Imagine London in the late summer of 1854. It’s a city of unprecedented growth and industrial might, but also a city of suffocating smells and a creeping, invisible dread. The dread had a name: cholera. Known as the “Blue Death” for the chilling cyanotic hue it gave its victims’ skin, cholera was a terrifying and swift killer. Within hours, a perfectly healthy person could be reduced to a dehydrated shell, dying from violent vomiting and diarrhea. And in August of 1854, it was tearing through the narrow, crowded streets of the Soho district with terrifying speed.

The Reign of the “Bad Air”

The leading medical minds of the day were convinced they knew the enemy. They called it “miasma”—a foul, toxic fog of decaying organic matter that they believed rose from the River Thames, from open sewers, and from the general filth of the overpopulated city. To the Victorian medical establishment, disease was a pestilence you breathed in. It made a grim kind of sense; London stank, and where the smell was worst, disease often seemed to follow.

The Board of Health, following this theory, issued recommendations that were logical but ultimately useless. They advised citizens to clean up garbage and even suggested that burning fragrant materials could purify the air. But as the death toll in Soho climbed, it became clear the miasma theory couldn’t explain the ferocity and concentration of this particular outbreak.

Enter our hero: a quiet and methodical physician named Dr. John Snow. A pioneer in the field of anesthesiology (he had administered chloroform to Queen Victoria during childbirth), Snow was a skeptic by nature. For years, he had harbored a radical, almost heretical idea. He believed cholera wasn’t in the air. It was in the water.

A Radical Hypothesis

Snow reasoned that if cholera were airborne, its symptoms would begin in the respiratory system, like a cold or influenza. Instead, cholera’s brutal assault was centered entirely on the digestive tract. This, he argued, pointed to something that was being ingested, not inhaled. His “germ” theory—the idea that a living, self-replicating organism was causing the illness—was dismissed by most of his peers as fanciful nonsense.

The tragic Soho outbreak, however, presented Snow with what he grimly called his “Grand Experiment.” This neighborhood nightmare was a chance to finally prove his theory. Instead of pontificating from an armchair, Snow took to the streets.

The Detective Work Begins: Data and a Dot Map

In what is now celebrated as the birth of modern epidemiology, John Snow became a medical detective. He went door-to-door in Soho, speaking to the families of the victims. He was methodical, calm, and deeply persistent. His most important question was simple: “Where do you get your water?”

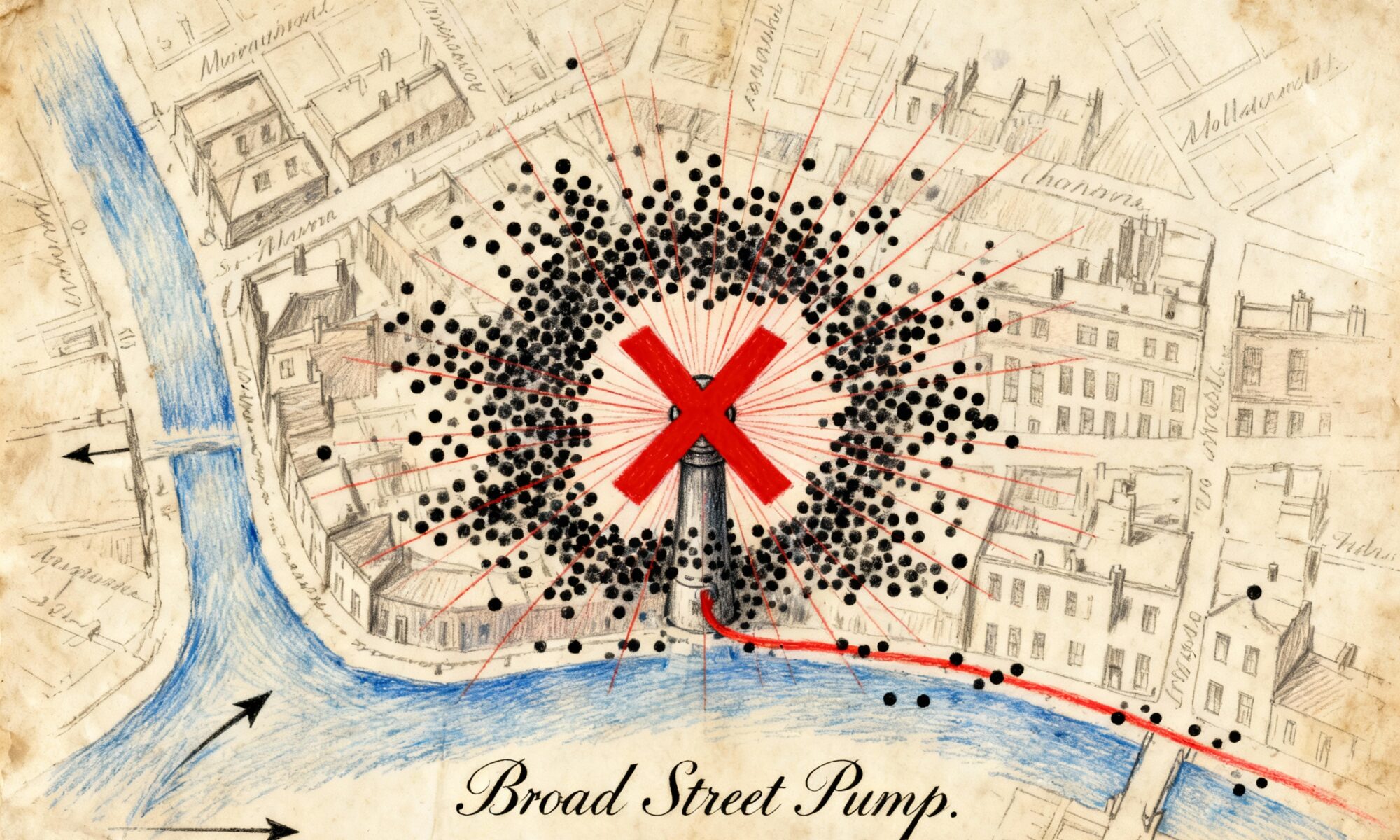

At the time, many Londoners drew water from public pumps scattered throughout the city. Snow began to document the source of water for every household that had suffered a death. He then took his data and did something revolutionary: he plotted it on a map.

What he created was more than just a map; it was a data visualization masterpiece, one of the first of its kind. He marked the location of each cholera death with a small black bar at the corresponding address. As he meticulously added each fatality, a terrifying pattern emerged. The black bars swarmed, like iron filings to a magnet, around a single point: the public water pump on Broad Street (now Broadwick Street). The further a home was from that pump, the fewer deaths there were. The visual evidence was undeniable—the pump was the epicenter.

John Snow’s original map, where each black bar represents a cholera death. The cluster around the pump in the center is unmistakable.

The Anomalies That Proved the Rule

But great scientific inquiry isn’t just about finding patterns; it’s about explaining the exceptions. Snow’s genius shone brightest when he investigated the anomalies—the cases that didn’t seem to fit his theory.

- The Brewery: Right on Broad Street, in the heart of the outbreak, stood a brewery. Yet, not a single one of its 70 workers had contracted cholera. Why? Snow investigated and found the answer was simple: the brewery gave its workers a daily allowance of beer. They never drank water from the nearby pump. They also had their own private well on-site.

- The Workhouse: Nearby was a workhouse with over 500 inmates, a place that should have been a tinderbox for disease. Yet it had suffered only five deaths. Snow discovered the workhouse had its own private water supply and did not use the Broad Street pump.

- The Distant Deaths: The most compelling piece of evidence came from outside Soho entirely. Snow learned of a widow who had died of cholera in Hampstead, several miles away. Her case seemed to completely contradict his findings. Undeterred, Snow interviewed her son. He learned that the widow had once lived in Soho and had developed a fondness for the taste of the water from the Broad Street pump. She liked it so much that she had a servant fetch a large bottle of it for her every day. The water she drank on the day before she fell ill came from the contaminated source. It was the smoking gun.

Taking the Handle Off the Pump

Armed with his damning map and detailed accounts, Snow presented his evidence to the local parish Board of Guardians on September 7, 1854. While still skeptical of his waterborne theory and clinging to the idea of a miasma lurking in a faulty sewer, they were alarmed enough by his data to act. In a moment that would become legendary in the annals of public health, they agreed to a simple, decisive action: on September 8, the handle of the Broad Street pump was removed, preventing anyone from drawing more water.

While the outbreak had likely already peaked by this point, the removal of the handle was a monumental symbolic victory. It was an intervention based not on superstition or prevailing wisdom, but on data, mapping, and logical deduction.

Later investigations of the pump well discovered the source of the contamination. The well’s brick lining had decayed, and it was being infiltrated by a leaking cesspool just three feet away. Within that cesspool were the soiled diapers of an infant who had contracted cholera from another source, tragically becoming “patient zero” for the Broad Street outbreak.

The Legacy of John Snow

John Snow’s theory was not accepted overnight. The medical establishment, led by influential figures like William Farr, continued to champion the miasma theory for years. It wouldn’t be until decades later, when Robert Koch identified the bacterium Vibrio cholerae in 1883, that the germ theory of disease was fully vindicated.

Yet, the story of John Snow and the Broad Street pump remains the foundational legend of modern epidemiology. He demonstrated that by systematically collecting and analyzing data, one could trace the origins of an epidemic and take effective action to stop its spread. His methods—shoe-leather investigation, data mapping, and hypothesis testing—are the bedrock of public health to this day.

Today, a replica pump (without a handle) stands on Broadwick Street, with a nearby pub named “The John Snow” in his honor. It serves as a monument to a man whose brilliant and persistent work saved countless lives and gave humanity a powerful new weapon in the fight against disease: information.