Imagine a ruthless emperor, his hands stained with the blood of a hundred thousand souls, suddenly renouncing an entire lifetime of conquest. Imagine this ruler, at the zenith of his power, trading the sword for a philosophy of peace and compassion. This isn’t the plot of a fantasy novel; it’s the remarkable true story of Ashoka, the third emperor of the Mauryan Empire, who transformed his kingdom into an “Empire of Dharma.” His message, carved on stone for eternity, offers one of history’s most profound lessons in leadership and morality.

The Blood-Soaked Catalyst: The Kalinga War

To understand Ashoka’s transformation, we must first look at the event that broke him: the Kalinga War (c. 261 BCE). Early in his reign, Ashoka was every bit the conventional emperor—ambitious, expansionist, and ruthless. The kingdom of Kalinga (modern-day Odisha) was a prosperous coastal state that stood as a final bastion of independence against Mauryan domination.

Ashoka’s conquest was brutally effective. His own inscriptions, particularly Major Rock Edict XIII, provide a chillingly personal account of the aftermath. He states that 100,000 people were killed in the fighting, 150,000 were deported, and many more perished from famine and disease. Walking through the battlefield, witnessing the catastrophic loss of life, Ashoka was struck by a “profound sorrow and regret.” The cries of the bereaved and the sight of the dead shook him to his core. This was not a victor’s glory; it was a human tragedy of his own making.

From Conquest to Dharma: A Radical Shift

The Kalinga War became the pivot upon which Ashoka’s entire worldview turned. He converted to Buddhism, but his subsequent actions went far beyond personal faith. It was a complete overhaul of state policy. Ashoka replaced the age-old doctrine of military conquest (*digvijaya*) with a radical new idea: Dharma-vijaya, or “conquest by righteousness.”

But what was this “Dharma”? While influenced by Buddhist teachings, Ashoka’s Dharma was a universal ethical code, designed to be applicable to everyone in his diverse empire, regardless of their religion or social status. It was a moral framework based on a few key principles:

- Ahimsa: Non-violence and non-injury to all living beings.

- Compassion: Kindness towards servants, respect for elders, and generosity to all.

- Tolerance: Amity and respect between different religious sects.

- Truthfulness: Upholding honesty in word and deed.

- Welfare: The duty of the ruler to care for his subjects like a father.

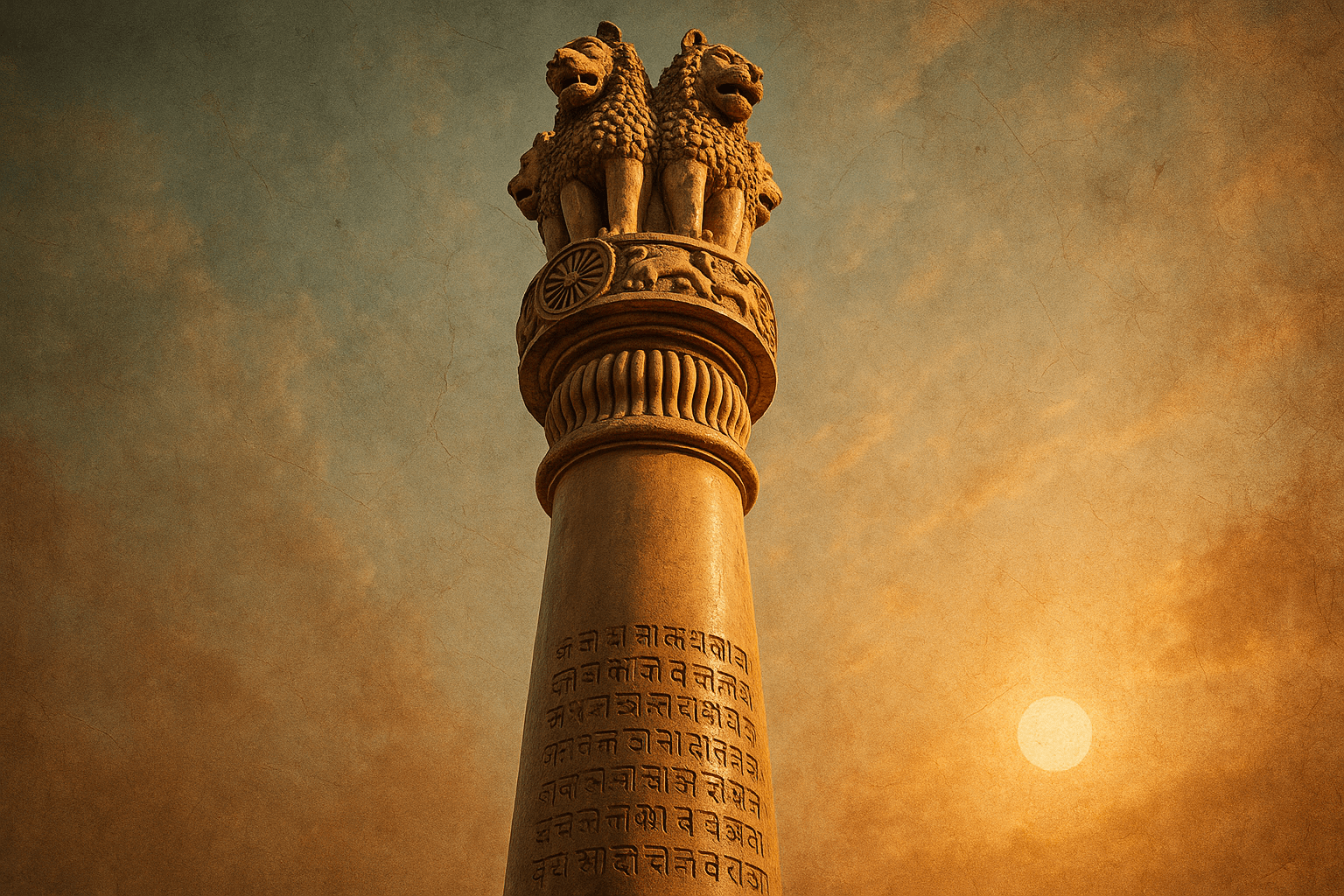

A Message Carved in Stone: The Edicts of Ashoka

Instead of royal decrees hidden in archives, Ashoka broadcasted his new philosophy across his vast domain. He had his policies and moral exhortations inscribed on massive rock formations and magnificent, polished sandstone pillars. These Edicts of Ashoka, found scattered across modern-day India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Nepal, were the world’s first large-scale public messaging campaign.

Written primarily in Prakrit (a common vernacular) using the Brahmi script, and in some frontier regions in Greek and Aramaic, they were meant to be read aloud and understood by the common person. They stand as a permanent record of his intentions and a blueprint for his ideal state.

The Core Teachings

The edicts reveal a ruler grappling with how to apply his newfound morality to the practical business of governing an empire.

Social Welfare as State Policy

Ashoka’s Dharma wasn’t just an abstract ideal; it was a blueprint for a welfare state. He understood that morality was difficult on an empty stomach. In his edicts, he proudly recounts his public works projects:

“On the roads I have had banyan trees planted, which will give shade to beasts and men, and I have had mango groves planted. And at intervals of eight kilometers, I have had wells dug, and rest houses built. And I have had numerous watering places made for the use of beasts and men.” – Pillar Edict VII

He also established medical facilities for both humans and animals, and sent officials, known as Dharma Mahamatras, to promote welfare and ensure justice throughout the empire.

A Plea for Non-Violence and Tolerance

Having witnessed the horrors of war, Ashoka became a fervent advocate for *ahimsa*. He drastically reduced the slaughter of animals in the royal kitchens and banned animal sacrifices that were central to many religious rituals of the time. While he did not enforce vegetarianism on his subjects, he consistently pleaded for restraint and compassion towards all living creatures.

Perhaps most strikingly, Ashoka championed religious tolerance in an age of sectarianism. Though a devout Buddhist, he never sought to impose his faith. Major Rock Edict XII is a powerful testament to this:

“Whoever praises his own sect or blames other sects—all out of devotion to his own sect, with the view of glorifying his own sect—he in fact injures his own sect more gravely.”

He urged his subjects not only to tolerate but to learn from and respect the beliefs of others, a message that remains profoundly relevant today.

A Father to His People

Ashoka redefined the relationship between ruler and subject. He abandoned the traditional image of the aloof, divine king and instead adopted a paternalistic role. One of the most famous lines from the Kalinga Edicts declares, “All men are my children.” Like a father, he felt a personal responsibility for the material and spiritual well-being of his people, promising them justice, security, and care.

The Legacy of an Empire of Dharma

Did Ashoka’s grand experiment succeed? The answer is complex. In the short term, the Mauryan Empire began to crumble within fifty years of his death in 232 BCE. Some historians argue his policy of non-violence may have weakened the empire’s military strength, leaving it vulnerable to invasion.

Yet, Ashoka’s true legacy was not the endurance of his dynasty, but the power of his ideas. His edicts, lost to time and written in a forgotten script, were silent for nearly two millennia. It wasn’t until 1837 that a British scholar and antiquarian, James Prinsep, finally deciphered the Brahmi script and reintroduced the great emperor to the world.

Today, Ashoka’s legacy is embedded in the identity of modern India. The national emblem of India is an adaptation of the Lion Capital from an Ashokan pillar at Sarnath. The wheel in the center of the Indian flag is the Ashoka Chakra, representing the eternal wheel of Dharma. Ashoka’s attempt to build a state on the foundations of compassion, non-violence, and tolerance remains one of history’s most profound and inspiring experiments in governance, a timeless message in stone for all humanity.