We live in the Information Age, a world built on data, algorithms, and digital records. We talk about “data being the new oil” and celebrate the tech gurus who manage and interpret it. But what if I told you that the role of the information technologist is not a modern invention? Eons before the first line of code was written, a powerful class of professionals wielded immense influence by mastering the most advanced technology of their day: writing.

Meet the scribes of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. They were far more than mere copyists. They were the accountants, lawyers, administrators, librarians, and civil engineers of their time. As the exclusive gatekeepers of all recorded knowledge, they were the indispensable cogs in the machinery of empire, the original information technologists who shaped the world’s first great civilizations.

The Dawn of Data: Cuneiform and Hieroglyphs

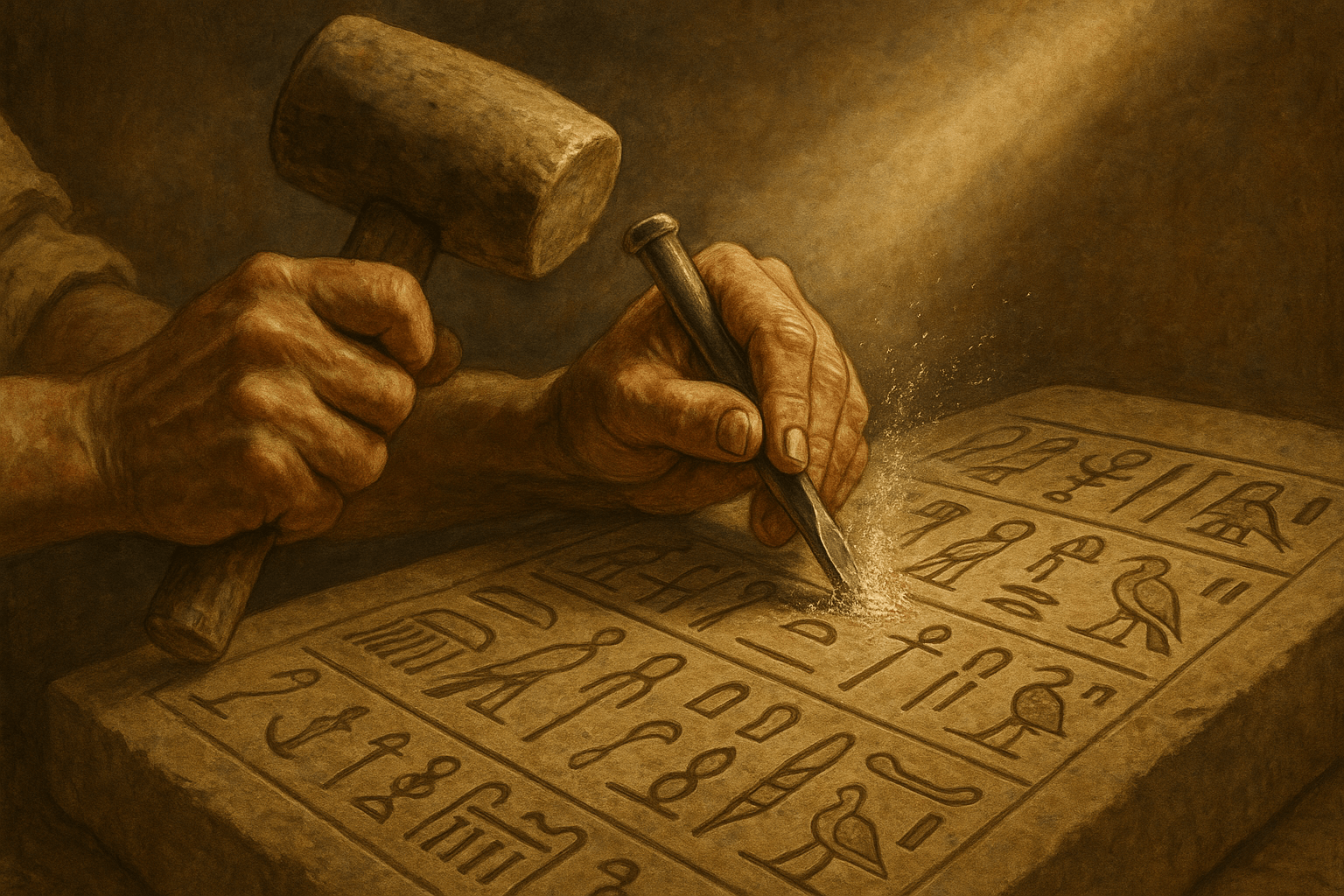

To understand the scribe’s power, one must first appreciate the complexity of ancient writing systems. Around 3200 BCE, the Sumerians in Mesopotamia developed cuneiform, a sophisticated system of wedge-shaped marks pressed into wet clay tablets. Almost simultaneously, the Egyptians created hieroglyphs, the beautiful “sacred carvings” that adorned tomb and temple walls.

These were not simple alphabets. Cuneiform and hieroglyphs each contained hundreds of signs representing syllables, whole words (logograms), and determinatives (signs that clarified the meaning of a word). To master them required years of dedicated study. For daily administrative and commercial use, Egyptian scribes also used faster, cursive scripts called Hieratic and later, Demotic. This multi-layered system ensured that literacy remained a highly specialized and protected skill.

Every sack of grain counted, every royal decree issued, every law codified, and every epic poem preserved had to pass through the hands of a scribe. Their tools—the reed stylus and clay tablet in Mesopotamia, the papyrus scroll and ink-filled palette in Egypt—were the hardware that ran the software of civilization.

Forging a Scribe: The Grueling Path to Literacy

Becoming a scribe was a ticket to the upper echelons of society, but the journey was arduous. Training began at a young age, typically for boys from affluent or established scribal families.

In Mesopotamia, a boy attended the Edubba, or “tablet house.” The curriculum was punishing, and discipline was notoriously harsh. Surviving texts from Sumerian schoolboys complain about long days and frequent beatings. One proverb states, “He who would excel in the school of the scribes must rise with the dawn.” Students spent years copying lists of signs, vocabulary, proverbs, and eventually, classic literary texts. But their education went far beyond writing. They studied:

- Mathematics: Essential for accounting, surveying land, and calculating the resources needed for massive construction projects.

- Law: Drafting contracts for everything from marriage to land sales and recording judicial decisions.

- Administration: Learning the complex workings of the temple or palace bureaucracy.

Similarly, in Egypt, aspiring scribes entered institutions like the Per Ankh, or “House of Life”, which was often attached to a temple. Here, they meticulously practiced their craft, memorizing texts and mastering the calculations needed to manage the vast agricultural wealth of the Nile valley. The famous Egyptian sculpture, “The Seated Scribe”, now in the Louvre, captures the ideal: alert, poised, and ready, a testament to the importance and dignity of his profession.

More Than Just Writers: The Many Hats of a Scribe

A fully trained scribe was a versatile and indispensable expert. Their ability to read, write, and calculate gave them access and authority in every sector of society. They weren’t just recording events; they were actively managing them.

An Egyptian scribe might spend his morning calculating the tax assessment for a farmer’s field, his afternoon overseeing the distribution of rations to pyramid builders, and his evening drafting a magical spell for a noble’s journey into the afterlife. They were the project managers of the pharaohs. The vizier Imhotep, architect of the first step pyramid, began his illustrious career as a high priest and scribe.

In Mesopotamia, a scribe could be found in the bustling marketplace finalizing a trade agreement, in the temple archives cataloging astronomical observations, or on a military campaign tracking supplies and casualties. They were the memory and the operating system of the state. The famous Library of Ashurbanipal, which held tens of thousands of clay tablets including the Epic of Gilgamesh, was a monumental achievement of scribal organization and preservation.

The Scribe’s Reward: Status, Power, and Immortality

The arduous training paid off handsomely. Scribes occupied a privileged position in the social hierarchy. They were exempt from the backbreaking manual labor that was the lot of most people, as well as from military conscription.

An Egyptian text known as The Satire of the Trades vividly illustrates this prestige. A father advises his son to become a scribe, mocking all other professions:

“I have seen the metalworker at his task at the mouth of his furnace, with fingers like the claws of the crocodile, and he stinks more than fish-roe… The potter is smeared with soil… I shall also describe to you the bricklayer… his arms are destroyed by his work… Be a scribe. It saves you from toil and protects you from all manner of work.”

This social mobility was unique. While most people were born into their station, a clever boy with the right training could rise to a position of great influence. Their power was subtle but absolute. A king could have a vision, but it was the scribe who gave it form, communicated it, and managed its execution. They controlled the flow of information, and in doing so, they controlled the levers of power.

Ultimately, the scribes achieved a form of immortality. While the names of most kings and warriors are lost to time, the work of the scribes endures. Every historical record we study, every piece of ancient literature we read, and every economic transaction we analyze exists only because a scribe once painstakingly recorded it. They not only managed their world but preserved it for ours.

So the next time you tap out an email or update a spreadsheet, take a moment to remember your professional ancestors. The scribes of Egypt and Mesopotamia were the original masters of information, proving that for millennia, the power of civilization has rested in the hands of those who can read, write, and, most importantly, control the record.