The Seeds of Chaos: A Sinking Ship and a Broken Oath

The story begins with a disaster at sea. In 1120, King Henry I of England, a formidable and effective ruler, lost his only legitimate son and heir, William Adelin, in the tragic sinking of the White Ship. Faced with a succession crisis, Henry did something unprecedented: he made his barons swear an oath to accept his daughter, Matilda, as their future ruler.

Matilda was no ordinary princess. The widow of the Holy Roman Emperor (hence her title, “Empress”), she was intelligent, proud, and accustomed to wielding power. But the idea of a ruling queen was alien and deeply unsettling to the Norman aristocracy. A woman’s role was to marry and produce heirs, not to command armies and dispense justice.

When King Henry I died in 1135, the oaths sworn to Matilda proved as fragile as a winter frost. While Matilda was in Anjou with her second husband, Geoffrey Plantagenet, her cousin, Stephen of Blois, acted with lightning speed. He was the son of Henry I’s sister, making him the king’s favorite nephew. He was popular, charming, and crucially, he was male. He raced to England, secured the support of London and the church—aided by his own brother, Henry of Blois, the powerful Bishop of Winchester—and had himself crowned king. The kingdom’s great barons, who had sworn fealty to Matilda, quickly fell in line behind a king who was present, crowned, and a man.

A Kingdom Divided

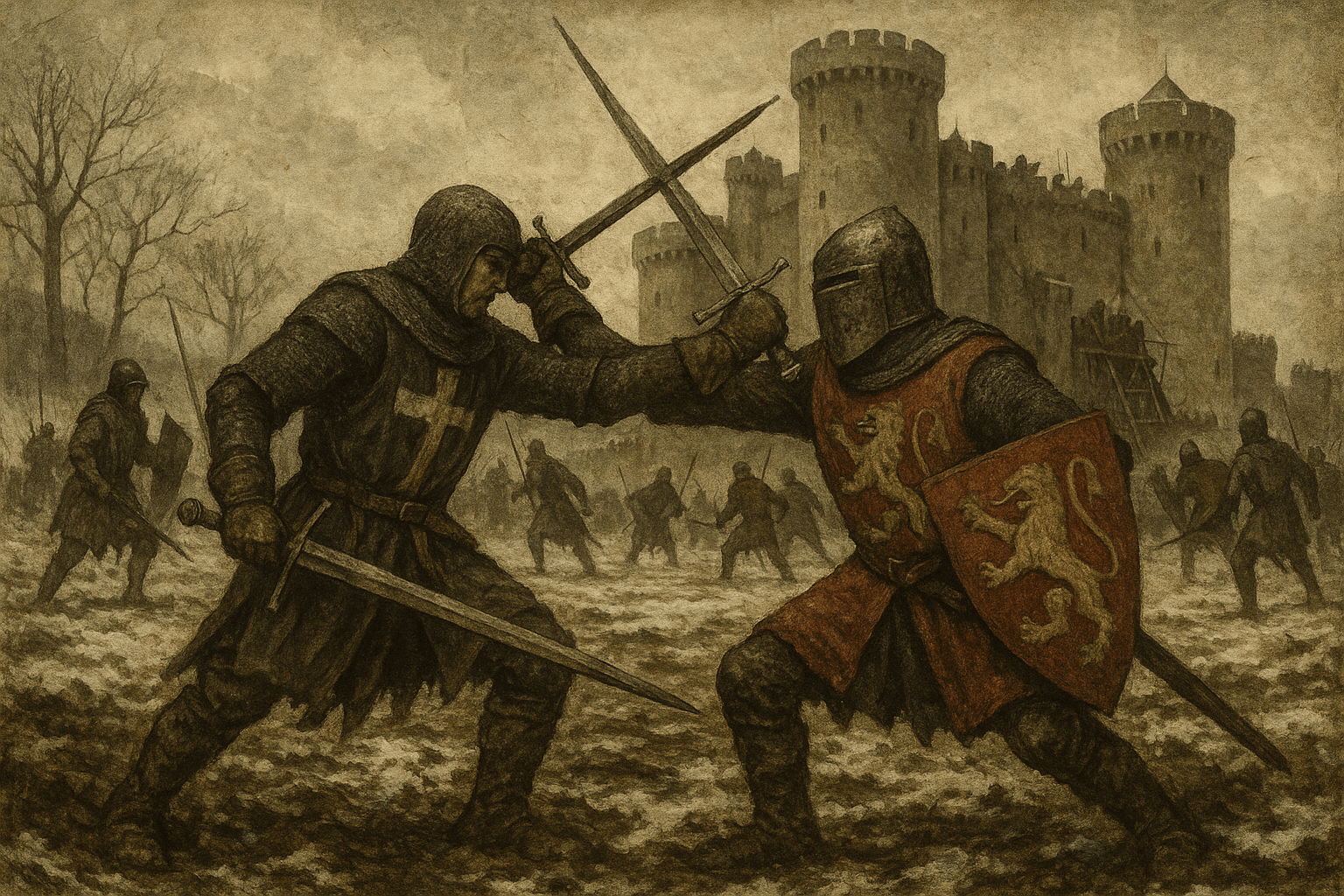

Matilda, however, was not one to be cast aside. Supported by her powerful illegitimate half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, she prepared for war. In 1139, she landed in England, and the conflict ignited in earnest. England split into factions. The southwest largely supported Matilda, while London and the southeast remained loyal to Stephen. What followed was not a war of grand, decisive battles, but a grueling campaign of sieges, raids, and shifting allegiances.

The country began to disintegrate. Royal authority, which Henry I had painstakingly built, crumbled. Local lords took matters into their own hands, becoming warlords in their own right. They built unlicensed castles, known as “adulterine” castles, from which they terrorized the countryside, extorted taxes from local villages, and fought private wars with their rivals.

“They Hanged Them Up by the Feet”

It is from this period that we get the most harrowing descriptions of daily life. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle provides a terrifying account of the suffering of the common people:

“They filled the towns with castles… they greatly oppressed the wretched people of the land with this castle-work… they took those they believed to have any goods, both by day and by night, men and women, and put them in prison for their gold and silver, and tortured them with indescribable tortures… They hanged them up by the feet and smoked them with foul smoke… They put knotted strings about their heads and twisted them until it went to the brain.”

Famine followed the violence. Fields went unplowed as farmers fled the terror. The chronicler concludes that “it was said openly that Christ and his saints slept.” For the average person, the fight for the crown was a distant affair; the real horror was the complete breakdown of society at the hands of petty tyrants.

The Shifting Tides of War

The war ebbed and flowed, with neither side able to land a killing blow. The fortunes of the two claimants rose and fell with dramatic speed.

- The Capture of a King (1141): At the Battle of Lincoln, Matilda’s forces, led by Robert of Gloucester, won a stunning victory. King Stephen himself was captured and imprisoned. It seemed Matilda had won.

- The Arrogance of an Empress (1141): Matilda marched to London to be crowned. But her haughty demeanor and immediate demands for taxes alienated the citizens who had previously supported Stephen. Before her coronation could take place, the Londoners revolted, forcing her to flee the city in a humiliating retreat. It was her greatest blunder.

- The Prisoner Exchange (1141): Later that year, Matilda’s forces were defeated at the Rout of Winchester. Her rock, Robert of Gloucester, was captured. With both sides holding a prize captive, a stalemate was reached. The only logical solution was an exchange: Stephen for Robert. The king was freed, and the war was back on.

The Rise of a New Generation

The conflict dragged on for years, a grinding war of attrition that exhausted the kingdom. Robert of Gloucester died in 1147, and a disheartened Matilda left England the following year, leaving the fight to her son. That son was Henry FitzEmpress, a young man who possessed his grandfather’s energy and his mother’s ambition, but with a far better grasp of politics.

As Henry grew into a formidable warrior and leader, he took over the Angevin cause. He campaigned in England, proving himself a more capable military commander than Stephen had ever been. The final turning point came not on the battlefield, but through personal tragedy. In 1153, Stephen’s beloved son and heir, Eustace, died suddenly. Heartbroken and weary of war, Stephen lost the will to continue the fight for his dynasty.

With a new, dynamic claimant on one side and an aging, grief-stricken king on the other, the barons of England finally forced a peace. The Treaty of Wallingford (also known as the Treaty of Winchester) was agreed upon in late 1153. The terms were simple and pragmatic:

- Stephen would remain king for the rest of his life.

- Stephen officially recognized Matilda’s son, Henry, as his heir.

- Stephen’s remaining son, William, would do homage to Henry in exchange for keeping his family’s lands.

The Anarchy was over. Stephen died less than a year later, in October 1154. Henry FitzEmpress peacefully ascended the throne as King Henry II, the first of the great Plantagenet kings. His first task was to tear down the adulterine castles and restore the king’s law to a land that had known only chaos for nearly two decades. The saints, it seemed, had finally awoken.