Imagine, for a moment, a world without chocolate. No decadent desserts, no comforting cups of hot cocoa, no simple bar to brighten a tough day. It’s a bleak picture, yet for most of human history, this was reality for everyone outside of a specific region in Mesoamerica. The story of how chocolate traveled from the New World to the Old is a fascinating tale of conquest, culture clash, royal secrets, and delicious innovation.

A Drink of Gods and Warriors: Cacao in the Aztec Empire

Long before Europeans ever dreamed of chocolate, the civilizations of Mesoamerica, including the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec, had been cultivating cacao for millennia. For the Aztecs in the 15th and 16th centuries, the beans of the Theobroma cacao tree (a name that literally means “food of the gods”) were more valuable than gold. In fact, they were used as a form of currency—a single turkey could be bought for 100 beans, and a canoe-full of fresh water for just one.

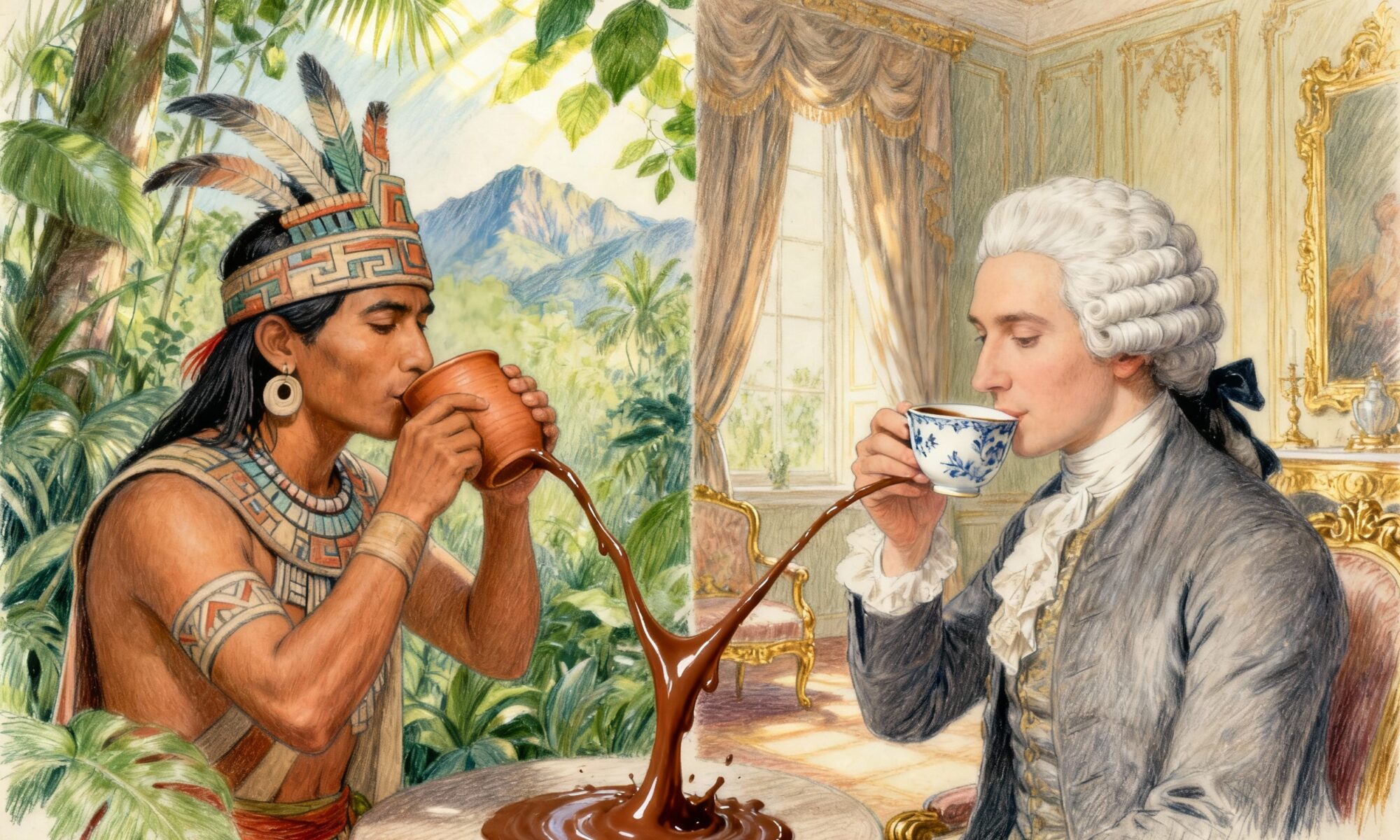

But its primary value was cultural and ceremonial. The Aztecs consumed a beverage they called xocolātl (pronounced sho-ko-la-tl), which translates to “bitter water.” And bitter it was. To create it, cacao beans were roasted, ground into a paste, and then mixed with water, maize, chili peppers, and other spices. The mixture was poured from a height to create a thick, bitter, and often spicy froth on top. This wasn’t a sweet treat; it was a powerful, stimulating drink reserved for the elite—warriors, priests, and nobility. The Aztec emperor, Montezuma II, was said to drink dozens of goblets of xocolātl a day to boost his energy and libido.

The Spanish Encounter: A Bitter First Impression

When Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his men arrived in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán in 1519, they were introduced to this strange, frothy beverage. Their initial reaction was not one of delight. Accustomed to the sweet wines and flavors of Europe, the Spanish found the spicy, bitter xocolātl to be an acquired taste, with one Spaniard describing it as “a bitter drink for pigs.”

However, Cortés was a shrewd observer. He noted the immense value the Aztecs placed on cacao beans and the reverence with which they consumed the drink. He understood that while the taste was foreign, the bean itself was a source of wealth and power. He saw its potential not just as a foodstuff, but as a commodity. In his letters back to King Charles V of Spain, Cortés reported on the “money” that grew on trees. In 1528, he returned to Spain not just with treasure, but with a large shipment of cacao beans and the equipment needed to prepare the drink.

Spain’s Sweet Secret: The Transformation of Xocolātl

Back in Spain, xocolātl underwent a radical transformation. The Spanish court and, most notably, the monks in their monasteries, began to experiment with the recipe. Realizing the bitterness was the main obstacle, they made a revolutionary change: they added sugar.

The chili peppers were swapped out for sweeter spices familiar to the European palate, like cinnamon, nutmeg, and vanilla (another New World discovery). They also began serving the drink hot. The result was a rich, sweet, and aromatic beverage that was utterly intoxicating. This new version, now simply called “chocolate”, became an instant sensation among the Spanish aristocracy.

For nearly a century, Spain successfully kept chocolate as its own delicious secret. It was a symbol of immense wealth and status, enjoyed behind the closed doors of royal palaces and the quiet cloisters of monasteries. The high cost of importing both cacao and sugar kept it firmly in the hands of the rich, making it a beverage of unparalleled luxury.

Chocolate Conquers Europe: A Royal Marriage and Spreading Secrets

A secret this good couldn’t be kept forever. The dam of Spanish exclusivity finally broke thanks to royal diplomacy and marriage. In 1615, Anne of Austria, the daughter of the Spanish King Philip III, married King Louis XIII of France. When she moved to the French court, she brought her precious cacao and the custom of drinking chocolate with her.

From that moment on, chocolate mania swept across Europe’s upper classes:

- France: The French court fell in love with it, and Paris soon had its own elite chocolate shops.

- England: Chocolate arrived in London in the 1650s, leading to the establishment of “chocolate houses.” These establishments, similar to coffee houses, became fashionable social hubs for the wealthy to conduct business, gossip, and gamble while sipping the exotic new drink.

- Italy and Beyond: Italian traders and clerics helped spread chocolate’s popularity throughout the rest of Europe, with each country adding its own unique twist to the recipe.

Despite its spread, chocolate remained an expensive luxury, a status symbol accessible only to the wealthy. It would take the Industrial Revolution to change that.

From Elite Beverage to Everyday Bar

The 19th century brought a series of technological breakthroughs that democratized chocolate. In 1828, a Dutch chemist named Coenraad van Houten invented the cocoa press, a machine that could separate the natural cocoa butter from the ground cacao beans. This left a fine powder—cocoa powder—that was easier to mix with liquids and also provided the crucial ingredient for solid chocolate.

In 1847, the British company Fry’s created what is widely considered the first mass-produced chocolate bar by mixing cocoa powder, sugar, and melted cocoa butter. The journey was almost complete. Finally, in 1875, Swiss chocolatier Daniel Peter added powdered milk (an invention by his neighbor, Henri Nestlé) to the mixture, creating the first milk chocolate bar and sealing the fate of chocolate as a global obsession.

From a sacred, bitter drink for Aztec emperors to a treasured secret of the Spanish court and, finally, to the everyday treat in our hands, chocolate’s journey is a microcosm of world history. It’s a story of exploration, conquest, and cultural exchange—a delicious reminder of how a simple bean transformed our world.