The First Reds: Ochre and Earth

Red’s story begins not in a king’s court, but in the dust of the earth. For our earliest ancestors, red was one of the first pigments available. Red ochre, a clay rich in iron oxide, was humanity’s first crayon. As far back as 100,000 years ago, early humans used this rust-colored earth for body paint and, most famously, in the stunning cave paintings of Lascaux and Altamira. These artworks weren’t merely decorative; they were likely tied to ritual and survival, depicting the lifeblood of the hunt.

This deep connection to blood—the essence of life and death—cemented red’s power. Many ancient cultures used red ochre in funerary rites, dusting the bones of the deceased in the pigment. This practice, seen from Europe to Australia, suggests a belief that the color could magically restore life or protect the spirit in the afterlife. From its very origin, red was the color of the profound.

The Exclusive Reds of the Ancient World

As civilizations rose, so did the desire for a red that was more brilliant and lasting than simple ochre. Rarity created value, and the most vibrant reds became the ultimate symbols of wealth and status. The Romans had Tyrian Purple, a dye made from thousands of putrefied sea snails that could range from deep crimson to violet. A senator’s toga was marked with a Tyrian stripe, a privilege denied to ordinary citizens.

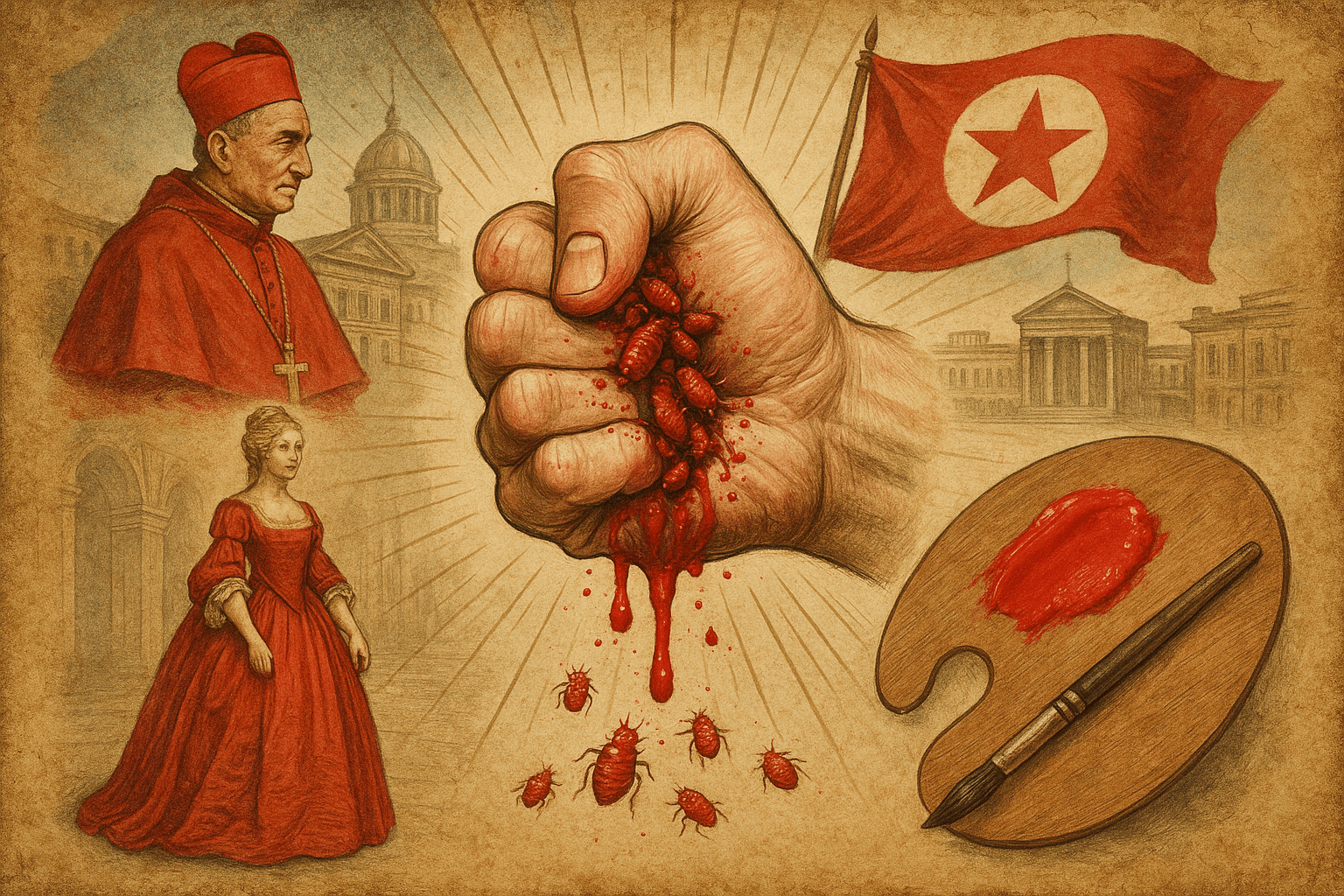

Before the discovery of the Americas, the most prized red in Europe came from a tiny insect, Kermes vermilio. These insects, which live on oak trees in the Mediterranean, were harvested, dried, and crushed to produce a brilliant scarlet. Known as “crimson” from the Arabic word qirmiz, the dye was so expensive that its use was reserved for the highest echelons of society. The Catholic Church adopted it for the robes of its cardinals, symbolizing their willingness to shed their blood for their faith. For centuries, the finest red cloth was literally worth its weight in gold.

A New World of Red: The Cochineal Revolution

Everything changed in the 16th century when Spanish conquistadors stumbled upon the Aztec and Incan empires. Amidst the gold and silver, they found something almost as precious: a new source of red that made European kermes look dull and faded. This was the color produced by the cochineal insect (Dactylopius coccus), a tiny parasite that fed on prickly pear cacti.

When dried and crushed, these insects yielded a carminic acid of unparalleled intensity and permanence. This was “the perfect red”, and the Spanish immediately recognized its value. They established a monopoly on the trade, and for over two centuries, cochineal became the New World’s second most-valuable export after silver. The source of the dye was a fiercely guarded secret; many European artisans believed it came from a plant seed, not an insect.

This American red flooded Europe, coloring the world of the powerful. It was the red used by artists like Titian, Rembrandt, and Van Dyck to bring life to their portraits. Most famously, it was the dye used to create the iconic uniforms of the British Army’s “Redcoats”, a symbol of imperial might seen across the globe. The very symbol of British power was, ironically, funded by Spain and farmed in Mexico.

The Color of Sin and Revolution

While red clothed kings and cardinals, it also carried a darker, more rebellious connotation. In Christianity, red was not only the color of Christ’s blood and Pentecostal fire, but also the color of the Devil and the Whore of Babylon. This duality made it a powerful symbol of moral transgression, most famously embodied by Hester Prynne’s The Scarlet Letter.

This association with defiance found a political voice during the French Revolution. In 1789, revolutionaries adopted the red “Phrygian cap” as a symbol of liberty from oppression. Though the red flag was initially hoisted by the authorities as a sign of martial law, it was quickly co-opted by the Jacobins and other radicals to symbolize “the blood of angry men”—a willingness to die for their cause. The color of monarchy became the color of the people’s fury.

This revolutionary flame was carried forward. In 1871, the Paris Commune proudly flew the red flag. But its most enduring political legacy was cemented in 1917 with the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. The “Reds” (Bolsheviks) fought the “Whites” (counter-revolutionaries), and upon their victory, the red flag, adorned with a hammer and sickle, became the symbol of the Soviet Union. For the rest of the 20th century, red was the international color of Communism and socialism, a banner of world-altering ideology that stood in direct opposition to the old world of kings and cardinals it once represented.

The Modern Red

Today, red’s complex history echoes in our daily lives. The development of synthetic dyes in the 19th century made vibrant reds accessible to everyone, but the color never lost its power. Its ancient link to danger and life/death makes it the universal color for stop signs, emergency lights, and warning labels. Its history of luxury and desire lives on in the gleam of a Ferrari, the allure of a red dress, and the exclusive, coveted soles of Christian Louboutin shoes. And, of course, its connection to the heart makes it the undisputed color of love and passion on Valentine’s Day.

From the dusty ochre of a prehistoric cave to the crimson dye of an Aztec market, from a cardinal’s robes to a revolutionary’s flag, the color red has never been just a shade. It is a historical record, chronicling our deepest instincts and our most dramatic transformations.