From General to Emperor: A Calculated Rise

Born Muhammad Toure, the future emperor was not of royal blood. He was a prominent general and the prime minister under Sunni Ali, the fearsome warrior-king who founded the Songhai Empire through relentless conquest. Sunni Ali was a military genius, but he ruled with an iron fist and had a tense, often hostile relationship with the Muslim scholars of major cities like Timbuktu.

When Sunni Ali died in 1492, his son, Sunni Baru, took the throne. Crucially, Baru refused to declare himself a Muslim, alienating the powerful urban Islamic elite. Seeing an opportunity and perhaps a necessity, Muhammad Toure challenged Baru’s legitimacy. In 1493, he defeated Baru’s forces at the Battle of Anfao. He didn’t just seize power; he legitimized his coup by framing it as a victory for Islam against a pagan pretender. He took the title “Askia”, a Songhai military rank, and a new dynasty was born.

The Pilgrimage that Redefined Power

Like Mansa Musa before him, Askia Muhammad undertook the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, from 1495 to 1497. But this was no mere repeat of Mali’s golden procession. Askia’s journey was a masterstroke of political and religious diplomacy. While he traveled with a large retinue and significant wealth, his primary goal was not to display riches but to absorb knowledge and secure legitimacy.

In Mecca, he cultivated relationships with scholars and rulers across the Islamic world. His most significant achievement was persuading the Sharif of Mecca, the nominal ruler of the holy city, to officially recognize him as the Caliph of the Sudan. This was a monumental title. It designated Askia as the spiritual and political leader of all Muslims in West Africa, placing his authority above all other regional kings. He returned to Songhai not just as an emperor, but as God’s chosen representative in the region, an unassailable position that became the bedrock of his authority.

Architect of an Empire: The Great Reforms

With his power consolidated, Askia Muhammad embarked on a series of radical reforms that transformed Songhai from a loosely-held collection of conquered territories into a highly efficient, centralized empire. He was the ultimate administrator.

A Professional Military

Under a new, unified command, Askia replaced the traditional system of raising feudal levies with a full-time, professional army. This standing army was loyal to the state, not to local chieftains, ensuring stability and rapid response. Critically, he also established a riverine navy of war canoes, commanded by the Hi-koi (Chief of the Navy), to patrol and control the vital Niger River—the empire’s commercial and transportational artery.

A Centralized Bureaucracy

Perhaps Askia’s most brilliant innovation was his restructuring of the government. He divided the vast empire into provinces, each overseen by a governor (fari or koi) he personally appointed. This broke the power of old, conquered royal families.

He then created a sophisticated imperial council with cabinet-like positions to manage the state’s affairs. These included:

- The Fanfa, a chief of finance who managed the treasury.

- The Korey-farma, a chief in charge of relations with white foreigners and traders from North Africa.

- The Hor-farma, a chief overseeing the numerous fishermen of the Niger.

- The Katal-farma, a chief of the army’s divisions.

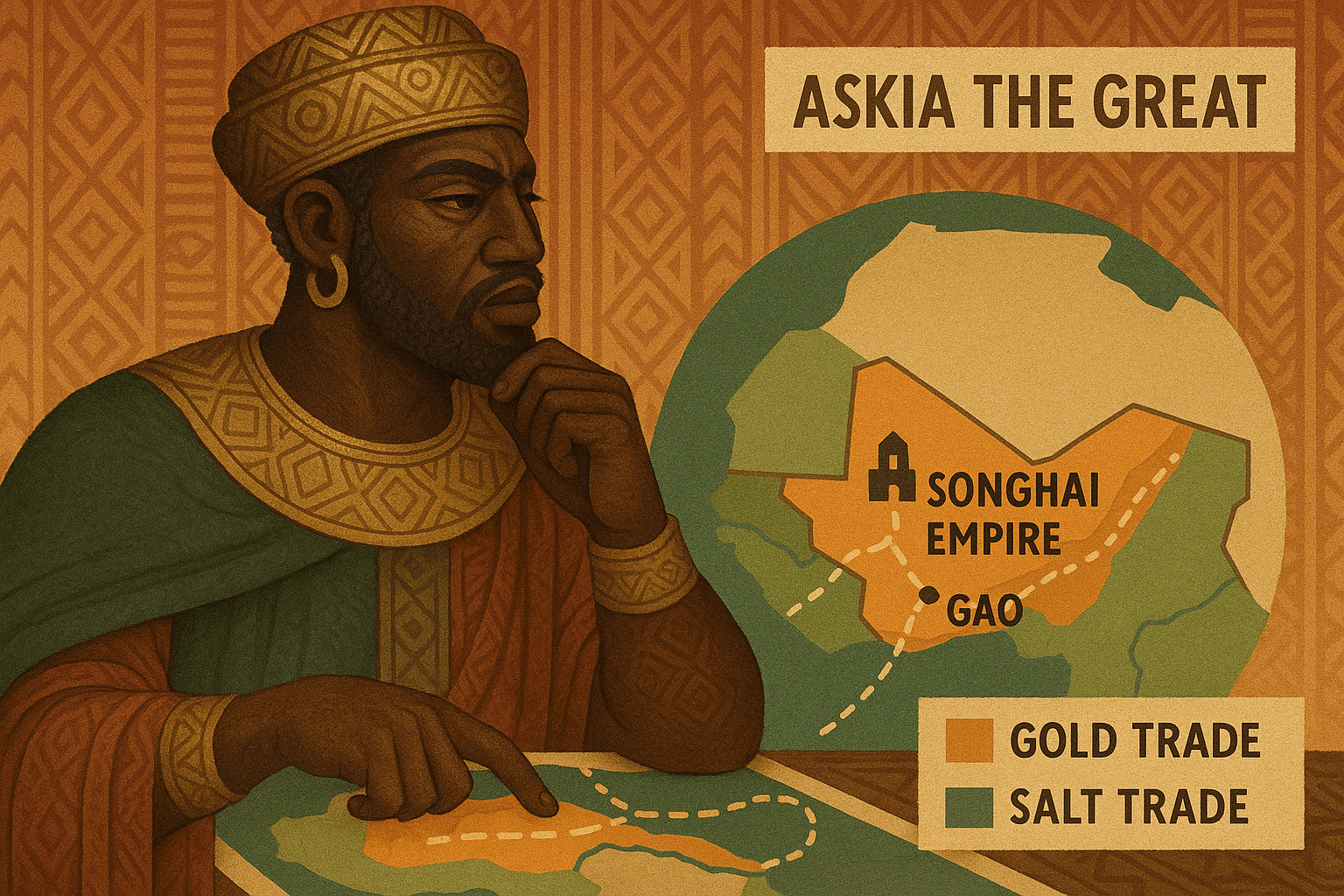

This intricate system allowed for efficient tax collection, resource management, and governance over a multi-ethnic, sprawling territory that stretched over 1.4 million square kilometers at its peak.

Economic Order and Fair Trade

Understanding that stability required economic prosperity, Askia standardized the tools of commerce. He introduced a system of uniformed weights and measures across the empire, replacing the chaotic local systems. He also appointed trade inspectors to the major markets in Timbuktu, Djenné, and Gao. These reforms fostered trust, eliminated fraud, and made trans-Saharan trade more predictable and profitable. The state, in turn, benefited from a more regular and easily managed system of taxes and tariffs on goods like salt, gold, and kola nuts.

A Golden Age of Learning

Askia was a devout Muslim and a great patron of education. He replaced traditional law with Islamic Sharia law throughout the empire, administered by a network of judges (qadis) he appointed. He invited scholars from Egypt and Morocco to settle in Timbuktu and Gao, turning them into world-renowned centers of learning.

Under his patronage, the Sankore University in Timbuktu flourished, attracting students from across the Muslim world. Libraries were built, and manuscripts were copied and studied extensively. Scholars like Ahmed Baba produced enormous bodies of work on law, history, and science, creating an intellectual golden age for West Africa.

An Unfortunate End and a Lasting Legacy

Askia the Great ruled for 35 years. His military campaigns expanded the empire to its largest extent, finally eclipsing the remnants of the Mali Empire and conquering the Hausa states to the east. However, his reign ended in tragedy. As he grew old and blind, his sons grew impatient. In 1528, he was deposed by his son, Musa. He died a decade later, in 1538.

Despite his deposition, Askia’s legacy was secure. He had transformed Songhai into a model of imperial administration. The systems he built—the professional army, the centralized bureaucracy, the standardized economy, and the patronage of scholarship—allowed the empire to thrive for decades after his rule. While Sunni Ali was the conqueror who laid the foundation, it was Askia the Great who served as the master architect, building a stable, prosperous, and intellectually vibrant structure upon it. His reign stands as a powerful testament that the true strength of an empire lies not just in its size or its wealth, but in its organization, its justice, and its vision.