Imagine yourself in a bustling 14th-century English town. The air is thick with the smell of woodsmoke, livestock, and damp earth. You step into a crowded alehouse, seeking refuge and refreshment. The drink of choice isn’t water—a notoriously risky proposition—but a cloudy, nutritious pint of ale. But how do you know it’s good? How do you know it hasn’t been watered down, brewed with tainted grain, or sold at an extortionate price? You don’t have to worry. That’s the job of the Ale-Conner.

In the intricate tapestry of medieval society, few roles were as vital to the everyday person, yet as overlooked by modern history, as that of the Ale-Conner. These were the official beer inspectors of their day, tasked with a mission that was part consumer protection, part public health, and part economic regulation.

Who Were the Ale-Conners?

The name itself offers a clue. “Conner” derives from the Old English word cunnan, which means “to test” or “to know.” An Ale-Conner was, quite literally, an “ale-knower.” Appointed or elected by the local manor court or town council, these individuals were empowered to uphold the quality, measure, and price of ale sold within their jurisdiction.

This wasn’t some informal honor. In cities like London, the Ale-Conners were sworn officials who took an oath to perform their duties “well and truly.” Their job was to protect the public from the misdeeds of unscrupulous brewers and taverners. In a world without modern regulatory bodies, they were the first and last line of defense for the common drinker.

“Liquid Bread”: Why Ale Mattered So Much

To understand the Ale-Conner’s importance, we must first grasp the central role of ale in medieval life. It was far more than a simple alcoholic beverage; it was a fundamental pillar of the daily diet.

- A Source of Nutrition: Ale was thick, unfiltered, and packed with calories from the grain. It was often called “liquid bread” and provided a crucial energy source for laborers and peasants whose diets were otherwise sparse.

- Safer than Water: With sanitation being rudimentary at best, local water sources like wells and rivers were often contaminated with human and animal waste, making them breeding grounds for diseases like dysentery and cholera. The brewing process, which involved boiling the water, killed off most harmful pathogens, making ale a much safer and healthier option.

- Consumed by All: Men, women, and even children drank ale regularly. Weaker, low-alcohol versions known as “small beer” were common breakfast drinks, providing hydration and calories to start the day.

Brewing was predominantly a domestic task, often performed by women known as “alewives” or “brewsters.” They brewed for their own families and often sold the surplus to neighbors, making it a vital source of household income. As towns grew, commercial alehouses became more common, and with them, the temptation to cut corners for profit.

The Ale-Conner’s Duties

An Ale-Conner’s visit was a serious event for any brewer or publican. Their inspection covered three critical areas:

- Quality: The conner would taste the ale to judge its flavor, strength, and wholesomeness. Was it made from good quality malt? Was it “ropey”, “sour”, or otherwise undrinkable? Bad ale could not only taste foul but also make people sick, and it was the conner’s job to ensure it never reached the public.

- Price: The price of ale was not left to the free market. It was regulated by a statute known as the “Assize of Bread and Ale”, first codified in the 13th century. This law linked the price of a gallon of ale directly to the price of the grain used to make it. The Ale-Conner’s job was to know the current price of barley, malt, and oats and ensure brewers were charging a fair, legal price.

- Measure: The conner also checked the drinking vessels. They made sure that a “pint” was truly a pint and that customers weren’t being short-changed with undersized mugs or jugs. Fraudulent measures were confiscated and destroyed.

Those who failed the inspection faced swift justice. Punishments ranged from fines to public humiliation. A brewer found guilty of selling bad ale might be forced to drink a large quantity of their own foul brew before having the rest poured over their head, or they could be placed in the stocks or a dunking stool for all the town to see.

The Legend of the Leather Breeches

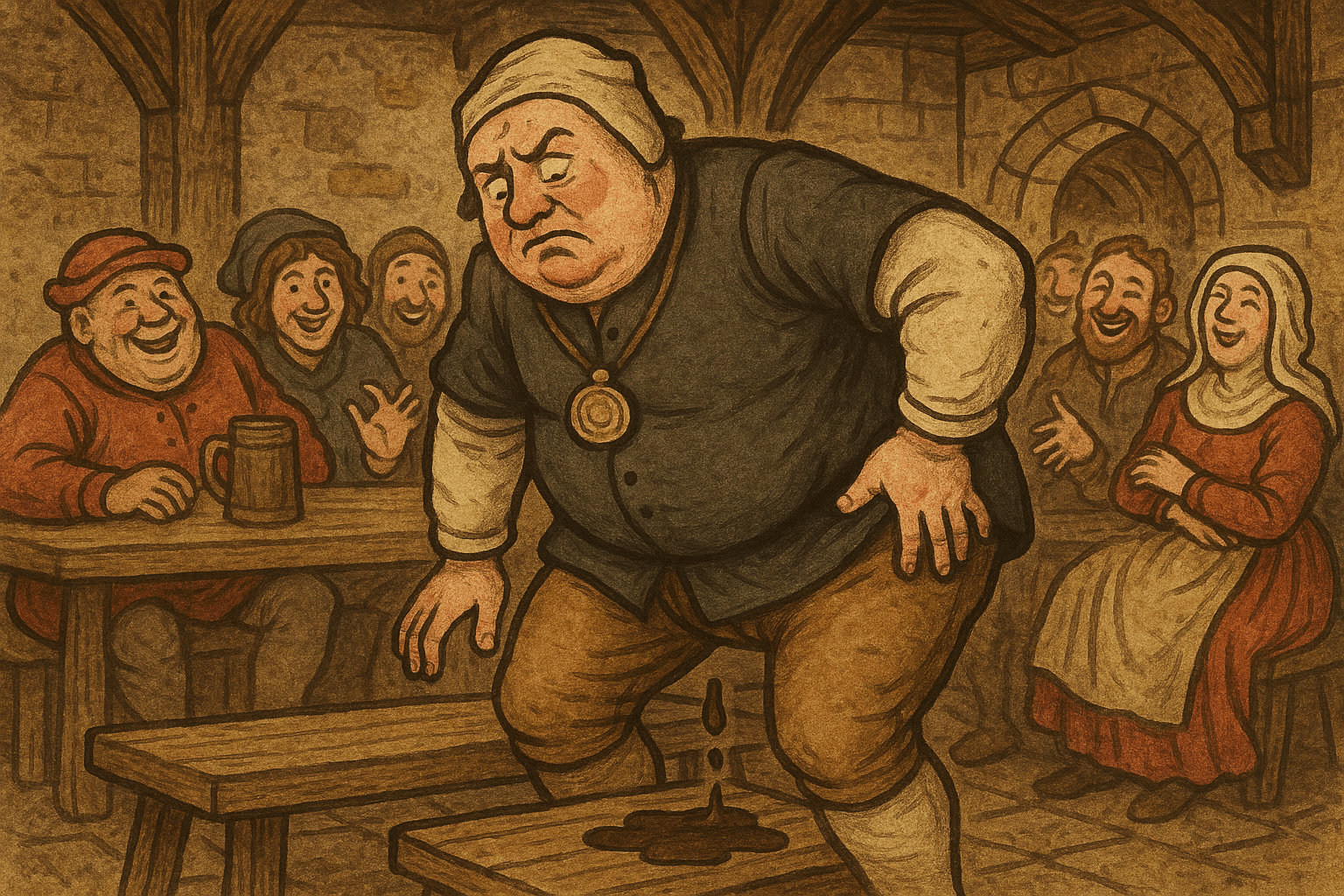

No discussion of the Ale-Conner is complete without mentioning their most famous, if likely apocryphal, testing method. The story goes that to test the quality of an ale, the conner would employ a very personal, hands-on (or rather, bottoms-on) technique.

The Ale-Conner, clad in sturdy leather breeches, would stride into the alehouse and splash a sample of the new brew onto a wooden bench. He would then sit squarely in the puddle and proceed to drink his pint, waiting for about half an hour. The final judgment came when he stood up.

If his leather breeches stuck firmly to the bench, the ale passed the test! The theory was that a well-brewed ale would contain a certain amount of residual sugars from the malt. As the ale warmed and evaporated under the conner’s body heat, these sugars would create a sticky residue. If the breeches didn’t stick, it suggested the ale was weak, watery, and lacking in proper ingredients.

It’s a fantastic image, but did it actually happen? Almost certainly not. Historians have found no primary source evidence describing this specific practice. It’s more likely a piece of folklore that cleverly illustrates the principle of their work: ensuring the beer had substance. The Ale-Conner’s real methods were the more mundane, but no less effective, tools of the trade: a discerning palate, a keen nose, and a sharp eye.

The Decline of a Profession

For centuries, the Ale-Conner remained a respected and essential figure in English towns. But as the medieval world gave way to the early modern period, their role began to fade.

The rise of large-scale commercial breweries using hops (which acted as a preservative and standardized flavor) began to replace small-scale alewives. Scientific advancements, like the invention of the hydrometer in the 18th century, provided a much more precise way to measure the alcoholic strength and sugar content of beer, making the subjective “taste test” obsolete.

While the functional role of the Ale-Conner disappeared, the title itself has survived in a few places as a cherished ceremonial tradition. The City of London Corporation, for example, still appoints four Ale Conners annually, who take an oath and perform symbolic “tastings” at local pubs, connecting the present day to a long and thirsty history.

So, the next time you enjoy a carefully crafted pint, spare a thought for the forgotten Ale-Conner. They were the original guardians of good beer—consumer advocates who ensured every mug was wholesome, every price was fair, and every measure was true. In their own way, they helped keep the social fabric of medieval England from coming unstuck.