Imagine the scene: thousands of years before the advent of modern medicine, a person lies with their head held steady. Another individual, perhaps a shaman, healer, or early surgeon, leans over them, armed not with a sterile steel drill, but with a sharpened piece of flint or obsidian. Carefully, methodically, they begin to scrape, cut, or drill a hole into the patient’s skull. This intense and startling procedure is trepanation (or trephination), and it stands as one of the oldest surgical practices known to humanity.

Far from being a rare and bizarre ritual, trepanation was a surprisingly common and widespread phenomenon. Archaeologists have unearthed trepanned skulls on every inhabited continent, providing a silent yet powerful testament to our ancestors’ daring attempts to interact directly with the brain and head.

What is Trepanation?

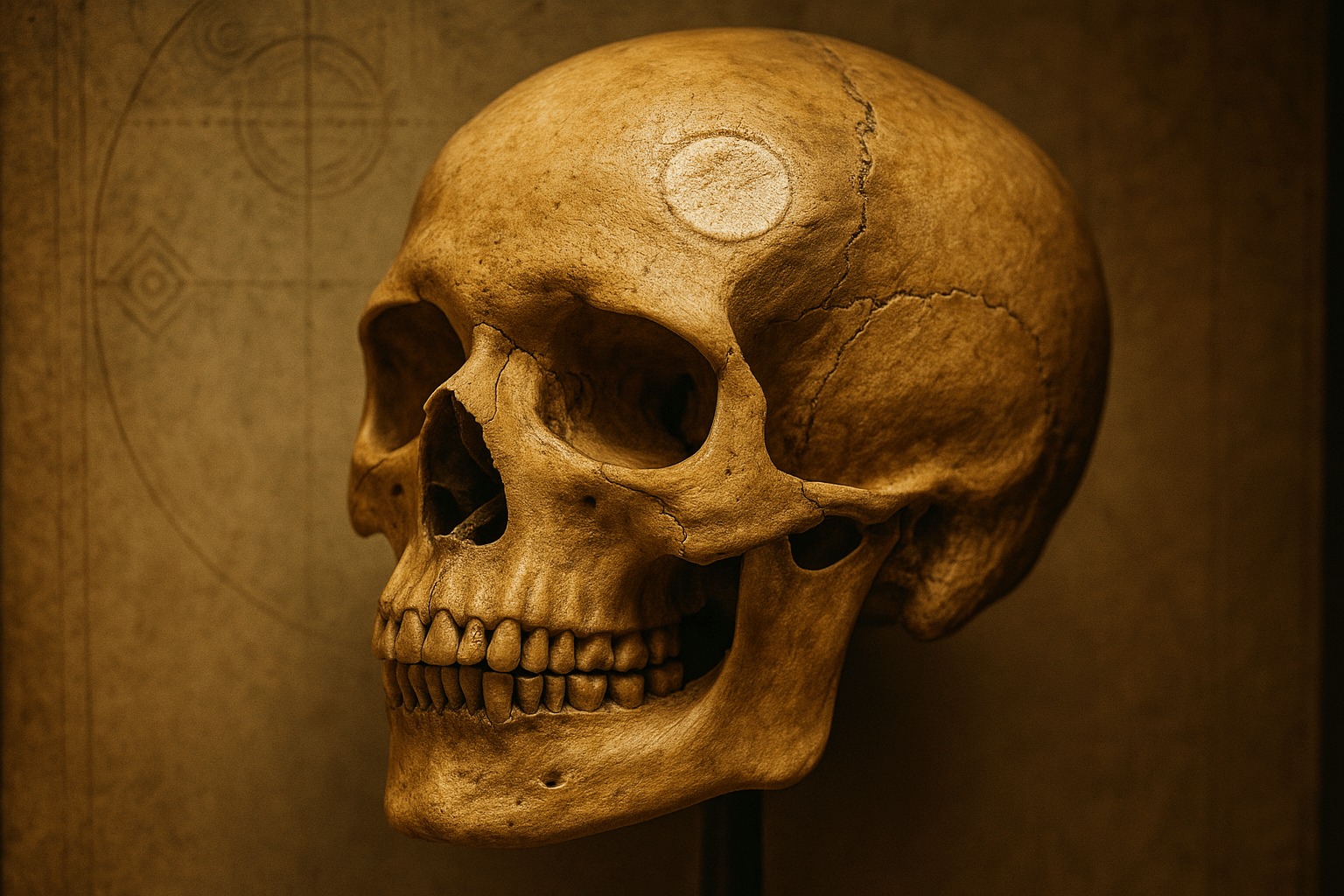

In simple terms, trepanation is the intentional act of creating an opening in the cranium of a living person without damaging the underlying brain tissue. The resulting hole, or trepanation, could be circular, square, or irregular, and the piece of bone removed—known as a rondelle—was sometimes kept as a talisman or amulet.

While it may sound crude, the evidence suggests it was often performed with great care and skill. Many skulls show clear signs of healing and bone regrowth around the edges of the hole, indicating that patients frequently survived the procedure and lived for months, years, or even decades afterward.

A Global Prehistoric Phenomenon

The practice of trepanation dates back to at least the Neolithic period. One of the oldest known examples comes from Ensisheim, France, dating to around 5000 BCE. The skull of an adult male shows two trepanation holes, one of which displays significant healing, demonstrating a successful operation.

But this was no isolated incident. Trepanned skulls from the Stone Age have been found across Europe, from Spain and Portugal to Poland and Russia. The practice, however, wasn’t confined to one continent or time period.

Perhaps the most prolific and skilled practitioners were the ancient cultures of Peru, particularly the Incas, around 1400 CE. Thousands of trepanned skulls have been discovered there, making up a significant portion of all known examples worldwide. The Incas experimented with various techniques and achieved astonishingly high success rates. Some studies of late-Inca period skulls show survival rates as high as 80-90%, a figure that would put to shame many European operating theaters of the 19th century.

Unraveling the ‘Why’: Medicine, Magic, or Both?

The most compelling question surrounding trepanation is: why did they do it? Since these ancient peoples left no written surgical manuals, we must rely on archaeological evidence and anthropological inference. The motivations were likely a complex blend of the medical and the magical.

Medical Intervention

The most straightforward theory is that trepanation was a pragmatic medical treatment.

- Head Trauma: A violent blow to the head can cause the skull to fracture and lead to life-threatening intracranial bleeding (an epidural hematoma). Relieving the pressure by drilling a hole is a logical, and often life-saving, procedure still used today (in the form of a craniotomy). Many trepanned skulls show evidence of pre-existing fractures, supporting this theory.

- Chronic Ailments: Ancient peoples may have used trepanation to “cure” conditions they could not otherwise explain, such as severe, recurring headaches (migraines), seizures (epilepsy), or other neurological disorders. The belief might have been that the ailment was caused by pressure or a malevolent entity trapped inside the skull that needed an escape route.

Ritual and a Spiritual Gateway

It’s impossible to separate ancient medicine from magic and spirituality. In a world where illness was often attributed to supernatural forces, drilling a hole into the head took on profound ritualistic meaning.

- Releasing Evil Spirits: For conditions like epilepsy or mental illness, the hole was likely seen as a literal doorway to allow the evil spirit causing the affliction to escape. The procedure was as much an exorcism as it was a surgery.

- Rites of Passage: Some anthropologists speculate that trepanation may have been part of an initiation rite, a way to elevate a person’s status or grant them shamanic powers and a new level of consciousness.

- Post-Mortem Amulets: Not all trepanations were performed on the living. Some skulls show holes created after death. In these cases, the purpose was likely to retrieve the piece of a skull (the rondelle), which may have been worn as a protective amulet or believed to hold the spirit of the deceased.

The Ancient Surgical Toolkit

The skill of these prehistoric surgeons is all the more impressive given their tools. There were no electric drills or laser saws. Instead, they relied on what their environment provided. Tools were crafted from sharp-edged materials like flint and obsidian (volcanic glass).

Archaeologists have identified several distinct techniques:

- Scraping: The surgeon would use a sharp-edged tool to slowly and painstakingly scrape away the bone in a circular motion until a hole was formed. This was a slow but relatively safe method, as it minimized the risk of accidentally piercing the dura mater (the protective membrane around the brain).

- Grooving: This involved cutting a circular groove into the skull and then carefully prying out the isolated disc of bone.

- Boring and Cutting: The surgeon would drill a series of small, connected holes using a pointed borer and then cut the bone between them to remove the central piece.

How did they manage pain and infection? While we can’t be certain, it’s likely they used potent botanical substances. In Peru, for example, coca leaves (the source of cocaine) were a well-known anesthetic. Other plants with antiseptic or pain-relieving properties may have been used to clean wounds and help patients through the ordeal.

A Legacy in Bone

Trepanation is a stark and visceral reminder of our ancestors’ ingenuity and their enduring drive to heal. It represents a critical moment in human history: the first time we dared to intentionally operate on the very seat of consciousness. While we may view it through a modern lens of horror, for ancient peoples it was a fusion of cutting-edge medical technology and profound spiritual belief.

The skulls they left behind are not just archaeological curiosities; they are the medical charts of the ancient world, written in bone. They tell a story of pain, desperation, and an astonishing degree of surgical skill that, for thousands of years, offered a glimmer of hope against trauma and disease.