Imagine you are a king in Bronze Age China, more than 3,000 years ago. A drought is searing your fields, whispers of rebellion are stirring in a vassal state, and your favorite consort has fallen gravely ill. How do you decide your next move? For the rulers of the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), the answer wasn’t found in a council of advisors alone, but in a direct line to the divine: the sizzling, cracking oracle bones.

This practice, known as scapulimancy, was the bedrock of Shang political and religious life. It was a sophisticated ritual for consulting ancestors and deities about the future, and in the process, it gave birth to the earliest known form of Chinese writing. These inscribed bones provide an unparalleled window into the minds of ancient kings, revealing their deepest anxieties and daily concerns.

The Sacred Ritual: How to Speak with a Bone

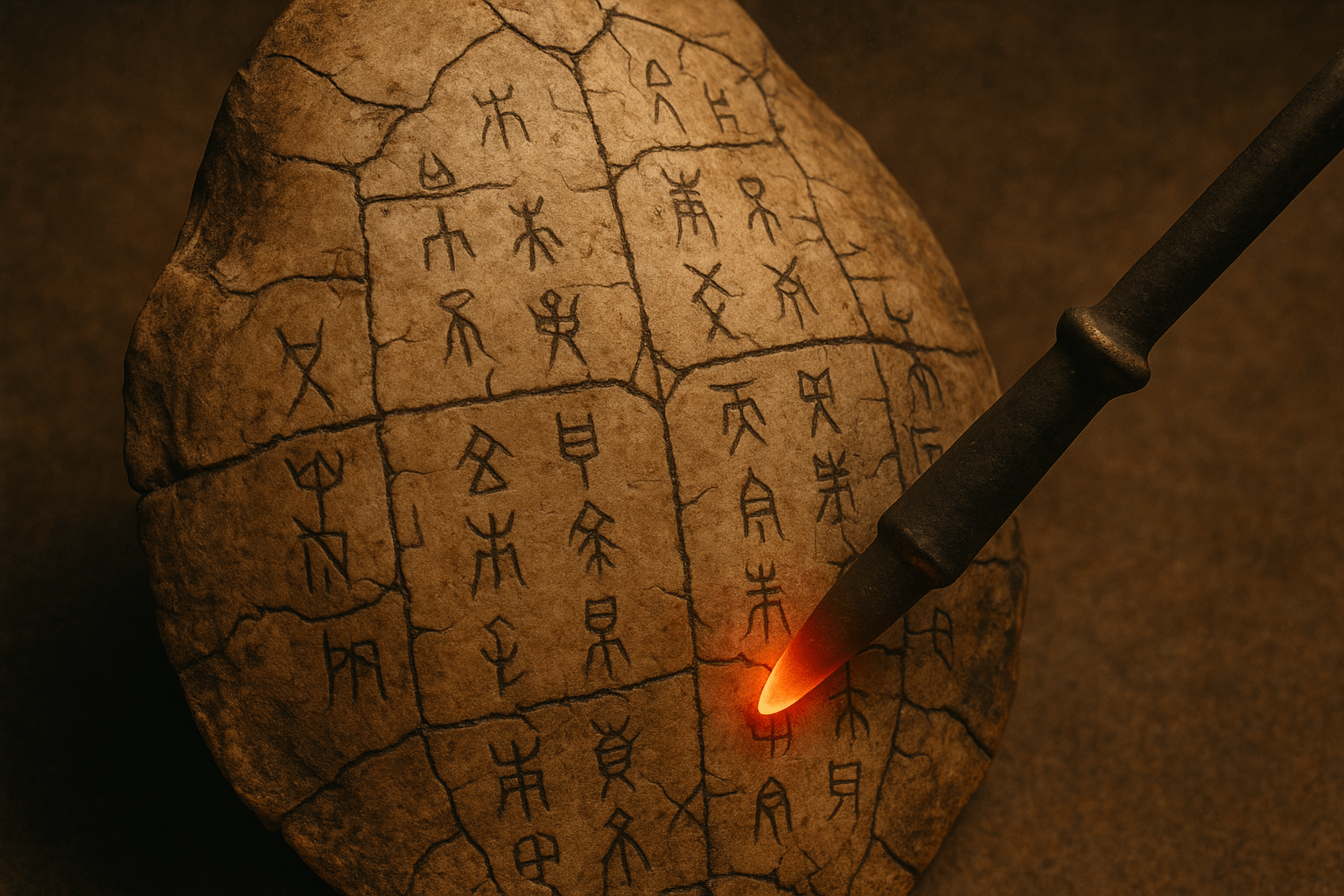

The term “scapulimancy” comes from the Latin scapula (shoulder blade) and the Greek manteia (divination). While the shoulder blades of oxen were commonly used, the Shang also practiced “plastromancy”, using the plastron (the flat underside) of turtle shells. These materials were not chosen at random; turtles held a cosmic significance, with their domed top shell representing the heavens and the flat plastron representing the earth.

The divination process was a meticulous and solemn affair, performed by professional diviners or even the king himself. It followed a clear sequence of events:

- Preparation: The bones or shells were carefully sourced, cleaned, scraped, and polished to create a smooth surface. This was a skilled task, as the thickness and quality of the bone were crucial.

- Hollowing: On the back of the bone, a series of oval-shaped hollows or pits were chiseled or drilled in neat rows. This step was key; the thinned-out bone would crack in a more controlled manner when heat was applied.

- The Charge: The diviner would present a topic for divination, known as a “charge.” This was a declarative statement, often posed in both positive and negative forms to get a clear answer. For example: “The ancestors approve of the king’s military campaign”, followed by, “The ancestors do not approve of the king’s military campaign.”

- Applying Heat: A glowing-hot bronze rod or a piece of burning wood was plunged into the hollows. The intense, localized heat caused the bone to expand and crack on the front surface, often with an audible puk (卜) sound—a character that, fittingly, now means “to divine.”

- Interpretation: The king or head diviner would then interpret the pattern of the resulting cracks (卜兆, bǔzhào). The shape, angle, and direction of the fissures determined the answer from the spiritual realm. A favorable crack might be interpreted as “auspicious”, while an unfavorable one was deemed “inauspicious.”

The Questions of a King

The oracle bones were not used for trivial fortune-telling. They were a tool of statecraft, a way for the Shang ruler to seek legitimacy and guidance from the spirit world for nearly every decision. The thousands of recovered oracle bones are a catalogue of royal concerns, which can be grouped into several key areas:

- State & Military: “Will we be victorious in the campaign against the Fang state?” “Should we forge an alliance with the neighboring Qiang?” “Is it an auspicious time to found a new settlement?”

- Harvest & Weather: “Will it rain in the next five days?” “Will the millet harvest be abundant?” “Is the Spirit of the Yellow River angry?”

- Royal Life: “Will the queen’s childbirth be fortunate?” (Often followed by, “Will it be a son?”) “Is the king’s toothache caused by an ancestral curse?” “Will the upcoming hunt be successful?”

- Ritual & Sacrifice: “Should we sacrifice ten oxen to Ancestor Di Yi?” “Is the offering sufficient?”

These questions reveal a worldview where the physical and spiritual realms were deeply intertwined. The health of the king, the success of the harvest, and the outcome of a battle were all subject to the will of powerful nature deities and, most importantly, the spirits of the royal ancestors.

From Divine Cracks to Chinese Characters

Perhaps the most profound legacy of scapulimancy is its connection to the birth of writing. After a divination was performed and interpreted, scribes would often carve a record of the entire event directly onto the bone or shell. This is what makes oracle bones a true historical treasure.

A complete inscription typically included four parts:

- Preface (叙辞): The date of the divination (using the traditional 60-day cycle) and the name of the diviner.

- Charge (命辞): The question or topic being posed to the spirits.

- Prognostication (占辞): The king’s interpretation of the cracks and his prediction of the outcome.

- Verification (验辞): A note, sometimes added weeks or months later, recording what actually happened. For example, “On day X, it did indeed rain.”

The script used for these inscriptions, known as Oracle Bone Script (甲骨文, jiǎgǔwén), is the oldest confirmed corpus of Chinese writing and the direct ancestor of the characters used today. While many characters were pictographic—a recognizable drawing of a horse (馬), a fish (魚), or a person (人)—the system was already highly sophisticated, including abstract concepts and phonetic loan characters. Studying these ancient inscriptions allows us to trace the fascinating evolution of one of the world’s oldest continuous writing systems.

“Dragon Bones” and the Rediscovery of a Dynasty

For centuries, the story of the Shang Dynasty was just that—a story, recorded in later texts but lacking hard proof. The discovery that would change everything came about by accident. In the late 19th century, farmers in the village of Xiaotun, near Anyang in Henan province, were unearthing caches of old bones. Believing them to be “dragon bones” (龍骨, lóng gǔ) with healing properties, they sold them to apothecaries, who ground them into powder for traditional medicine.

The story goes that in 1899, the scholar and chancellor of the Imperial Academy, Wang Yirong, was prescribed this very medicine. Before the bones were pulverized, he noticed the strange, ancient script carved into their surfaces. Recognizing their immense historical value, he and other scholars began collecting them. Their efforts led archaeologists to Xiaotun, which was soon identified as Yinxu (the “Ruins of Yin”), the last great capital of the Shang Dynasty. The “dragon bones” were, in fact, the royal archives.

The excavations at Yinxu have since yielded over 150,000 oracle bone fragments, providing concrete, irrefutable evidence of the Shang Dynasty’s existence. They confirmed its king lists, its social structure, and its religious beliefs, transforming it from a semi-mythical period into a tangible, well-documented chapter of world history.

The oracle bones are more than just ancient artifacts. They are a direct conversation with the past. In their cracks and carvings, we see the foundation of a civilization: a system of belief that ordered the universe, a method of governance that sought divine sanction, and the birth of a writing system that would shape East Asian culture for millennia.