Archaeology is increasingly pointing to a powerful candidate: the Sarmatians. These nomadic people, who dominated the Pontic-Caspian Steppe (modern-day Ukraine and southern Russia) from roughly the 5th century BCE to the 4th century CE, are rewriting our understanding of ancient gender roles and providing a solid, historical basis for the Amazon myth.

The Greek Legend of the Amazons

Before we dig into the archaeological evidence, it’s important to understand the Greek perspective. To the Greeks, the Amazons were the ultimate “other.” They represented an inversion of the established order. In Greek city-states, women’s lives were largely confined to the home. They were excluded from politics, warfare, and public life. The Amazons, therefore, were a fantastical and terrifying concept.

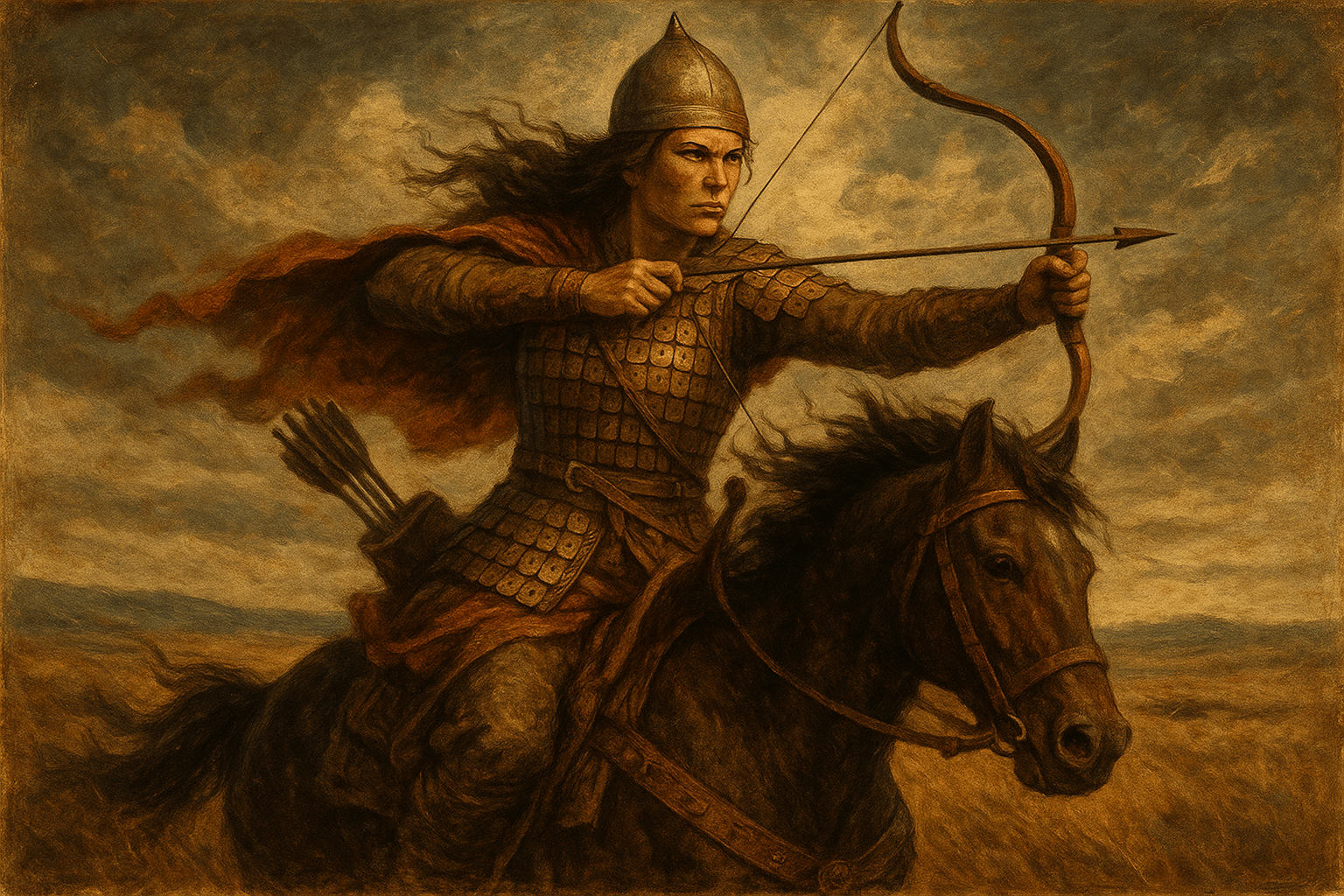

According to myths, they lived on the fringes of the known world, often located around the Black Sea—a region the Greeks called Scythia. They were master horsewomen and archers, fighting with a ferocity that matched any man. Tales of them cauterizing one breast to better draw a bow (a myth for which there is no evidence, and the term amazon likely has a different origin) only added to their fearsome reputation. They were a convenient foil for Greek heroes, a chaotic force of nature for the civilized Greek male to conquer and tame.

Unearthing the Truth: Enter the Sarmatians

For centuries, the Amazons were dismissed as pure fantasy. But in the 20th and 21st centuries, excavations across the Eurasian steppe began to uncover something extraordinary. Archaeologists studying burial mounds, known as kurgans, found that a surprising number of graves containing weapons and armor belonged not to men, but to women.

These weren’t isolated cases. In some Sarmatian cemeteries, and those of the related Scythians before them, as many as 25-30% of the warrior graves belong to females. These women were not just buried with a symbolic dagger; they were interred with the full toolkit of a steppe warrior:

- Arrowheads: Dozens of bronze or iron arrowheads, often found in quivers placed by their side.

- Swords and Daggers: Long iron swords and short daggers (akinakes) were common, indicating close-quarters combat.

- Spears: The primary weapon for a mounted warrior.

- Armor: Evidence of scale armor has also been found in some female graves.

These discoveries forced a radical reassessment. The evidence was clear: a significant portion of the fighting force among these steppe peoples was female.

More Than Just Burials: Skeletons That Tell a Story

The evidence goes far beyond grave goods. Analysis of the skeletal remains themselves paints a vivid picture of a hard-lived, martial life. Many of the female skeletons show tell-tale signs of being warriors:

Battle Wounds: Archaeologists have found female skeletons with injuries consistent with combat. Healed (and unhealed) sword cuts on skulls, broken arms from parrying blows, and even arrowheads still embedded in bone provide direct, undeniable proof that these women fought and sometimes died in battle.

A Life on Horseback: Constant horse riding from a young age physically changes the body. Many of these female skeletons exhibit bowed leg bones and developed muscle attachments characteristic of a life spent in the saddle. They weren’t just warriors; they were expert cavalry.

This physical evidence is crucial. It confirms that the weapons in their graves were not just ceremonial. These were not simply “honorary” warriors; they were active participants in the violent, demanding world of steppe nomadism.

Herodotus: The Bridge Between Myth and History

One of the most fascinating links between the Greek myth and the Sarmatian reality comes from the “Father of History” himself, Herodotus. Writing in the 5th century BCE, Herodotus recorded a story about the origins of the Sauromatians (a people closely related to or synonymous with the early Sarmatians).

He claimed they were descended from a union between a group of Scythian men and a band of Amazons. According to his account, the Amazon women refused to give up their old ways. He wrote that Sarmatian women “ride on horseback, hunt with their men and in war, and wear the same dress as the men.” He even noted a marriage custom where a young woman was not permitted to marry until she had killed an enemy in battle.

For a long time, Herodotus’s account was considered another fantastical tale. But with the advent of modern archaeology, his words now seem less like myth and more like a remarkably accurate ethnographic observation, albeit one embellished for his Greek audience. He was describing a real cultural practice that he or his sources had encountered on the shores of the Black Sea.

So, Were They the Real Amazons?

The answer is a nuanced yes. The Sarmatian warrior women were not the man-hating, baby-abandoning, single-breasted caricatures of Greek legend. Those elements were likely added by the Greeks to make the stories more sensational and to emphasize their “unnatural” inversion of Greek societal norms.

However, the core of the Amazon myth is undeniably present in the Sarmatian historical record:

- They were women who were skilled riders and archers.

- They fought in battle alongside men.

- They held positions of power and respect, as evidenced by the rich grave goods in some female burials, suggesting they could be chieftains or leaders.

- They lived in the exact geographical region where the Greeks placed the Amazons.

The most likely scenario is that Greek traders, colonists, and soldiers who traveled to the Black Sea encountered these formidable Sarmatian women. The tales of these horse-riding, bow-wielding barbarian women traveled back to Greece, where they were filtered through a lens of myth, exaggeration, and cultural bias. Over time, these real-world encounters were transformed into the legend of the Amazons we know today.

The reality, in many ways, is more compelling than the myth. The Sarmatian warrior women were not a mythical race. They were real people—daughters, and perhaps mothers and sisters—who played a vital and active role in the defense and survival of their tribe. The sun-scorched steppes of Eurasia, once thought to be home to legends, were in fact the domain of true warrior women whose stories are only now being fully told.