A Dream of Unification: Early Beginnings

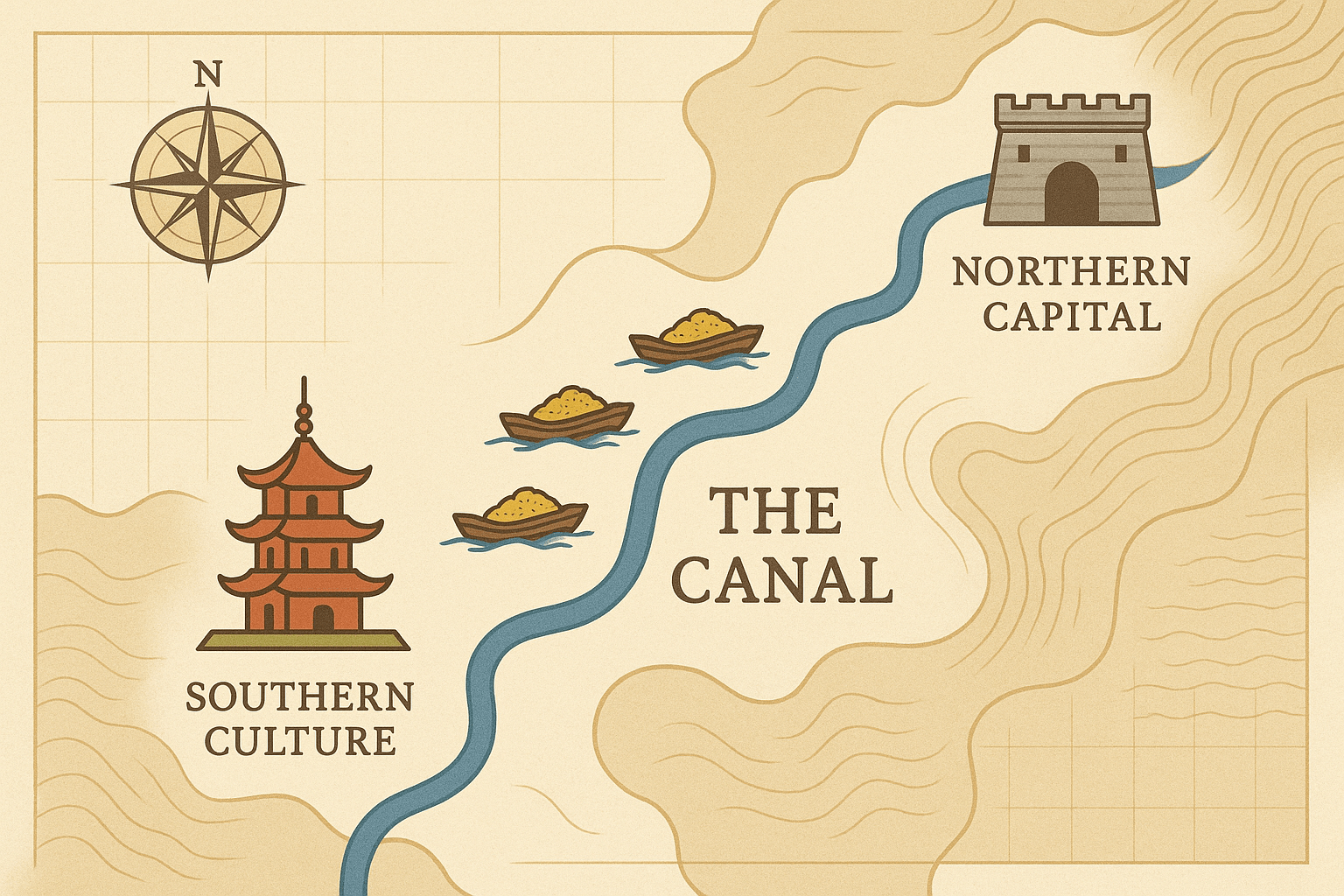

To understand why the canal was so crucial, one must first understand China’s geography. Its two great rivers, the Yellow River in the north and the Yangtze River in the south, flow from west to east. This created a formidable natural barrier, dividing the country into a political and military north and a fertile, agricultural south. For any ruler hoping to govern a unified China, this divide was a fundamental strategic problem.

The first attempts to solve it were modest. As early as the 5th century BC, a local ruler named Fuchai of Wu ordered the construction of a canal to link the Yangtze with the Huai River for military advantage. Throughout the subsequent centuries, various states and dynasties built and connected smaller canals for local transport and irrigation. These were important regional projects, but they were mere capillaries compared to the great artery to come.

The Sui Dynasty’s Ambitious (and Deadly) Undertaking

The true birth of the Grand Canal as a unified, nation-spanning system was the vision—and obsession—of one man: Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty (581-618 AD). After reunifying China after centuries of division, Emperor Yang launched one of the most ambitious engineering projects in human history.

His motivations were threefold:

- Economic Control: The Yangtze River Delta in the south was China’s breadbasket, producing a massive surplus of rice and grain. The north, however, was home to the political capital and enormous armies guarding the frontier. The canal was designed to be a superhighway for the “grain tribute”—a tax paid in grain—that would feed the court, bureaucracy, and soldiers in the north.

- Military Logistics: Emperor Yang had grand military ambitions, particularly against the Goguryeo kingdom on the Korean peninsula. The canal allowed him to move vast armies and their supplies from the heartland to the northern frontier with unprecedented speed.

- Political Unification: By linking the political center in the north with the economic and cultural hub in the south, the canal was a tool of centralization. It allowed the emperor to project his power and integrate the two culturally distinct halves of his empire.

The construction, completed in a staggering six years, came at an almost unimaginable human cost. Millions of conscripted laborers, including women and the elderly, were forced to toil under brutal conditions. It is said that the bodies of those who perished from exhaustion and disease were simply used as fill in the canal’s embankments. This immense cruelty and the massive tax burden required to fund the project fomented widespread resentment, ultimately leading to rebellions that toppled the Sui Dynasty. Ironically, the very project designed to secure the empire led to its swift demise.

The Golden Artery of the Tang and Song

While the Sui fell, their creation endured. The succeeding Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties reaped the rewards of the Sui’s brutal labor, and the canal entered its golden age. Now fully operational and well-maintained, it became the undisputed economic backbone of the empire.

The grain tribute system became a finely tuned machine, with fleets of barges carrying millions of tons of rice northward each year. This reliable food supply stabilized the state and allowed for the growth of massive urban centers like the capital, Chang’an. But the canal was no longer just a government tool. It exploded as a commercial highway. Merchants used it to transport salt, tea, silk, porcelain, and countless other goods, sparking an economic boom. Cities along its route, such as the magnificent Yangzhou, became bustling, cosmopolitan hubs of commerce, art, and entertainment, celebrated by poets like Li Bai.

Just as importantly, the canal became a conduit for culture. Officials traveling to and from the capital, scholars heading to imperial examinations, and artists seeking patronage all journeyed along its waters. It facilitated a vibrant exchange of ideas, blending the refined, literary culture of the south with the martial, political traditions of the north, and helped forge a more cohesive Chinese identity.

A New Route for a New Capital: The Yuan Upgrade

The canal’s route was not static. When the Mongols conquered China and established the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), they moved the capital to Dadu (modern-day Beijing). This new northern capital was far off the canal’s original path. To solve this, Kublai Khan commissioned another monumental engineering feat: straightening the canal.

Under the masterful eye of the astronomer and engineer Guo Shoujing, workers dug a new, more direct route. This involved complex challenges, like building a 30-mile-long “summit” section across the Shandong highlands and devising a system of locks and feeder reservoirs to supply it with water—a testament to the sophistication of Chinese engineering. This new canal, much closer to the one we see today, ensured Beijing would be well-supplied for centuries to come.

Decline and Enduring Legacy

The Grand Canal remained the empire’s primary artery through the Ming (1368-1644) and into the Qing (1644-1912) dynasties. However, its dominance began to wane. The notoriously difficult-to-manage Yellow River repeatedly changed course, causing catastrophic floods that silted up and destroyed sections of the canal, requiring constant, expensive repairs.

By the 19th century, the advent of steam-powered sea transport provided a viable alternative for shipping grain north. Following devastating rebellions and the construction of modern railways in the early 20th century, the canal’s role as a national lifeline finally came to an end. Yet, it never disappeared. Today, parts of the canal are still used for local transport, and in 2014, it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It stands not as a relic, but as a living monument—a physical scar on the landscape that tells an epic story of imperial ambition, human suffering, and the incredible power of a single waterway to build, sustain, and unify a nation.