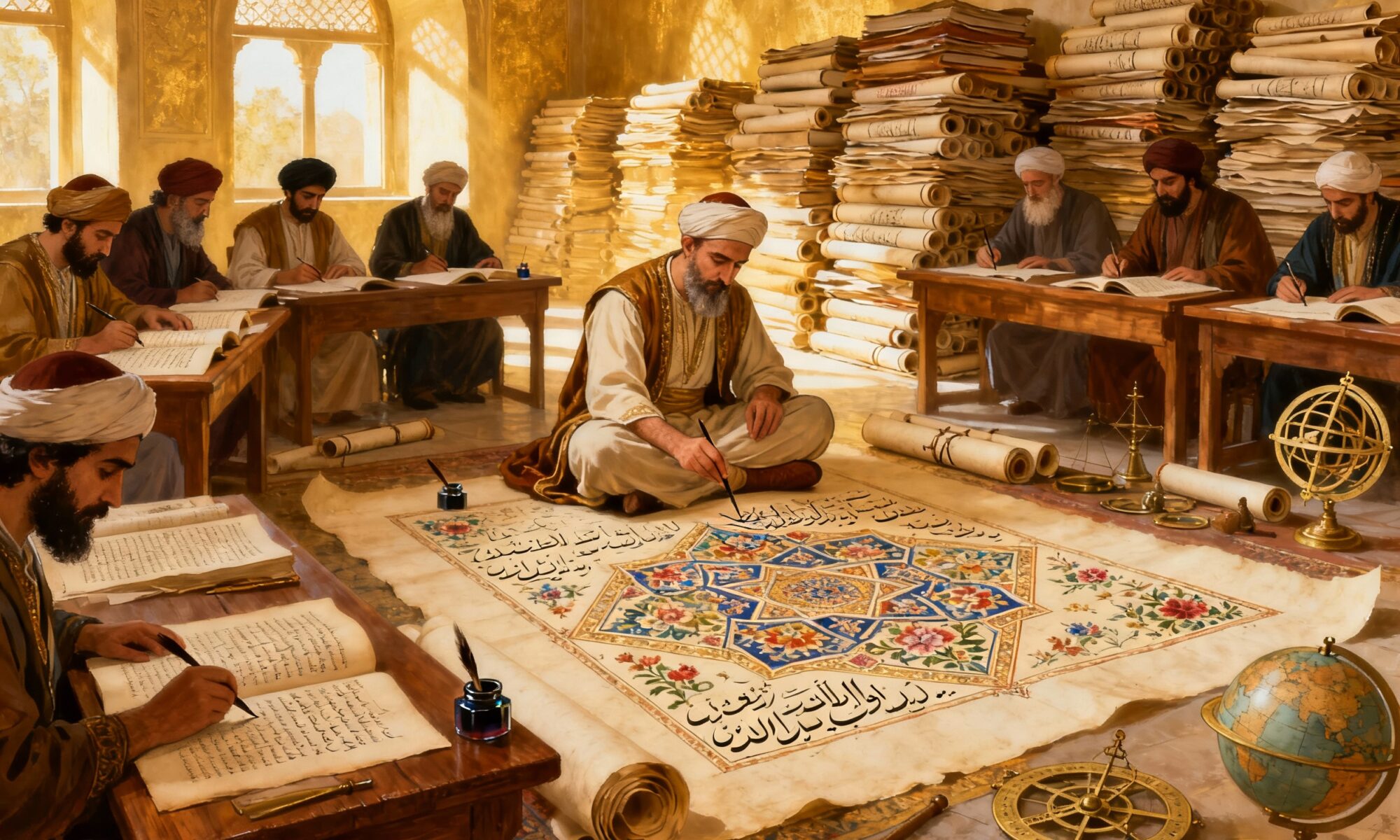

This wasn’t a passive accumulation of old books; it was an active, ambitious project to seek out, translate, and synthesize the scientific and philosophical wisdom of the known world. It was an era when scholars were celebrated like rock stars, and libraries were the epicenters of power and prestige.

A City Built for Knowledge

The story begins in 762 CE when the second Abbasid Caliph, al-Mansur, founded Baghdad as his new capital. Deliberately designed as a perfectly round city—the “Madinat al-Salam” or City of Peace—it was positioned at the crossroads of ancient trade routes, connecting Asia, Africa, and Europe. This strategic location made it a melting pot of cultures, ethnicities, and religions. Arabs, Persians, Christians, Jews, and people from as far as India lived and worked side-by-side.

From its inception, Baghdad was envisioned as a center of governance and commerce, but it rapidly evolved into a capital of learning. The Abbasid caliphs, particularly al-Mansur, Harun al-Rashid, and his son al-Ma’mun, understood that knowledge was power. To run a vast, complex empire, they needed practical knowledge of engineering, medicine, and mathematics. To bolster their cultural prestige, they sought the philosophical and literary treasures of older civilizations.

The House of Wisdom: An Intellectual Powerhouse

At the core of this intellectual explosion was the legendary Bayt al-Hikma, or “House of Wisdom.” What began as a private library for Caliph Harun al-Rashid was transformed by his son, Caliph al-Ma’mun (reigned 813-833 CE), into a public academy and translation institute unrivaled in the world.

The House of Wisdom was more than just a library. It was a bustling complex comprising:

- A massive library of manuscripts from across the world.

- A translation bureau staffed by the era’s best scholars.

- An astronomical observatory for charting the stars.

- A space for scholars to gather, debate, and conduct their own research.

Al-Ma’mun was personally invested in this project. A famous story tells of him having a dream in which the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle appeared to him, assuring him there was no conflict between reason and religion. Inspired, al-Ma’mun spared no expense in acquiring texts. He sent emissaries to the Byzantine Empire and other lands to buy or copy any manuscript they could find, reportedly paying for translations with their weight in gold.

From Athens, Persia, and India to Baghdad

The translation effort was astonishingly comprehensive, drawing from three major ancient traditions:

1. Greek: This was the cornerstone of the movement. Scholars painstakingly translated the foundational works of Western thought into Arabic. This included:

- Philosophy from Plato and Aristotle.

- Medicine from Galen and Hippocrates.

- Astronomy from Ptolemy.

- Mathematics and geometry from Euclid and Archimedes.

2. Persian: As the heirs to the Persian Sassanian Empire, the Abbasids absorbed centuries of their administrative, literary, and scientific knowledge. They translated royal histories, political treatises, and literary works like the animal fables of Kalila wa-Dimna, which had their own origins in India.

3. Indian: From the Indian subcontinent came crucial advancements, particularly in mathematics and astronomy. It was through translations of Indian scholars like Brahmagupta that the “Arabic numerals” we use today (including the revolutionary concept of zero) were introduced and popularized. Indian medical texts and astronomical tables were also eagerly studied and translated.

The Translators: A Bridge Between Worlds

The heroes of this story were the translators themselves, a remarkably diverse group of scholars. Many of the most important translators were not Arabs or Muslims. Nestorian Christians, who were often fluent in Greek, Syriac, and Arabic, were indispensable intermediaries. Often, a text would first be translated from Greek into Syriac (a language used in the Christian communities of the Middle East) and only then into Arabic.

The most celebrated of these figures was Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809-873 CE), a Nestorian Christian physician and scholar. He was the chief translator at the House of Wisdom and a towering intellectual figure. Hunayn’s method became the gold standard. He would collect several Greek manuscripts of a single work, carefully compare them to create the most accurate source text, and then render it into clear, elegant Arabic. He personally translated over 100 works by Galen alone, establishing the very vocabulary of Arabic medicine.

Beyond Preservation: A Legacy of Innovation

The Abbasid Translation Movement was not simply about preserving ancient knowledge like artifacts in a museum. It was a dynamic process of absorption, critique, and innovation. Arabic-speaking scholars didn’t just copy the ancients; they engaged with them, corrected their errors, and built upon their work to push the boundaries of knowledge.

This creative synthesis sparked a golden age of Islamic science and philosophy:

- In mathematics, Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi used Indian numerals and Greek geometric principles to create a new discipline he called al-jabr—the origin of our “algebra.” His work also introduced algorithms to the West.

- In medicine, Ibn Sina (Avicenna) wrote The Canon of Medicine, a monumental encyclopedia that combined Greek and Indian medical knowledge with his own clinical observations. It became the standard medical textbook in Europe for over 600 years.

- In optics, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) fundamentally challenged the Greek theory of vision, correctly arguing that light travels from an object to the eye. His insistence on proof through experimentation makes him a key founder of the modern scientific method.

Ultimately, this vast body of knowledge made its way back to Europe. Through cultural centers in Islamic Spain (Al-Andalus) and Sicily, these Arabic texts—containing the rescued wisdom of the Greeks alongside new Islamic discoveries—were translated into Latin. This re-introduction of classical philosophy and science was a crucial catalyst for the European Renaissance.

The Translation Movement was a testament to the power of intellectual curiosity and cross-cultural collaboration. It stands as a brilliant reminder that knowledge is a shared human heritage, and that the light of learning, once lit, can be passed across empires, languages, and centuries, illuminating the path for all who follow.