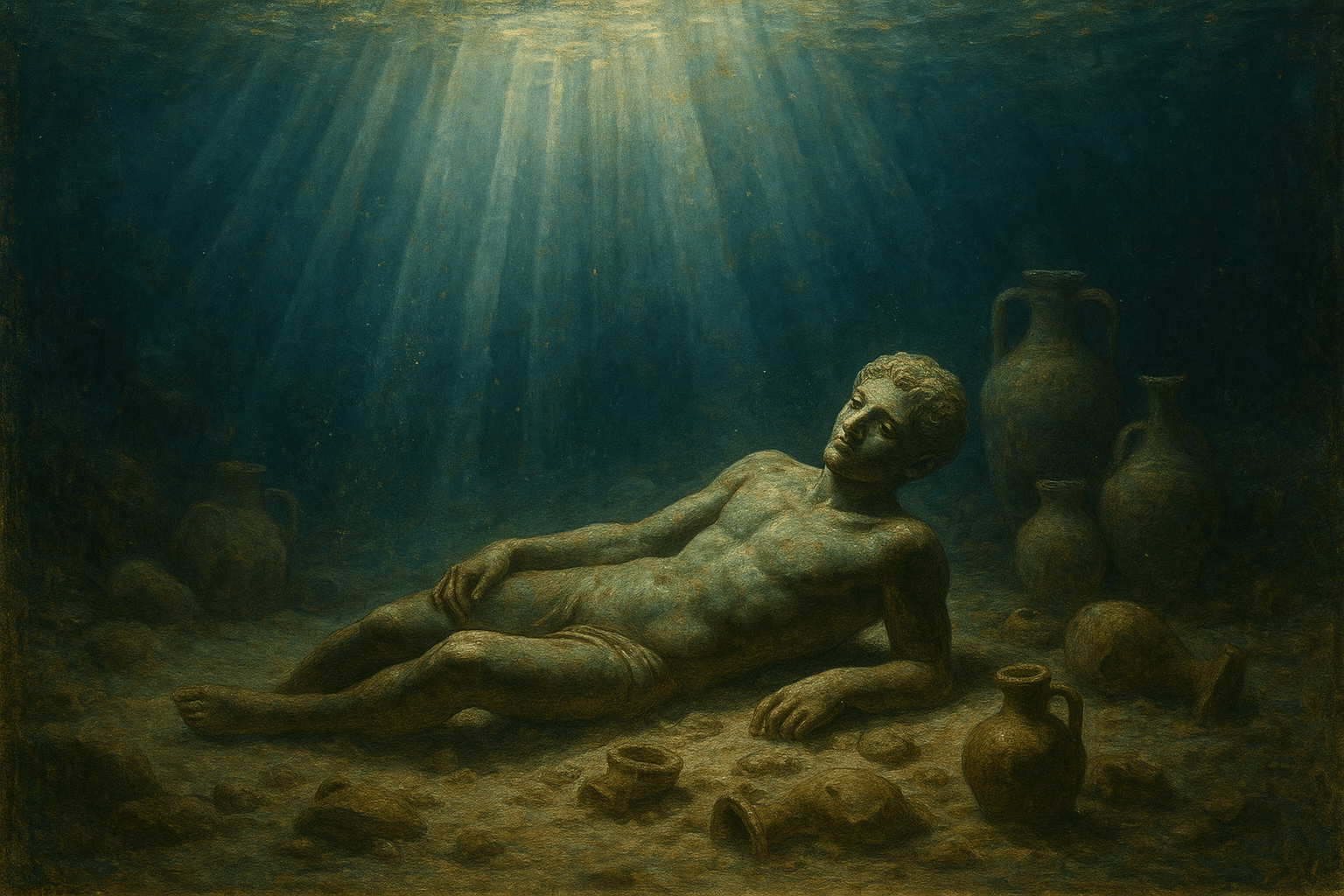

The star of this collection is the magnificent Antikythera Youth, also known as the Antikythera Ephebe. This larger-than-life-size statue of a young man, recovered in pieces, has been painstakingly restored to its former glory. His athletic form, captured in a relaxed pose with his right arm outstretched, is a masterpiece of 4th-century BCE style. Scholars debate his identity: is he the Trojan prince Paris holding the Apple of Discord, or perhaps the hero Heracles holding the apples of the Hesperides? Regardless of his name, he represents the pinnacle of classical Greek sculpture, an original work by a master that would have otherwise been lost forever.

Equally compelling is the haunting portrait head known as the Antikythera Philosopher. Unlike the idealized Youth, this is a work of striking realism, a hallmark of the Hellenistic period. With a furrowed brow, a dense beard, and an intense gaze (which would have originally held inlaid eyes), the sculpture captures the specific character and intellectual weight of an individual. He is not a generic wise man, but a specific person whose thoughts seem to simmer just beneath the bronze surface. He is one of the very few such portraits to survive from antiquity.

These were not the only bronzes. Divers have recovered a trove of dismembered limbs—arms, feet, and hands—as well as fragments of horses, all hinting at a much larger group of statues that remain buried or were shattered on impact. Recent expeditions have even found a new bronze arm, confirming that the seabed still has secrets to yield.

Marble Masterpieces Carved for Rome

Alongside the priceless bronzes lay a substantial cargo of marble statues. While more have survived on land than their bronze counterparts, the Antikythera marbles showcase the sheer scale and quality of the art being trafficked to Italy. The most imposing of these is a colossal, over-life-sized marble statue of Herakles. Though heavily worn by the sea, its immense scale and powerful musculature are undeniable. It is a variant of a famous sculptural type attributed to the master sculptor Lysippos, a design incredibly popular with Roman collectors who admired Herakles’ association with strength and divine perseverance.

The ship was a veritable floating art gallery. Other marble figures included a statue of Odysseus, poised to attack, and more idealized god-like figures, all destined to adorn the gardens and galleries of a Roman aristocrat. They demonstrate the dual nature of Roman taste: a desire for famous Greek originals (the bronzes) and an appetite for high-quality, impressive copies and adaptations of well-known masterpieces (the marbles).

The Glitter of Everyday Luxury

It wasn’t just monumental sculpture that filled the ship’s hold. The wreck has given us a dazzling glimpse into the wider array of luxury goods that defined elite Roman life. Among the most beautiful finds are the perfectly preserved glass vessels.

Imagine unwrapping a 2,100-year-old package to find delicate bowls and goblets made of stunningly colored glass. The Antikythera divers found just that. The best examples are intricate millefiori (“a thousand flowers”) bowls, created by fusing together rods of multi-colored glass to create vibrant, mosaic-like patterns. This was Roman-era Murano glass—incredibly difficult to produce, breathtakingly beautiful, and a clear signal of immense wealth and sophisticated taste. These weren’t for daily use; they were showpieces meant to dazzle dinner guests.

The ship also carried fine pottery, amphorae for transporting wine from Rhodes and Ephesus, and even the remnants of ornate furniture. One of the most intriguing finds was a heavily corroded object that, upon analysis, was revealed to be a decorative bronze throne or couch, inlaid with decorative motifs. There were even personal effects, such as gold jewelry and the skeletal remains of at least four individuals—a somber reminder of the human tragedy behind this archaeological treasure.

What the Cargo Tells Us

Taken together, the Antikythera treasures paint a vivid picture of the 1st century BCE. This was a period of immense change, as the Roman Republic was extending its power across the Mediterranean. Immensely wealthy generals, governors, and merchants, enriched by conquest, were building palatial homes in and around Rome and filling them with the cultural patrimony of the Greek world they now dominated.

The Antikythera ship was a key part of this supply chain. It was likely sailing from a major Eastern Mediterranean port like Ephesus or Pergamon, loaded with both plundered originals and newly commissioned works, all heading west to a booming Roman art market. The wreck provides concrete evidence for what ancient writers like Pliny and Cicero describe: a Roman obsession with Greek art and a highly organized trade to satisfy it. It is, in effect, a single, perfectly preserved transaction from the ancient world’s most important art market.

So while the Antikythera Mechanism continues to rewrite the history of science, let’s not forget the rest of its cargo. The statues, glassware, and other luxuries are not merely beautiful objects. They are witnesses to history, revealing the tastes, ambitions, and globalized economy of the ancient world in stunning, sea-worn detail.