Imagine a world without a single glowing digital display, ticking bedside alarm, or even the familiar chime of a town clock tower. Imagine the deep, profound blackness of a medieval night, broken only by moonlight or the flicker of a candle. In this silent, dark world, how did a community dedicated to a strict schedule of prayer know when to rise for their most important duty—the pre-dawn service of Vigils?

For centuries, the sun was humanity’s great timekeeper. Its rise, meridian, and fall dictated the rhythm of work, meals, and rest. But the sun, of course, offered no help in the dead of night. The answer for medieval monks lay not in the sky, but in the steady, patient, and relentless drip of water. They relied on an ancient device, refined into a marvel of medieval engineering: the clepsydra, or water clock.

The Divine Schedule and the Problem of Night

Life in a medieval monastery revolved around the Opus Dei, or “Work of God”—a cycle of eight daily prayer services known as the canonical hours. Prescribed by the 6th-century Rule of Saint Benedict, this schedule was the structural and spiritual backbone of monasticism. It included Lauds (at dawn), Prime (early morning), Terce, Sext, and None (during the day), Vespers (at sunset), and Compline (before bed).

The most challenging, however, was Vigils (or Matins), a long service of psalms and readings held in the hours after midnight. Waking an entire community of monks at the correct time—say, 2 AM—in complete darkness was a serious logistical problem. A designated monk could be tasked with staying awake all night to watch the stars, but this was unreliable on cloudy nights and exhausting for the individual. What was needed was a dependable, automatic alarm, an artificial rooster that would crow on schedule, every single night.

An Ancient Idea Reborn

The water clock was not a medieval invention. Its origins stretch back to ancient Egypt and Babylon. The simplest form—a bowl with a hole in the bottom—was used for thousands of years. As water drained out, marks on the inside of the bowl would indicate the passing of time.

However, these simple outflow clocks had a fundamental flaw. As the water level in the vessel dropped, the water pressure decreased, causing the flow to slow down. The first hour would pass much faster than the last. The Greeks and Romans, most notably the inventor Ctesibius of Alexandria in the 3rd century BCE, developed far more sophisticated versions to solve this problem. It was this technological inheritance that medieval engineers, particularly within the resourceful world of the monastery, adapted and perfected.

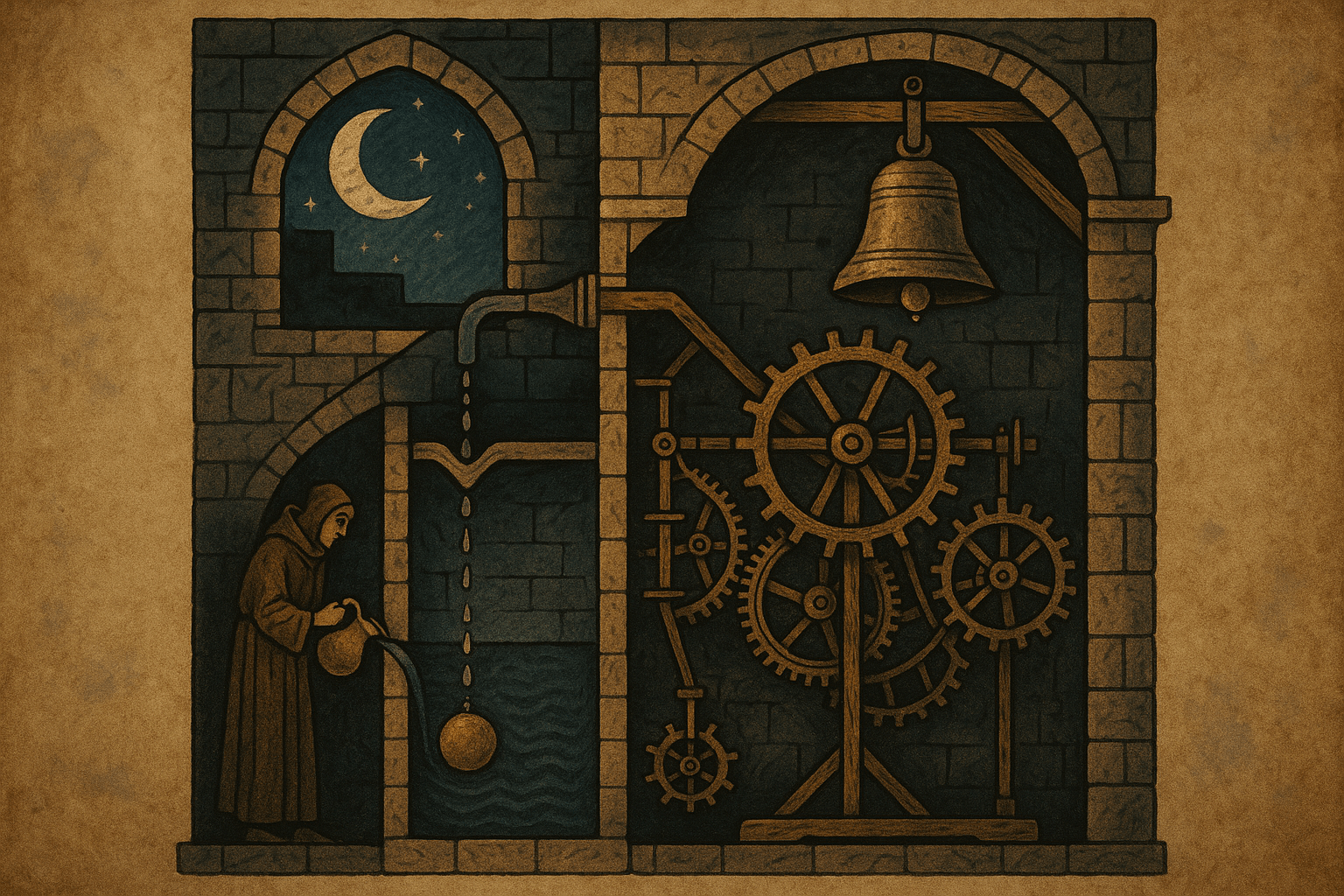

How to Build a Better Timepiece: The Medieval Clepsydra

A medieval monastic water clock was a far cry from a simple dripping bucket. Its design was a testament to a deep understanding of basic physics, designed for one primary goal: accuracy.

The key innovation was creating a constant, unvarying flow of water. Here’s how they did it:

- The Reservoir: At the top was a large reservoir, filled with water.

- The Regulating Tank: Water flowed from the reservoir into a smaller, secondary tank below it. This tank had an overflow pipe or spout. Once the water reached the level of the overflow, any excess water would simply drain away. This clever trick ensured that the water in this regulating tank remained at a constant level, and therefore, at a constant pressure.

- The Drip: From the bottom of this regulating tank, a small nozzle released water drop by drop, or in a tiny, steady stream. Because the pressure above it was always the same, this flow rate was reliably constant.

- The Measuring Cylinder: The drops fell into a final, larger cylinder below. Inside this cylinder was a float—often a hollow piece of wood or metal. As the water level slowly and steadily rose, so did the float.

A pointer attached to this float would then move up along a marked scale, indicating the passage of the hours through the long, silent night.

From Silent Marker to Ringing Alarm

Tracking the time was one thing, but waking a sleeping monastery was another. The true genius of the monastic water clock was its ability to be weaponized as an alarm. The monks devised ingenious trip mechanisms that transformed the silent rise of the float into the loud clang of a bell.

The designs varied, but the principle was often the same. As the float reached a predetermined height for the appointed hour of Vigils, it would trigger a chain reaction:

- The rising float might push up on a small lever.

- This lever would knock away a pin or a catch holding a heavy weight.

- With its catch released, the weight would fall, pulling a rope with it.

- The rope, in turn, would be connected to the clapper of a bell or a series of bells, yanking it and sounding a loud, insistent alarm that echoed through the cold stone dormitories and cloisters.

These were, in essence, the world’s first programmable alarm clocks. By adjusting the trip mechanism, the monks could set their “alarm” for the correct time, which would change depending on the season and the time of sunrise. Celebrated scholars and churchmen like Gerbert of Aurillac (who later became Pope Sylvester II) in the 10th century were renowned for their skill in designing such complex clocks, which seemed like magic to a largely illiterate populace.

The Challenges of Keeping Time with Water

For all their ingenuity, clepsydras were high-maintenance devices. The monk in charge of the clock, often the sacristan, had a vital and demanding job. The clock’s greatest enemy was the cold. In the unheated stone churches and monasteries of a Northern European winter, the water could easily freeze, stopping the clock and potentially cracking the vessels. Monks placed their clocks in protected interior rooms or tried to insulate them, but it was a constant battle.

Furthermore, any dust, sediment, or algae in the water could clog the tiny nozzle that regulated the flow, rendering the clock inaccurate. The entire system had to be regularly drained, cleaned, and refilled, a daily ritual essential for the spiritual rhythm of the community.

The Dawn of a New Time

For centuries, the dripping clepsydra was the most advanced timekeeping technology in Europe. But by the late 13th and early 14th centuries, a revolutionary new invention appeared: the mechanical clock. Driven by weights and regulated by a mechanism called the verge and foliot escapement, these new clocks were more accurate, more robust, and less susceptible to the elements. They ticked instead of dripping, marking time with a metallic heartbeat that would soon come to define the sound of a modernizing world.

The water clock’s reign came to an end. Yet, for a millennium, it was the silent, tireless engine that brought order to the darkness. It was a symbol of human ingenuity, born from a spiritual necessity, reminding us that long before the digital age, we found a way to make water, gravity, and wood do the essential work of calling the faithful to prayer, time after dark.