Imagine a government where the highest positions weren’t held by hereditary nobles or wealthy merchants, but by poets and philosophers. For over 1,300 years, this was the reality in imperial China. The empire was run by a unique class of men known as the shi dafu (士大夫), or scholar-officials. They were the intellectual and political elite, individuals who earned their power not through birthright, but through the mastery of literature, philosophy, and a grueling, life-defining examination system. Their story is one of immense ambition, profound cultural creation, and the enduring tension between high-minded ideals and the messy reality of power.

The Ink-Stained Path to Power: The Imperial Examinations

The key that unlocked the doors of power was the imperial examination system, formally established during the Sui dynasty (581–618) and solidified in the Tang (618–907). In theory, it was a perfect meritocracy: any man, regardless of his family’s wealth or status (though merchants and artisans were often excluded), could become a high-ranking official if he was smart enough and studied hard enough. The reality was more complex, as only families with some resources could afford the years of dedicated education required to succeed.

The journey was a brutal intellectual gauntlet. It consisted of a series of examinations at different levels:

- County/Prefectural Exams: Held locally every few years, passing these granted a candidate the entry-level degree of shengyuan (生員), or “government student.”

- Provincial Exams: Held every three years, these were far more intense. Candidates were locked into small, spartan cells for three days and two nights to compose essays and poems on complex philosophical and historical topics. Success earned them the title of juren (舉人), or “recommended man”, andqualified them for minor official posts.

- Metropolitan and Palace Exams: The final hurdle, held in the capital. The top candidates from the provincial exams competed one last time, with the very final palace exam often held in the presence of the emperor himself. Those who passed became jinshi (進士), or “advanced scholars”—the most coveted degree and a near-guarantee of a prestigious government career.

What were they tested on? Not law, economics, or military strategy. The curriculum was centered entirely on the Confucian classics, particularly the “Four Books and Five Classics.” Candidates had to memorize these texts—hundreds of thousands of characters—and be able to expound upon them in the highly structured and notoriously difficult “eight-legged essay” format. The goal was to produce officials who shared a common moral and philosophical framework, ensuring that the state was governed by men steeped in Confucian principles of order, duty, and benevolence.

The Life of a Scholar-Bureaucrat: Ideals vs. Reality

Once a scholar passed the exams and received a post, his life became a balancing act. As a Confucian scholar, he was expected to be a paragon of virtue, a junzi (gentleman) who pursued righteousness (yi) and benevolence (ren). He was a moral guide for the people and a loyal but honest critic of the throne, obligated to speak out against injustice, even at great personal risk.

As an official, however, he was a practical administrator. A county magistrate—the lowest level of official posting—was responsible for everything in his jurisdiction: tax collection, judicial hearings, infrastructure maintenance, public works, and social order. He was both mayor and judge, police chief and public works director. Moving up the ladder, scholar-officials became governors, ministers at the imperial court, and grand secretaries who advised the emperor directly.

This duality created immense pressure. The Confucian ideal of a pure, scholarly life often clashed with the rampant corruption, bureaucratic infighting, and moral compromises of a political career. The scholar-official was a man torn between the ivory tower of philosophy and the muddy trenches of governance.

Masters of the Brush and the Word

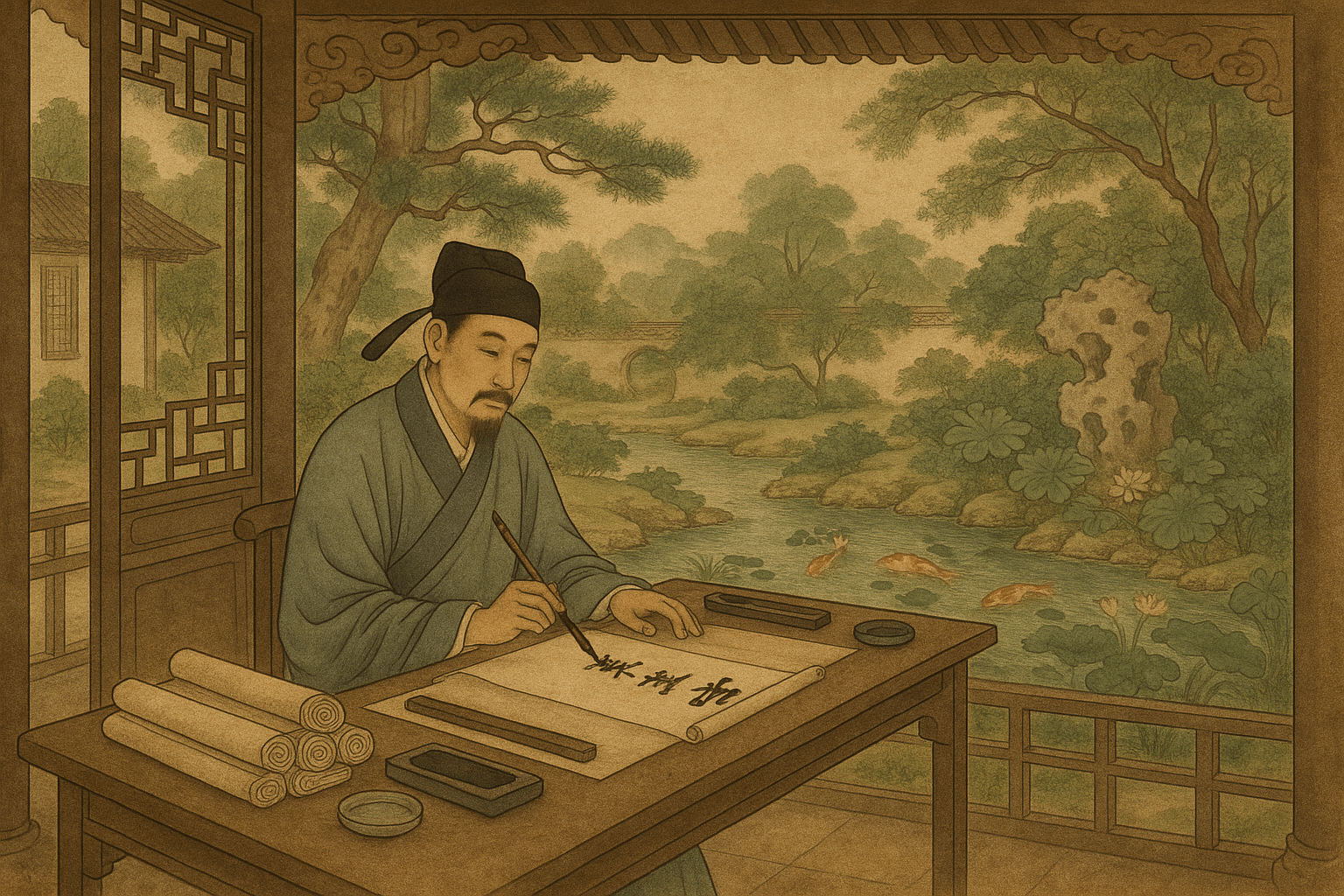

This tension found its most eloquent expression in art. The scholar-official was not just a politician; his demanding education made him a master of the “Four Arts”: the qin (zither), qi (the board game Go), shu (calligraphy), and hua (painting). Art was not a mere hobby; it was an essential part of their identity. Poetry, in particular, was the language of the elite.

Perhaps no one embodies this ideal better than Su Shi (1037–1101), also known as Su Dongpo, a giant of the Song dynasty. A brilliant poet, calligrapher, and statesman, Su Shi’s career was a dramatic cycle of high office and devastating political exile. Sent to a remote outpost for opposing the powerful reformer Wang Anshi, he didn’t just wallow in despair. Instead, he cultivated a farm, practiced Chan Buddhism, and produced some of China’s most celebrated works of art and literature. In his famous poem, “First Rhapsody on the Red Cliffs”, he reflects on history, nature, and the fleeting nature of human ambition:

“Between heaven and earth, we are no more than a grain of millet on the vast ocean. I mourn the passing of a single moment, and envy the eternal flow of the Great River.”

For men like Su Shi, art was the space where they could process their political frustrations, express their philosophical insights, and strive for a sense of inner peace that the political world so often denied them.

The Perils of Politics: Factionalism and Exile

The corridors of power were rarely tranquil. Because scholar-officials shared the same classical education, disagreements often arose from different interpretations of Confucian doctrine and how it should be applied to governing. This led to intense factionalism at court. These were not modern political parties, but loose alliances of officials who shared a philosophical outlook or a common mentor.

The most famous example was the bitter struggle in the 11th-century Song dynasty between the reformers, led by Chancellor Wang Anshi, and the conservatives, led by historian Sima Guang and poet Su Shi. Wang Anshi pushed for radical “New Policies” to reorganize state finances and strengthen the military. The conservatives argued that his policies were a betrayal of traditional Confucian values and would destabilize society. The debate was fierce, intellectual, and had profound real-world consequences. When one faction gained the emperor’s ear, its opponents were demoted, dismissed, or exiled to the farthest corners of the empire.

The End of an Era: Legacy and Decline

For centuries, the scholar-official system provided China with a stable, sophisticated, and remarkably effective bureaucracy. It fostered a deep reverence for education and created a ruling class that produced an unparalleled legacy of art, literature, and philosophy. The very idea of a meritocratic civil service was centuries ahead of its time.

However, the system was also a double-edged sword. Its focus on literary and philosophical knowledge meant that practical skills in science, engineering, and economics were neglected. The rigid format of the exams could stifle creativity and encourage conformity. By the 19th century, in the face of rapid technological advancement and aggressive Western imperialism, the system seemed woefully inadequate.

Confronted by military defeats and internal rebellion, reformers within the Qing court argued that the Confucian curriculum was holding China back. Finally, in 1905, the imperial examination system that had defined China’s elite for 1,300 years was abolished. The scholar-official faded into history, and just a few years later, the entire imperial system collapsed.

Though the scholar-officials are gone, their legacy endures. They built a system of governance whose influence can still be seen in modern civil service exams around the world. They left behind a cultural treasure trove that continues to define Chinese aesthetics and thought. More than anything, they represent a grand and fascinating experiment in history: the attempt to build a state ruled not by brute force or inherited wealth, but by the power of the written word.