Close your eyes and imagine the quintessential flavour of the Roman Empire. You might picture wine, olive oil, or freshly baked bread. But the taste that truly defined the Roman world, from the legionary’s humble meal to the emperor’s lavish banquet, was something far more pungent, complex, and surprising: garum.

This fermented fish sauce was the ketchup, soy sauce, and Worcestershire sauce of its day, all rolled into one. It was a ubiquitous condiment, a critical trade commodity, and a multi-million sesterces industry built on what many today would wrinkle their noses at—fermented fish guts. But to dismiss it as “rotten fish sauce” is to miss the story of a sophisticated culinary and economic empire.

What Exactly Was Garum?

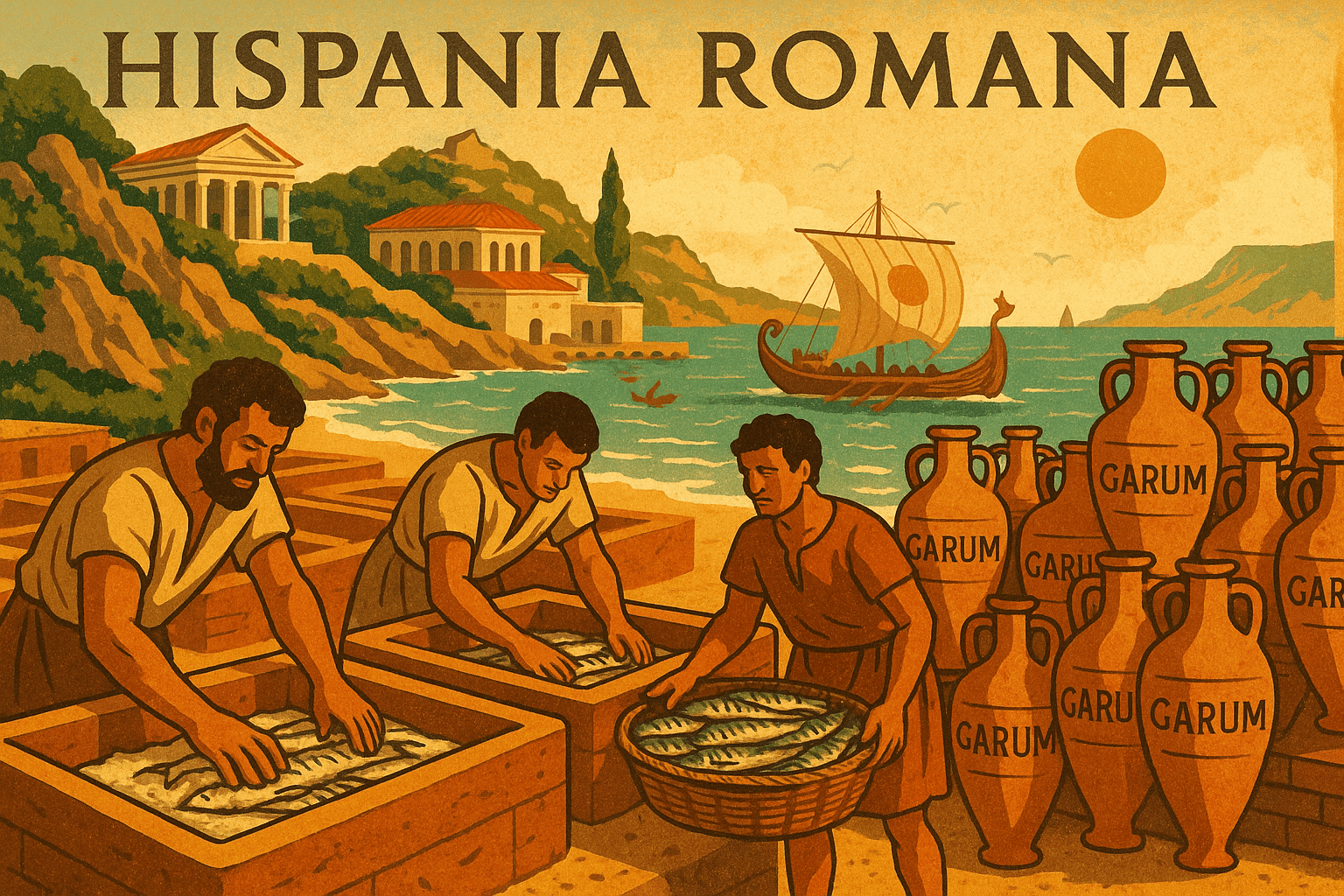

At its core, garum was the liquid product of fish fermentation. The process, however, was far more science than spoilage. Fishermen would take whole small fish like anchovies and sardines, or just the blood and viscera of larger fish like tuna and mackerel, and layer them in large vats or tanks called cetariae with salt. The ratio was crucial, typically one part salt to three parts fish.

The mixture was then left under the hot Mediterranean sun for several weeks to months. The high salt concentration prevented the growth of bacteria that cause rot. Instead, the fish’s own digestive enzymes initiated a process called autolysis, breaking down the proteins and tissues into amino acids. The result was a clear, amber-coloured liquid rich in glutamates—the chemical compound responsible for the savoury “umami” taste.

The final product wasn’t a single, uniform sauce. It existed in a wide range of qualities and prices:

- Garum: The general term, but often referred to the high-quality, first-press liquid skimmed from the top.

- Haimation: The most luxurious and expensive variety, made exclusively from the blood and guts of tuna. The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder wrote that two congii (about 1.7 gallons) of this top-tier sauce could cost 1,000 sesterces—the equivalent of a soldier’s pay for months.

- Liquamen: A term often used interchangeably with garum, but sometimes referring to a slightly lower-grade sauce made from whole fish.

- Allec: The thick, pasty sludge left at the bottom of the vats after the liquid was drained off. This was the cheapest version, sold to the poor and used to feed slaves. It was a caloric and salty paste that could make bland porridge more palatable.

While the production centres were notoriously smelly, the finished sauce was described as having a savoury, salty flavour, not a rotten one. Think of a more intense version of modern Southeast Asian fish sauces like Vietnam’s nước mắm or Thailand’s nam pla.

The Stink of Money: A Fermented Fortune

Garum production was no small-time cottage industry; it was a cornerstone of the Roman economy. Huge production facilities dotted the coastlines of the empire, particularly in Hispania Baetica (southern Spain), North Africa, and Sicily. The ruins of one of the largest garum factories can still be seen today at Baelo Claudia, near modern-day Tarifa, Spain. Its massive stone vats stand as a silent testament to the industrial scale of this enterprise.

The city of Pompeii was another major production hub. When Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE, it preserved garum shops, complete with their large storage jars (dolia) and specially designed transport containers called amphorae. One of the most successful producers in Pompeii was Aulus Umbricius Scaurus, whose personal mansion was decorated with mosaics depicting his own garum amphorae. His products, like “Flower of Garum”, were a famous brand across the empire.

These amphorae were the key to garum’s global reach. Sealed with cork and pitch, they were loaded onto merchant ships and transported throughout the Mediterranean and beyond, reaching as far as Britain and the frontiers of Germania. Painted labels on the jars, known as tituli picti, acted as branding, indicating the producer, the type of sauce, and its origin. For archaeologists, these labels provide an invaluable map of Roman trade routes and economic connections.

The army was one of the biggest consumers. Garum was a standard part of a Roman legionary’s rations. It provided essential salt to prevent dehydration and a powerful flavour boost to their simple diet of grains and vegetables, making it a crucial element of military logistics.

A Taste of Rome: From Kitchens to Medicine Cabinets

In the Roman kitchen, garum was indispensable. The famous Roman cookbook, De re coquinaria (attributed to Apicius), features garum in nearly every recipe. It was used much like salt today, but it also added a deep, savoury complexity that salt alone could not provide.

Romans would mix it with wine (oenogarum), vinegar (oxygarum), or oil (oleogarum) to create a variety of dipping sauces and dressings. It was drizzled over grilled meats, stirred into stews, and even used in some sweet dishes, where its saltiness would enhance the sweetness of fruits and honey, much like salted caramel today.

The type of garum you used was a potent status symbol. The wealthy elite would import the finest haimation from Spain, while a common tradesman might use a locally produced liquamen. For the vast majority of the urban poor, the sludgy allec smeared on bread was their only access to this imperial flavour.

Beyond the kitchen, Romans believed garum had medicinal properties. Pliny the Elder recommended it as a cure for dysentery, a treatment for animal bites, and a remedy for ulcers and skin conditions. While these claims are dubious, the high salt content might have had some antiseptic properties.

The Fall of a Fish Sauce Empire

For centuries, the garum trade flourished. So why don’t we douse our food in it today? The decline of garum is intrinsically linked to the decline of the Western Roman Empire itself.

The complex, long-distance trade routes that brought Spanish garum to Rome and Roman garrisons in Britain depended on the security provided by the Roman navy. As the empire fractured in the 4th and 5th centuries CE, piracy became rampant, making maritime trade perilous and expensive. Furthermore, heavy taxes on salt, a crucial ingredient, made large-scale production increasingly uneconomical.

The garum empire didn’t vanish overnight. Instead, it decentralized. Production became local and small-scale. Over time, the tradition evolved. One of its direct descendants survives today in the small Italian fishing village of Cetara, where a sauce called Colatura di Alici is still made by fermenting anchovies—a faint, delicious echo of the flavour that once conquered the world.

Garum is more than a historical curiosity. It was the liquid engine of the Roman economy and the defining taste of its culture. It connected soldiers, senators, and slaves in a shared culinary experience, proving that sometimes, the most powerful empires can be built on something as simple, and as pungent, as fish.