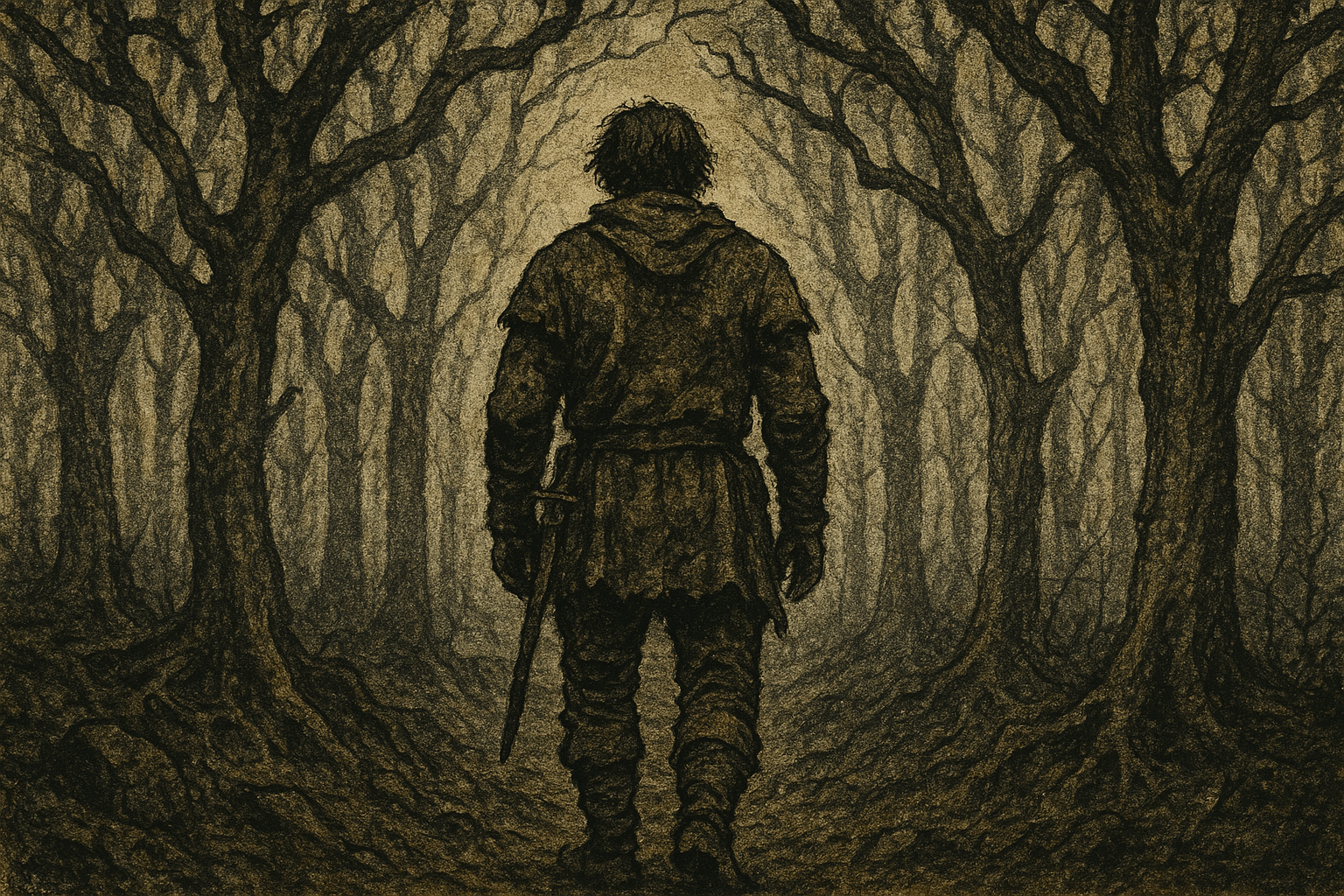

We often picture the medieval outlaw through a romantic lens: a charming rogue like Robin Hood, dwelling merrily in the greenwood, defying a corrupt sheriff, and championing the poor. But this beloved folklore masks a far grimmer and more terrifying legal reality. To be declared an “outlaw” in the Middle Ages was not to become a dashing fugitive; it was to be legally erased, to suffer a “civil death”, and to be designated a caput gerat lupinum—a “wolf’s head”, whom any man could hunt and kill without consequence.

What Did It Mean to Be an Outlaw?

In a world where law, status, and community were everything, outlawry was the ultimate sanction. It was a formal legal process, not simply a term for a criminal on the run. The most common path to outlawry was a failure to appear in court. When a person was accused of a serious crime (a felony), they would be summoned to face justice. If they failed to answer the summons multiple times, they were effectively showing contempt for the king’s law and the entire legal structure.

The court would then declare them an outlaw. This declaration had immediate and devastating consequences:

- Civil Death: The outlaw ceased to exist as a legal person. They could not sue in court, inherit property, make a valid will, or perform any legal act. They were, in the eyes of the law, already dead.

- Forfeiture of Property: All land and possessions owned by the outlaw were forfeited to their feudal lord or the Crown. Their family was often left destitute, punished for the actions of a relative they might not have seen in months.

- Severance from Community: They were cast out from the protection of not just the law, but of society itself. Harboring or helping an outlaw was a serious crime, meaning friends and even family had to turn them away on pain of prosecution.

The Terrifying Status of the “Wolf’s Head”

The most chilling aspect of outlawry was the concept of the “wolf’s head.” This ancient Germanic legal idea, formalized in English law around the 13th century by the legal writer Bracton, stipulated that the outlaw wore a wolf’s head. He was no longer a man, a member of the community, or a subject of the king; he was a predatory beast.

This was not just a metaphor. It meant that the outlaw was stripped of the most fundamental protection of all: the right to life. Any person who encountered an outlaw could kill them on sight, and not only would they not be charged with murder, they might even be entitled to a reward. To prove the deed, the slayer would often be required to bring the outlaw’s head to the authorities. The outlaw was a walking dead man, hunted like an animal, with a price on his head and no place to hide.

While this “kill on sight” rule was slowly softened in England by the later Middle Ages—requiring the outlaw to be resisting arrest to be lawfully killed—the principle remained. The outlaw existed in a state of constant, mortal peril, where every stranger was a potential executioner.

From English Forests to Icelandic Sagas

The practice of outlawry was not unique to England. It was a powerful tool of social control across medieval Europe, taking on unique regional characteristics.

In Viking Age Iceland, outlawry was a cornerstone of the legal system detailed in their epic sagas. Icelandic law distinguished between two forms. The lesser form, fjörbaugsgarðr, was a temporary three-year sentence of exile. The more severe form, skóggangr, meant the person was declared a “forest-man” and became a full outlaw for life. He could be killed without penalty, and anyone offering him aid for more than a few nights would also be outlawed. The famous Grettir’s Saga tells the story of Grettir the Strong, who survived as an outlaw in the harsh Icelandic wilderness for nearly 20 years—a feat so incredible it cemented his legendary status precisely because everyone knew such survival was nearly impossible.

In England, outlawry became deeply intertwined with the royal forests. These vast tracts of land, governed by their own harsh “Forest Law” designed to protect the king’s hunting, became the natural refuge for those cast out from society. It was here, in places like Sherwood or the Fens, that the reality of outlaw life and the legend of Robin Hood converged. Figures like Hereward the Wake, an 11th-century Anglo-Saxon noble who resisted the Norman Conquest, and Fulk FitzWarin, a 13th-century nobleman who fell out with King John, were real-life outlaws whose stories contributed to the romantic archetype.

Surviving Outside the Bounds of Society

Life for a real outlaw was not one of merry feasts and jovial camaraderie. It was a bleak, desperate struggle for survival.

Stripped of home and income, outlaws had to live off the land. This meant poaching game—itself a serious crime, especially in a royal forest—and foraging for whatever they could find. Robbery was often a necessity, but it was a high-risk game. Outlaws usually targeted travelers on remote roads, not to “give to the poor”, but to feed themselves. Survival depended on avoiding settlements and the people who lived in them.

The isolation was as much a threat as starvation or capture. Outlaws were cut off from their families, their faith, and their communities. They were damned in the next life as well as this one, as they could not receive sacraments or be buried in consecrated ground. Winter was a particularly brutal test, forcing many to risk seeking shelter, where they were most vulnerable to being recognized and betrayed.

Was There a Way Back? The King’s Mercy

Despite its finality, outlawry was not always a life sentence. A path back into society existed, but it was a narrow one: the King’s Pardon.

An outlaw, or their family on their behalf, could petition the Crown for mercy. A pardon was an act of grace, not a right, but it could be granted for several reasons:

- Military Service: Kings in constant need of skilled soldiers were often willing to pardon outlaws with martial experience in exchange for service in their armies, particularly for campaigns abroad.

- Payment: A wealthy or well-connected family could sometimes purchase a pardon for a substantial fine.

- A Flaw in the Process: If it could be proven that there was a legal error in the original outlawry proceedings, the sentence could be reversed.

If a pardon was granted, the outlaw would undergo a process of “inlawing”, restoring their legal status and rights. They could return home, but the stigma often remained. They were a living reminder of the king’s power—both to cast out and to draw back in.

Ultimately, outlawry was one of medieval society’s most potent instruments of power. It defined the absolute necessity of law and community by showing the terrifying void that existed outside of it. The romantic legend of the outlaw endures, but the history reminds us that for those declared a “wolf’s head”, life was anything but a merry adventure.