An Insatiable Appetite for Timber

To understand the scale of Roman deforestation, we must first grasp their near-total dependence on wood. It was the indispensable raw material of the ancient world, the oil and plastic of its day, crucial to every facet of life, industry, and war.

The Roman demand for wood was staggering, driven by several key areas:

- Construction and Engineering: While we marvel at their stone structures, we forget the immense wooden scaffolding required to build them. Aqueducts, bridges, and amphitheaters all required vast timber frameworks. On the frontiers, entire forts, watchtowers, and palisades were built from wood. Hadrian’s Wall in Britain, for example, was initially planned with a turf and timber wall, and its associated forts and milecastles consumed an estimated one million cubic feet of oak.

- Fuel for the Masses: Wood and its derivative, charcoal, were the primary sources of energy. They heated the homes of millions, from humble apartments in Rome to sprawling villas in Gaul. Most famously, they fueled the massive public baths, or thermae. Keeping the colossal Baths of Caracalla in Rome heated around the clock is estimated to have required tons of wood every single day.

- The Engine of Industry: Roman industry ran on fire. The smelting of metals—iron for weapons, lead for pipes, silver and gold for currency—demanded colossal amounts of charcoal to achieve the necessary high temperatures. The silver mines at Rio Tinto in Spain, for example, were so productive that pollution from their smelting operations is still detectable in Greenland’s ice cores. This industrial output was only possible through the systematic clearing of entire landscapes for fuel. Glassmaking, pottery kilns, and brickworks added to the constant demand.

- Naval Dominance: Rome’s control of the Mediterranean—their Mare Nostrum (“Our Sea”)—was predicated on a massive navy. A single Roman warship, a quinquereme, could require up to 400 mature trees, primarily oak and pine. During the First Punic War against Carthage, Rome reportedly built a fleet of over 200 ships in a matter of months, a feat of logistics that would have denuded entire forests along the Italian coast.

- Agricultural Expansion: To feed the ever-growing population of the city of Rome and its legions, vast tracts of land were needed for agriculture. This often meant clear-cutting forests to make way for grain fields, olive groves, and vineyards. This was a double blow: not only were the trees removed, but the land’s use was permanently changed, preventing any chance of reforestation.

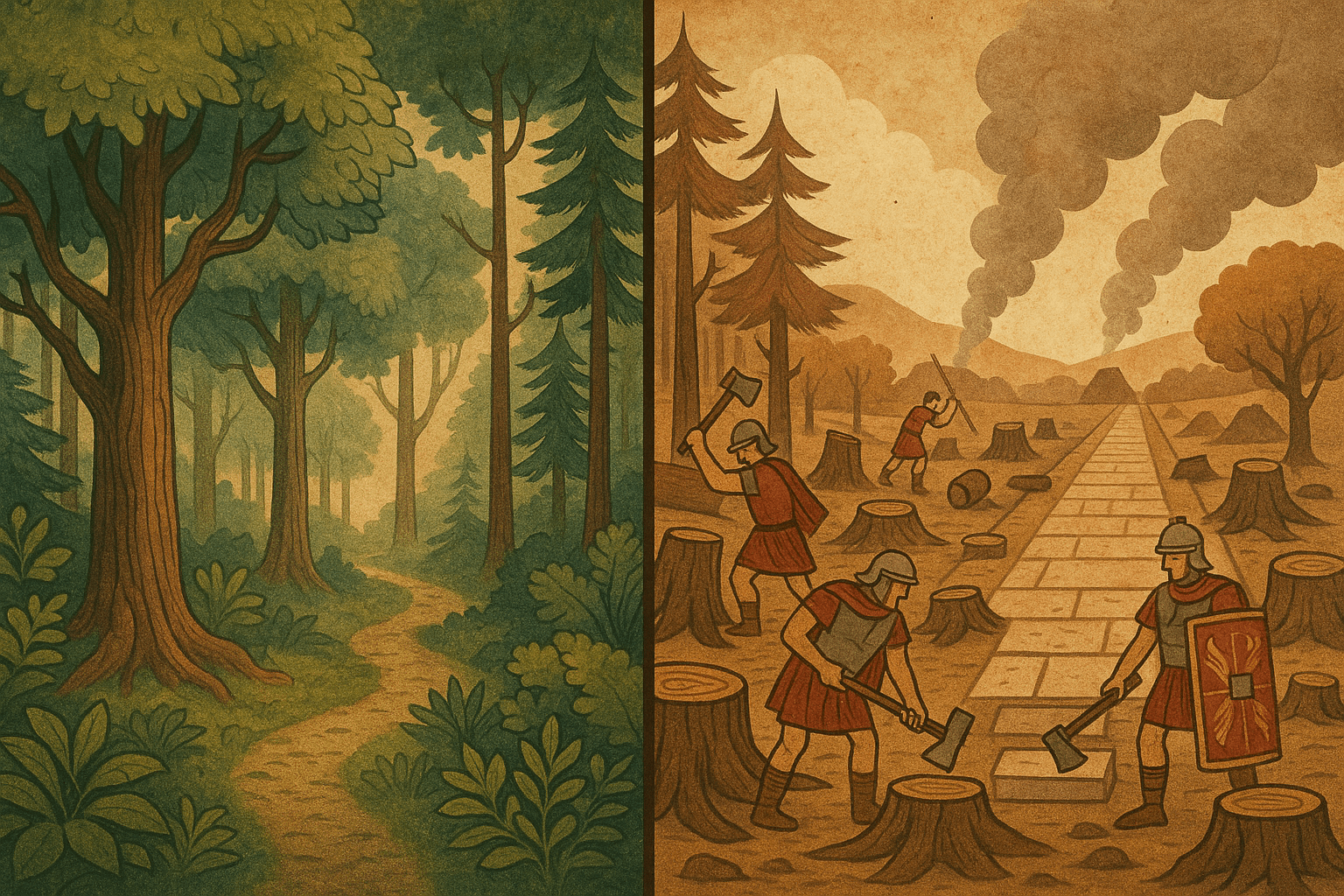

The Axe Falls Across an Empire

The environmental impact of this demand was written across the map of the Roman world. The deforestation began in Italy itself. The once heavily forested Apennine Mountains were stripped of their accessible timber early in the Republic’s history. By the late Republic, authors like the geographer Strabo noted that the mountains near Rome, once rich with timber for shipbuilding, were now exhausted, forcing the Romans to source wood from the far north.

As the empire expanded, so did the “timber frontier.” In Spain and Gaul, mining operations created “industrial deserts” around them. The forests of the Iberian Peninsula were consumed to fuel the smelters for its legendary silver and lead mines. In North Africa, a region we now associate with arid landscapes, the story is even more dramatic. The coastal plains of modern-day Tunisia and Algeria were the breadbasket of Rome, producing enormous quantities of grain. This region was once far more wooded, home to the now-extinct North African elephant. Roman clearing for agriculture, coupled with the demand for timber, fundamentally altered the ecosystem, contributing to soil erosion and long-term desertification from which the area never fully recovered.

Even on the misty frontiers of Britain and Germany, the Roman military machine was a powerful agent of deforestation. Clearing forests was a tactical move, designed to deny cover to hostile tribes and create clear lines of sight between forts. The construction of the vast network of forts and roads along the German Limes frontier required a constant supply of local timber for construction and fuel.

Ancient Awareness and Unintended Consequences

Were the Romans oblivious to the impact they were having? Not entirely. They possessed a sophisticated understanding of agriculture and forestry, including practices like coppicing (a method of harvesting wood that allows trees to regrow). Writers like Pliny the Elder lamented the loss of certain forests and noted how the demand for luxury items was stripping hillsides bare. The philosopher Seneca even complained about the air pollution in Rome, thick with “the heavy air of the smoky kitchens.”

However, this awareness did not translate into conservation policy. The needs of the state, the military, and the economy always took precedence. The consequences were felt in their own time. As local timber became scarce, the Romans had to establish complex, long-distance supply chains, shipping wood from the Black Sea, the Alps, and the Atlas Mountains in Africa. This increased costs and created logistical vulnerabilities.

One of the most powerful examples of an unintended consequence was the silting of harbors. Widespread deforestation in the hills surrounding rivers led to massive soil erosion. This sediment was carried downstream and deposited at river mouths, choking ports. Ostia, the vital port of Rome itself, suffered from this process, forcing the construction of a new, larger harbor complex, Portus, under emperors Claudius and Trajan—a monumental engineering project made necessary in part by an environmental problem of their own making.

A Cautionary Tale from the Ancient World

The Roman Empire’s rise and success were inextricably linked to its ability to exploit natural resources on an unprecedented scale. Their mastery of engineering and organization allowed them to harvest the forests of their world to build cities, fund armies, and feed their people. But this success came at a steep environmental price, leaving a legacy of altered landscapes, eroded soil, and shifted ecosystems that we can still see today.

The story of Rome’s war on forests is not just an obscure historical footnote. It is a profound, large-scale case study on the complex relationship between civilization, technology, resource consumption, and the environment. It serves as a powerful reminder that even the mightiest empires are ultimately dependent on the health of the natural world, and that the consequences of its exploitation can echo for millennia.