What Was This “Liquid Fire”?

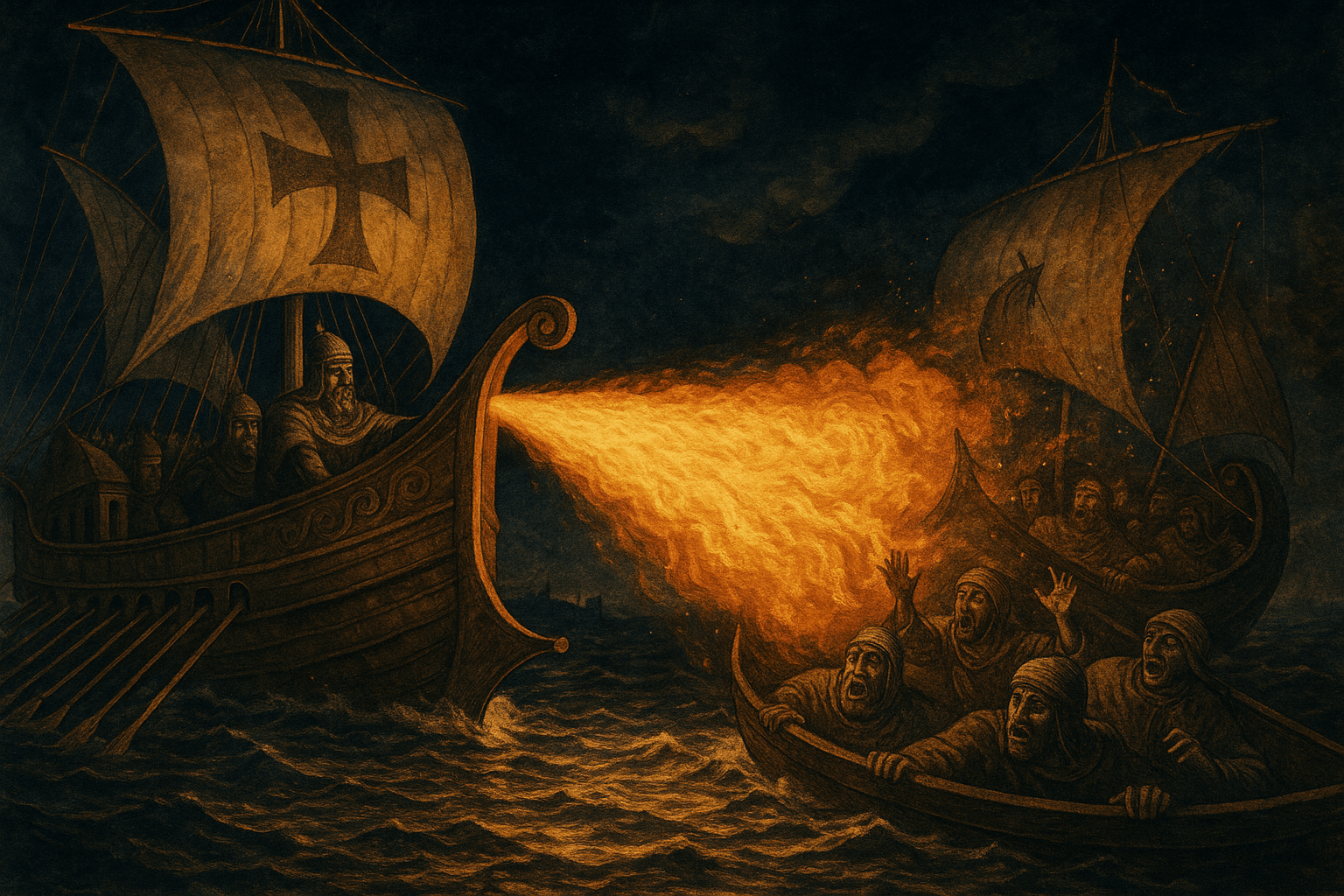

For over 700 years, Greek Fire was the Byzantine Empire’s most fearsome and decisive weapon. It was an incendiary substance, a sort of primitive napalm, with properties that struck terror into the hearts of their enemies. Unlike ordinary fire, it was famously said to burn on water and could only be extinguished by a few specific substances, like sand, vinegar, or, allegedly, old urine. It was a sticky, adhesive liquid that clung to ships and flesh, ensuring maximum destruction.

The psychological impact was as potent as the physical damage. To an enemy sailor in the 7th or 8th century, seeing fire itself being weaponized and shot across the sea was like witnessing a dark and demonic magic. This fear gave the outnumbered Byzantine navy a critical edge, allowing them to repeatedly triumph against overwhelming odds.

The Ultimate State Secret

One of the most tantalizing aspects of Greek Fire is that its exact chemical composition remains a mystery. The formula was a jealously guarded state secret, known only to a handful of trusted individuals within the Byzantine administration. The knowledge was passed down through generations of a single family, the Kallinikos, named after its supposed inventor, a refugee from Syria. Revealing the formula was an act of high treason, and the Byzantines guarded it so well that it was eventually lost to history.

Despite the secrecy, historical accounts and modern chemical analysis have given us educated guesses about its ingredients. The mixture was almost certainly petroleum-based, likely using a light crude oil called naphtha. Other probable ingredients included:

- Pine Resin: This would make the mixture sticky, helping it adhere to enemy ships and personnel.

- Sulfur: Adding sulfur would create suffocating and poisonous fumes upon ignition, adding another layer of terror to the weapon.

- Quicklime: Some theories suggest that quicklime (calcium oxide) was a key component. When quicklime comes into contact with water, it produces a violent exothermic reaction, generating immense heat. This could have been the secret to its self-ignition or its ability to “burn on water.”

The combination of a flammable fuel (naphtha), a sticky agent (resin), and a potential self-igniting compound (quicklime) would create the devastating weapon described in historical chronicles.

Unleashing the Inferno: The Siphon and the Dromon

The primary method for deploying Greek Fire was a remarkable piece of proto-industrial technology: the siphon. This device was a large bronze tube, often decorated to look like a roaring lion or dragon’s head, mounted on the prow of Byzantine warships called dromons.

The process was complex and incredibly dangerous for its operators. The liquid mixture was heated in a sealed cauldron, building up immense pressure. A hand-pump, similar to a blacksmith’s bellows, would force the superheated, pressurized liquid through the siphon. As the stream of fire shot out, it was likely ignited by a small flame at the nozzle. The result was an ancient flamethrower, capable of blasting enemy ships from a safe distance.

The historian and emperor Leo VI the Wise described the terrifying effect: “…with a clap of thunder and a great flash of light, it would set the enemy ships on fire.” Beyond the large ship-mounted siphons, the Byzantines also developed hand-held versions called cheirosiphons for use by marines in close-quarters combat, as well as clay grenades filled with the substance that could be thrown onto enemy decks.

Shield of the Empire: Greek Fire at War

The importance of Greek Fire to the survival of the Byzantine Empire cannot be overstated. It was the secret weapon that saved the capital on numerous occasions.

The most critical instances were the two great Arab sieges of Constantinople. During the first siege (674-678), the Umayyad Caliphate’s navy blockaded the city for years, but the Byzantine fleet, using Greek Fire, consistently burned their way through the blockades, eventually forcing a retreat. The second siege (717-718) was even more momentous. An enormous Muslim army and navy attempted to finally snuff out the Eastern Roman Empire. Again, Greek Fire turned the tide. The Byzantine navy methodically destroyed the Umayyad fleet, trapping their land army and leaving it to starve through a brutal winter. This victory was a turning point in history, halting the Caliphate’s advance into southeastern Europe and preserving Byzantium for another 700 years.

Later, in 941, the weapon was turned against a new foe from the north: the Rus’, fierce Viking descendants from Kiev. The chronicler Liutprand of Cremona, who witnessed the aftermath, wrote a vivid account:

“The Rus’, seeing the flames, jumped overboard, preferring to be drowned in the water rather than be burned alive in the fire. Some sank to the bottom, weighed down by the weight of their breastplates and helmets… The Greeks were victorious and returned to Constantinople in triumph.”

The Secret Lost

So what happened to this game-changing weapon? By the 15th century, it had vanished. Its decline was likely a gradual process tied to the decline of the empire itself. The most devastating blow came in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, when Western European crusaders sacked and occupied Constantinople. The immense institutional disruption, the destruction of libraries, and the slaughter of the imperial bureaucracy likely resulted in the permanent loss of the secret formula.

When the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II arrived to besiege Constantinople for the final time in 1453, the defenders no longer had their legendary liquid fire. The age of incendiary naval warfare was over, replaced by a new superweapon: gunpowder. The massive cannons Mehmed used to breach Constantinople’s fabled walls signaled the end of one era and the violent birth of another.

The legacy of Greek Fire, however, endures. It stands as a testament to Byzantine ingenuity, a weapon of both technological marvel and psychological terror that served as the shield of an empire for centuries, protecting a civilization and, in doing so, shaping the course of world history.