When we picture Ancient Rome, the colossal arches of the aqueducts inevitably come to mind. These monumental structures, snaking for miles across the countryside, are the ultimate symbols of Roman engineering prowess. They carried millions of gallons of fresh water into a bustling metropolis of nearly a million people. But the story doesn’t end where the water enters the city. In fact, that’s where the real challenge began.

Who ensured this life-giving water reached the public fountains, the grand imperial baths, and the villas of the wealthy? Who maintained the complex network of pipes and channels? And, crucially, who fought the constant battle against corruption and theft? Step beyond the aqueducts and meet the unsung heroes of Rome’s water supply: the Curatores Aquarum, the “Water Commissioners” of Rome—or, as we might call them, the city’s first Water Police.

A City Built on Water

To understand the importance of the Curatores Aquarum, we must first grasp the sheer scale of Rome’s dependence on water. By the height of the Empire, eleven major aqueducts supplied the city. This wasn’t just for drinking. Water was the engine of Roman urban life. It fed the sprawling public bath complexes (thermae), which were centers of social life, business, and hygiene. It powered public latrines, ran in thousands of public fountains, and supplied workshops and businesses. The wealthiest Romans even paid for private connections to their homes, a status symbol of immense prestige.

Managing this system was a Herculean task. The aqueducts were not just fire-and-forget projects; they were living infrastructure that required constant monitoring and repair. Without a dedicated body to oversee them, Rome would have quickly descended into a state of thirst and filth.

The Rise of the Water Commissioners

In the early days of the Republic, responsibility for the water supply fell to various magistrates like the censors and aediles, but their oversight was often temporary and inconsistent. The system was revolutionized under Emperor Augustus. In his quest to professionalize the administration of Rome, he established a permanent board of commissioners in 11 BC, the cura aquarum.

This was no small-time municipal job. The three men chosen to be Curatores Aquarum were of the highest rank, typically ex-consuls and distinguished senators. Their appointment signaled the immense importance the emperor placed on the city’s water supply. The most famous of all these commissioners is Sextus Julius Frontinus, who served under Emperor Trajan around 97 AD. Luckily for history, Frontinus was a diligent administrator who wrote a comprehensive two-volume report on his work, De Aquis Urbis Romae (“On the Waters of the City of Rome”). His writings give us an unprecedented look into the world of the Roman water police.

The War on Water Theft

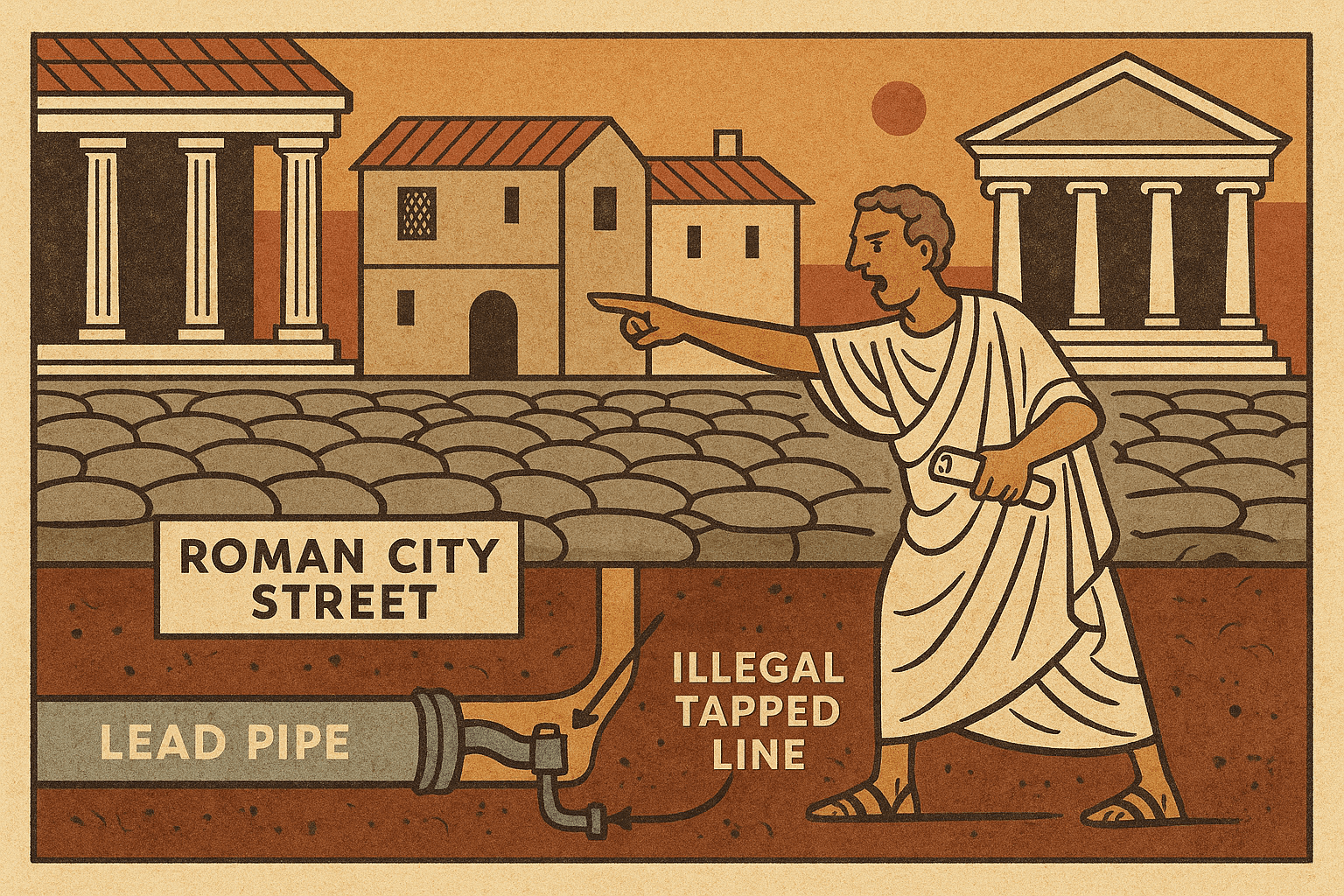

When Frontinus took office, he was shocked by what he found. The water system was riddled with fraud and illegal activity. He discovered that the amount of water being delivered to the city was far less than the amount entering the aqueducts. The difference was being siphoned off by countless illegal taps.

“A large number of landowners… tap the conduits for the use of their gardens”, Frontinus wrote, noting that this not only stole water but also created constant leaks and structural damage to the primary channels. This was a crime known as pungere (“puncturing”).

The methods of theft were varied and ingenious:

- Illegal Pipes: Wealthy villa owners or opportunistic farmers would secretly puncture the main aqueduct channel and install their own pipes to divert water to their property.

- Fraudulent Gauges: Every legal private connection was granted a specific nozzle, or calix, of a regulated size to control the volume of water. Frontinus found that many users had installed larger calices than they were authorized for, or had placed them in a way that increased the water pressure, allowing them to draw more than their share.

- “Leapfrogging”: Some crafty individuals with a legal grant would install additional pipes branching off from their primary line to supply their neighbors for a fee, essentially reselling state water.

The Curatores Aquarum and their staff, a specialized workforce known as the familia aquaria, were tasked with stamping out this corruption. This team of around 240 engineers, plumbers, surveyors, and guards patrolled the aqueduct lines, inspected junctions, and verified the legality of thousands of private connections. They were empowered by law, such as the Lex Quinctia of 9 BC, which imposed heavy fines for anyone who damaged, pierced, or otherwise interfered with the aqueducts. Frontinus’s work was essentially a city-wide audit, cross-referencing imperial grants with the physical pipes on the ground to reclaim stolen water for the public good.

More Than Just Cops: Engineers and Administrators

While chasing down water thieves was a major part of the job, the Curatores Aquarum were far more than just a police force. Their duties were a complex blend of engineering, administration, and civic planning.

Maintenance and Repair: The aqueducts required relentless upkeep. The channels constantly accumulated mineral deposits (calcium carbonate, or sinter) that had to be chipped away to maintain flow. Leaks needed plugging, and sections damaged by tree roots or small earthquakes required immediate repair. The Curatores managed the budget and manpower for these endless tasks.

Distribution and Quality Control: Not all aqueduct water was of the same quality. The pristine water from sources like the Aqua Marcia was reserved for drinking and cooking. Water from less-pure sources, like the Aqua Alsietina, was used primarily for industrial purposes or for filling the lake in Augustus’s mock naval stadium. The commissioners had to manage this complex distribution, directing the right water to the right places via distribution tanks called castella aquae.

Bureaucratic Oversight: Frontinus’s book is a testament to the immense record-keeping involved. The office of the Curatores Aquarum maintained detailed maps of the system, records of water volume (measured in a unit called a quinaria), and registers of every legal water grant issued by the emperor. This was sophisticated, data-driven management on an imperial scale.

The Unseen Legacy

The magnificent arches of the aqueducts are what survive, but they are only half the story. Their success hinged on the diligence and authority of the Curatores Aquarum. These elite officials and their teams were the guardians of Rome’s most precious resource. Through their relentless fight against corruption, meticulous record-keeping, and expert engineering management, they ensured that the baths remained full, the fountains ran freely, and a city of one million people did not go thirsty.

Their work is a powerful reminder that Roman greatness was built not only on stone and concrete, but on the sophisticated systems of administration and law that made their grandest achievements possible.