The Perfect Storm: Reformation and Radicalism

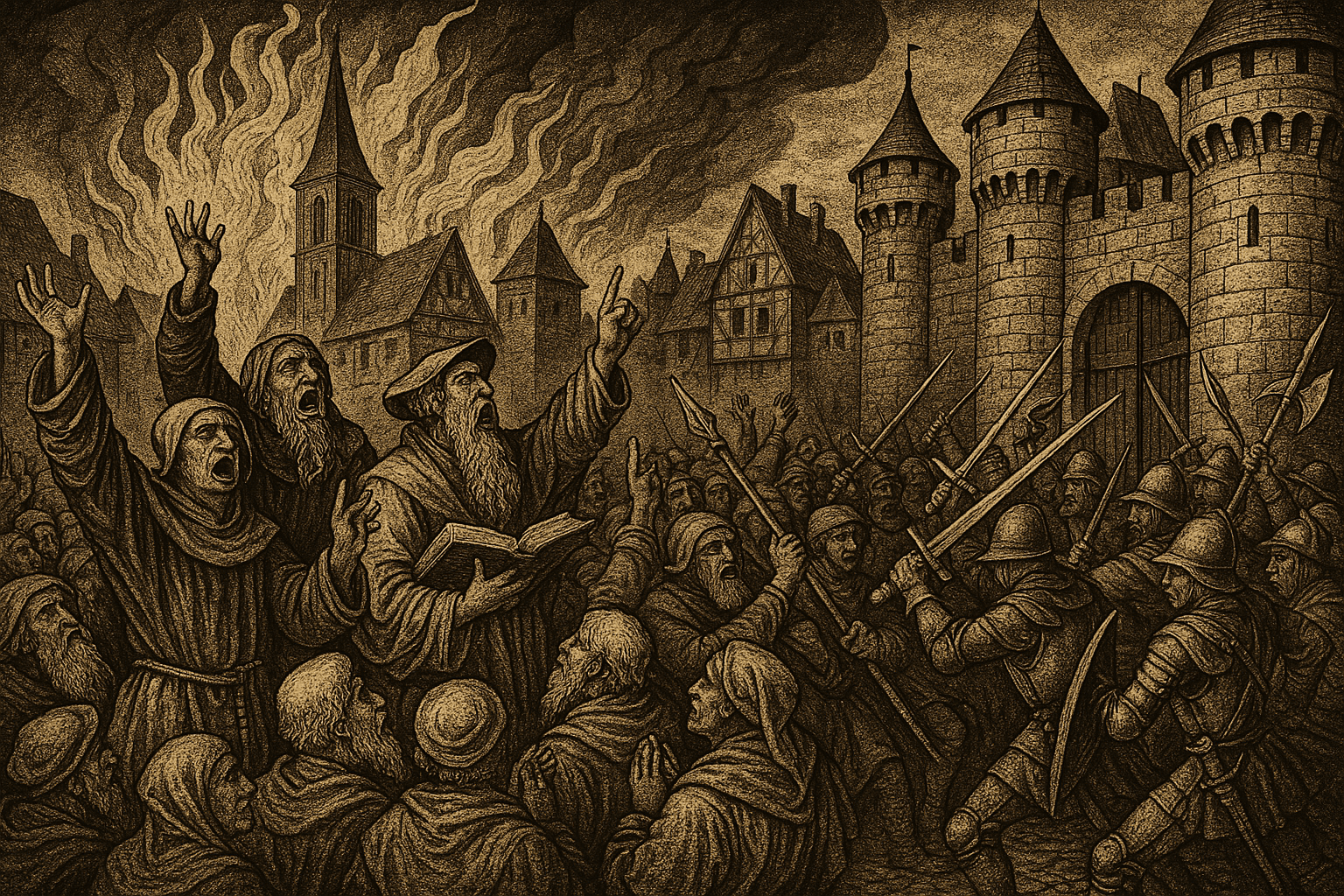

To understand Münster, we must first look at the turbulent world of the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther had shattered the unity of Western Christendom, and his challenge to papal authority opened the floodgates for new, often radical, interpretations of the Bible. Among the most controversial of these new groups were the Anabaptists.

Their name, meaning “re-baptizers”, came from their most fundamental belief: that baptism was a conscious declaration of faith that only an adult could make. This wasn’t just a theological quibble; it was a direct challenge to the very structure of society. Infant baptism bound a person to the state-sanctioned church from birth. To reject it was to reject the authority of both princes and priests. Unsurprisingly, Anabaptists were brutally persecuted across Europe by both Catholics and mainstream Protestants.

This constant persecution radicalized a faction of the movement. Apocalyptic preachers like Melchior Hoffman prophesied that the Second Coming of Christ was imminent and that God would establish a “New Jerusalem” on Earth to protect the faithful from the coming judgment. Initially, this holy city was prophesied to be Strasbourg. But the prophecies of a charismatic Dutch baker named Jan Matthys would soon point to a new destination: the wealthy city of Münster.

Seizing the City of God

Münster was ripe for revolution. Its citizens were already in conflict with their ruling Prince-Bishop, Franz von Waldeck, and a popular local preacher named Bernhard Rothmann had begun to embrace Anabaptist ideas. Word spread like wildfire: Münster was the chosen city. Anabaptists from across the Netherlands and Germany began to flock there.

In February 1534, the situation reached a tipping point. In a stunning turn of events, the Anabaptists won control of the city council through elections, solidifying their power. The old order collapsed. Catholics and Lutherans who refused to convert were expelled, and the Prince-Bishop, now locked out of his own capital, gathered an army and laid siege to the city.

Inside the walls, Jan Matthys took charge. The transformation of Münster into the New Jerusalem began immediately and violently.

- Forced Baptism: All remaining citizens were given a stark choice: be re-baptized as an Anabaptist or face expulsion or death.

- Iconoclasm and Book Burning: In a frenzy of puritanical zeal, followers smashed statues, burned paintings, and destroyed church organs. All books except the Bible were tossed onto massive bonfires.

- Abolition of Private Property: A radical form of Christian communism was instituted. All money was outlawed, and citizens were forced to hand over all their gold, silver, and private possessions to a common storehouse. Doors were to be kept unlocked at all times.

Matthys ruled as an absolute prophet, but his reign was cut short by his own apocalyptic hubris. On Easter Sunday 1534, believing he was a new Gideon who God would divinely protect, he rode out with a handful of followers to break the siege. He was immediately cut down by the Bishop’s troops, his body dismembered, and his head stuck on a pike for the city to see.

King Jan and the Reign of Polygamy

With the prophet dead, a power vacuum threatened to tear the city apart. Into this void stepped Matthys’s charismatic and theatrical disciple, a 25-year-old tailor named Jan van Leiden (John of Leiden).

Jan van Leiden was a master of political theater. He dissolved the city council and, claiming a direct revelation from God, had himself crowned King of the New Jerusalem. He fashioned a throne, royal robes, and a golden crown, establishing a lavish court that stood in stark contrast to the famine beginning to grip the city’s populace. But his most infamous and socially destructive decree was yet to come: the institution of polygamy.

Citing the precedent of Old Testament patriarchs and a practical problem—the city had three times as many women as men—Jan made polygamy compulsory. Any unmarried woman of a certain age was forced to take a husband. Refusal was a capital crime. While presented as a divine commandment, it was a system of institutionalized sexual slavery designed to satisfy the lust of the male leadership and exert total control. Jan himself led by example, eventually taking sixteen wives, including the beautiful young widow of Jan Matthys. The social fabric of Münster frayed. Women who resisted were punished, and one, Elisabeth Wandscherer, was publicly beheaded by King Jan himself for “insubordination.”

The Brutal End and a Grisly Warning

Outside the walls, the Prince-Bishop’s siege tightened its grip. Inside, starvation, disease, and terror reigned. The utopian dream had become a desperate, cannibalistic hellscape. The end was inevitable.

On the night of June 25, 1535, two deserters who had escaped the city showed the Bishop’s forces a weak point in the walls. The soldiers stormed Münster, and a night of horrific slaughter ensued. Men, women, and children were massacred in the streets. King Jan and his top lieutenants were captured alive.

Their fate was to be a terrifying deterrent. For six months, Jan van Leiden, Bernhard Knipperdolling, and Bernhard Krechting were paraded around the region as monstrous curiosities. In January 1536, they were brought back to Münster’s central market square. There, before a hushed crowd, they were tied to a post. For the better part of an hour, their flesh was ripped from their bodies with red-hot tongs. Finally, they were dispatched with daggers to the heart.

But even that was not the end. Their bodies were placed into three iron cages, which were then hoisted to the top of the steeple of St. Lambert’s Church, left to rot as a permanent warning against rebellion and heresy. Incredibly, those same three cages hang there to this day—empty reminders of the apocalyptic madness that once consumed the city.

The Münster Rebellion cast a long, dark shadow. For centuries, it was used as propaganda to demonize all Anabaptists, branding even peaceful, non-violent communities like the Mennonites and Amish with the stigma of radicalism and violence. It remains one of history’s most potent and chilling cautionary tales, a stark reminder of how quickly the fervent pursuit of heaven on earth can create a living hell.