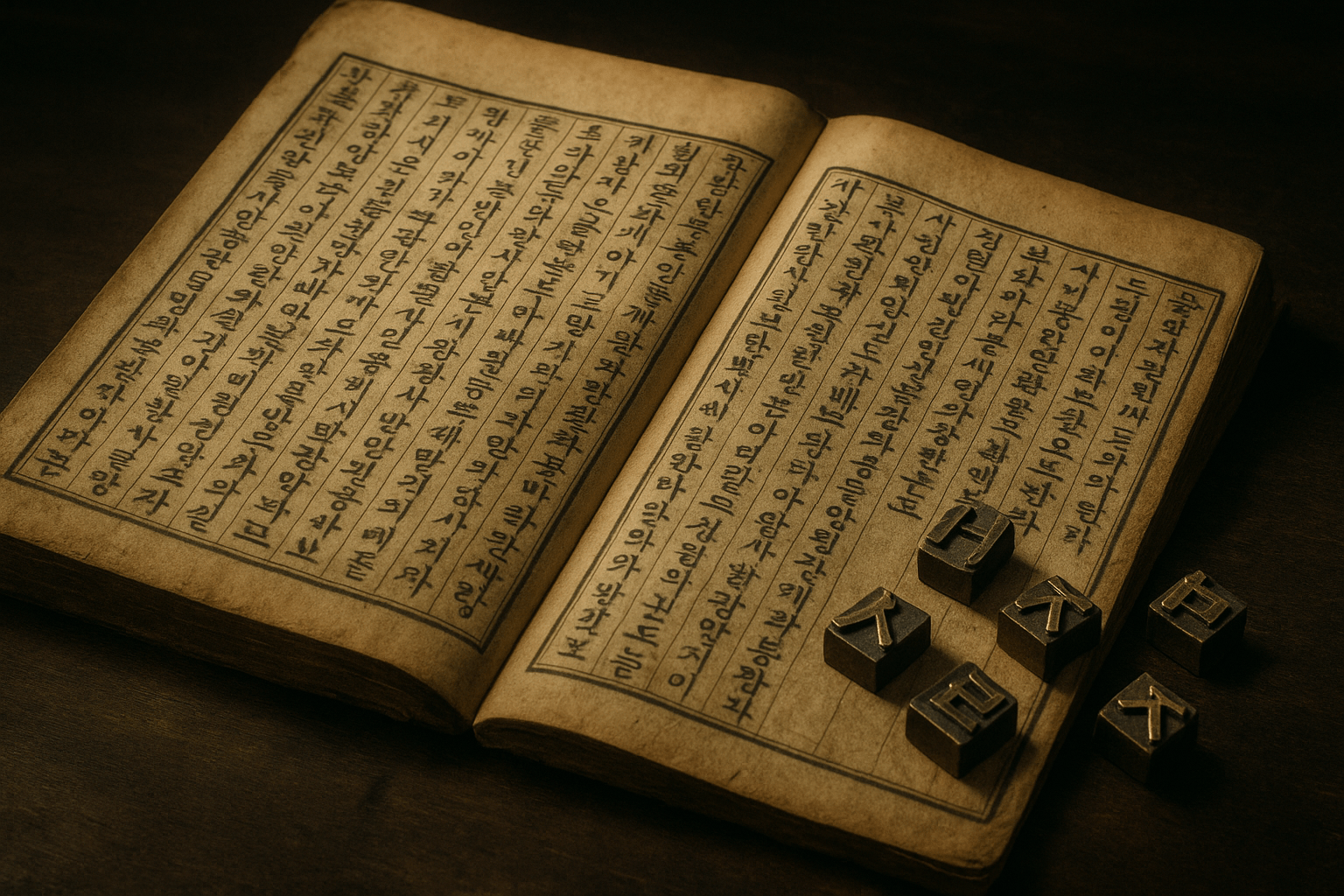

Printed in 1377—a full 78 years before Johannes Gutenberg’s famous Bible—Jikji is the world’s oldest surviving book printed using movable metal type. Its existence doesn’t just shift a date on a timeline; it redraws the map of technological innovation and forces us to look beyond Europe to understand one of humanity’s most important inventions.

What Exactly is Jikji?

The book’s full title is a mouthful: “Baegun hwasang chorok buljo jikji simche yojeol.” This translates to “The Venerable Monk Baegun’s Anthology of the Great Buddhist Priests’ Teachings on Identification of the Buddha’s Spirit by the Practice of Seon.” For short, it’s called Jikji, which means “pointing directly.” The title itself reflects its contents: a collection of excerpts, sermons, and teachings from various Buddhist masters, compiled by the monk Baegun Gyeonghan (1298–1374).

The core message of Jikji is central to Seon (Zen) Buddhism: that one can attain enlightenment by looking directly into the essence of the mind. It’s not a narrative or a single doctrinal work, but a curated guide for meditation and spiritual understanding. The surviving volume, currently housed at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (National Library of France) in Paris, is the second and final volume of the original two-part set. The first volume remains lost to history.

A Crucible of Innovation: The Goryeo Dynasty

To understand why this breakthrough happened in 14th-century Korea, we must look at the historical context of the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392). This was a period of immense cultural and artistic achievement, but also of significant external threat, primarily from the neighboring Mongol Empire (Yuan Dynasty).

Buddhism was the state religion, and there was a high demand for religious texts for study and worship. Goryeo was already a world leader in printing, having perfected the art of woodblock printing. The monumental Tripitaka Koreana, a complete collection of Buddhist scriptures carved onto more than 81,000 woodblocks in the 13th century, stands as a testament to their mastery. These woodblocks, still preserved today, could produce beautiful prints but had a major drawback: they were inflexible. Each block was a static image of a full page, and a single mistake meant re-carving the entire block. Moreover, storing tens of thousands of bulky woodblocks was a tremendous challenge.

Constant invasions created a sense of urgency. Temples and their vast wooden libraries were vulnerable to fire and destruction. The Goryeo court and its Buddhist monks logically sought a more durable, efficient, and reusable method for preserving and disseminating their sacred knowledge. Movable metal type was the answer.

From Carved Wood to Cast Metal

The process developed by Goryeo artisans was ingenious. While the exact methods involved some proprietary knowledge, historians have pieced together the likely steps:

- Character Carving: First, a master calligrapher would write the characters, which were then painstakingly carved onto pieces of wood to create a master copy of each character.

- Mold Creation: These wooden characters were pressed into a bed of fine, wet clay or sand, creating a negative mold.

- Casting: Molten bronze was poured into the molds. Once cooled, the result was a set of individual metal characters, each a mirror image of the original.

- Typesetting: These metal characters were then arranged in a rectangular tray, set in wax to hold them in place, to form the text of a full page.

- Printing: The typeset plate was inked, a sheet of paper (hanji, a high-quality Korean paper) was laid over it, and pressure was applied to create the print.

The beauty of this system was its reusability. After printing the desired number of copies of a page, the type could be broken up and rearranged to create a completely new page. This was a revolutionary leap beyond the single-use nature of a woodblock.

The Colophon: A Birth Certificate in Ink

We know Jikji was printed in 1377 with such certainty because of the book itself. The last page contains a colophon—a publisher’s inscription—that details its creation. It states clearly that the book was printed “in the 7th month of the 3rd year of King U [1377] at Heungdeok temple outside Cheongju-mok, using movable metal type.”

This inscription is the textual “smoking gun.” It credits the disciples of Monk Baegun, including the priestess Myodeok, for their sponsorship and effort in carrying out their master’s wish to see the teachings widely distributed. The book was born not in a royal printing office, but through the devotion of monks and nuns at a provincial temple.

A Long Sleep and a Grand Reawakening

So how did this Korean national treasure end up in Paris? The story involves one of the first French diplomats to Korea, Victor Collin de Plancy. Stationed in Seoul in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, he was an avid collector of Korean art and books. He acquired the Jikji as part of his collection and brought it back to France, where it was eventually donated to the Bibliothèque nationale.

There it sat in relative obscurity for decades, its true significance unknown to the wider world. Its reawakening came thanks to Dr. Park Byeong-seon, a Korean historian and librarian who began working at the Bibliothèque nationale in 1967. While cataloging the Asian collection, she stumbled upon the Jikji. With her deep knowledge of Chinese characters and Korean history, she recognized the colophon and understood its earth-shattering implication. She spent years meticulously verifying its authenticity and proving that it predated Gutenberg’s work.

In 1972, during the “International Book Year” exhibition in Paris, Jikji was finally presented to the world as the oldest extant book printed with movable metal type. The quiet document from a forgotten temple was suddenly an international sensation.

A UNESCO Memory of the World

In 2001, UNESCO officially confirmed Jikji’s status by inscribing it on the Memory of the World Register. This program recognizes documentary heritage of universal value and significance. Jikji’s inclusion was a global acknowledgment of its place in human history—not just as a Korean achievement, but as a milestone for all of humanity.

Jikji’s story doesn’t diminish the accomplishments of Gutenberg. His printing press, oil-based ink, and lead-tin-antimony alloy for type were revolutionary in their own right and sparked a printing revolution that transformed Europe. But Jikji reminds us that innovation is not a linear path originating from a single point. It is a branching river, with currents of genius flowing in different parts of the world at different times.

The journey of Jikji—from a Goryeo temple to a Parisian library, from a monk’s teachings to a UNESCO treasure—is a powerful lesson. It teaches us that history is full of hidden chapters, waiting for dedicated eyes to rediscover them and share their incredible stories with the world.