The Hellenistic Dawn of Automation

Our journey begins not in Silicon Valley, but in the bustling, cosmopolitan city of Alexandria in the 1st century AD. This was the intellectual heart of the Hellenistic world, and home to a brilliant mathematician and engineer named Hero (or Heron). Building on the work of predecessors like Ctesibius and Philo of Byzantium, Hero wasn’t just a theorist; he was a master of pneumatics, hydraulics, and mechanics. In his writings, he detailed plans for more than just steam engines—he designed what can only be described as automata.

Imagine walking up to a grand temple in ancient Alexandria. As the priest lights a fire on the altar outside, the massive temple doors swing open on their own, as if by divine will. Magic? No, it was Hero’s engineering. The heat from the fire would expand the air in a hidden chamber beneath the altar. This pressurized air would push water from one container into another, which, acting as a counterweight, would pull on a series of ropes and pulleys to open the doors. When the fire was extinguished, the process reversed, and the doors slowly closed. It was a spectacular piece of theatrical engineering, designed to inspire awe and reverence.

But Hero’s genius wasn’t limited to grand gestures. He also invented the world’s first known vending machine. A worshipper would insert a coin into a slot on a holy water dispenser. The weight of the coin would tip a small lever, opening a valve just long enough to dispense a set amount of water before the coin slid off and the valve closed. He even designed entire miniature theaters with automated figures that would move, dance, and act out entire myths, all powered by a complex system of falling weights and strings.

The Golden Age of Clockwork Wonders

As the Roman Empire waned, the flame of Hellenistic knowledge wasn’t extinguished. It was carefully preserved and brilliantly expanded upon in the Islamic world and the Byzantine Empire, leading to a renaissance of mechanical creation.

Ingenious Devices of the Islamic World

In the 9th century, the three Banu Musa brothers in Baghdad’s House of Wisdom penned the “Book of Ingenious Devices.” This remarkable text described over a hundred inventions, many of them automated. They designed trick fountains that would change their spray patterns, a self-filling and self-cleaning basin, and even a “mechanical waitress” that could serve tea.

However, the undisputed master of this era was Ismail al-Jazari, a 12th-century engineer who served the Artuqid court in what is now modern-day Turkey. His “Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices” is a stunningly illustrated manual of his creations. Al-Jazari’s machines were practical, artistic, and incredibly complex.

His most famous creation is the Elephant Clock. Standing over 20 feet tall, it was a magnificent multicultural spectacle. A mechanical rider on an Indian elephant would strike a cymbal, a Chinese dragon would descend to catch a ball dropped from the beak of a phoenix on an Egyptian-style phonoxt, and a scribe would mark the passing of the half-hour. The entire mechanism was powered by a hidden water-powered system of floats, pulleys, and triggers—a true masterpiece of medieval engineering.

Al-Jazari also created a musical robot band designed to entertain guests at royal parties. Four mechanical musicians—a harpist, a flutist, and two drummers—floated on a boat in a lake, playing music to a programmable rhythm set by pegs on a revolving cylinder. This programmable drum machine is one of the earliest examples of storing a “program” to be executed by a machine.

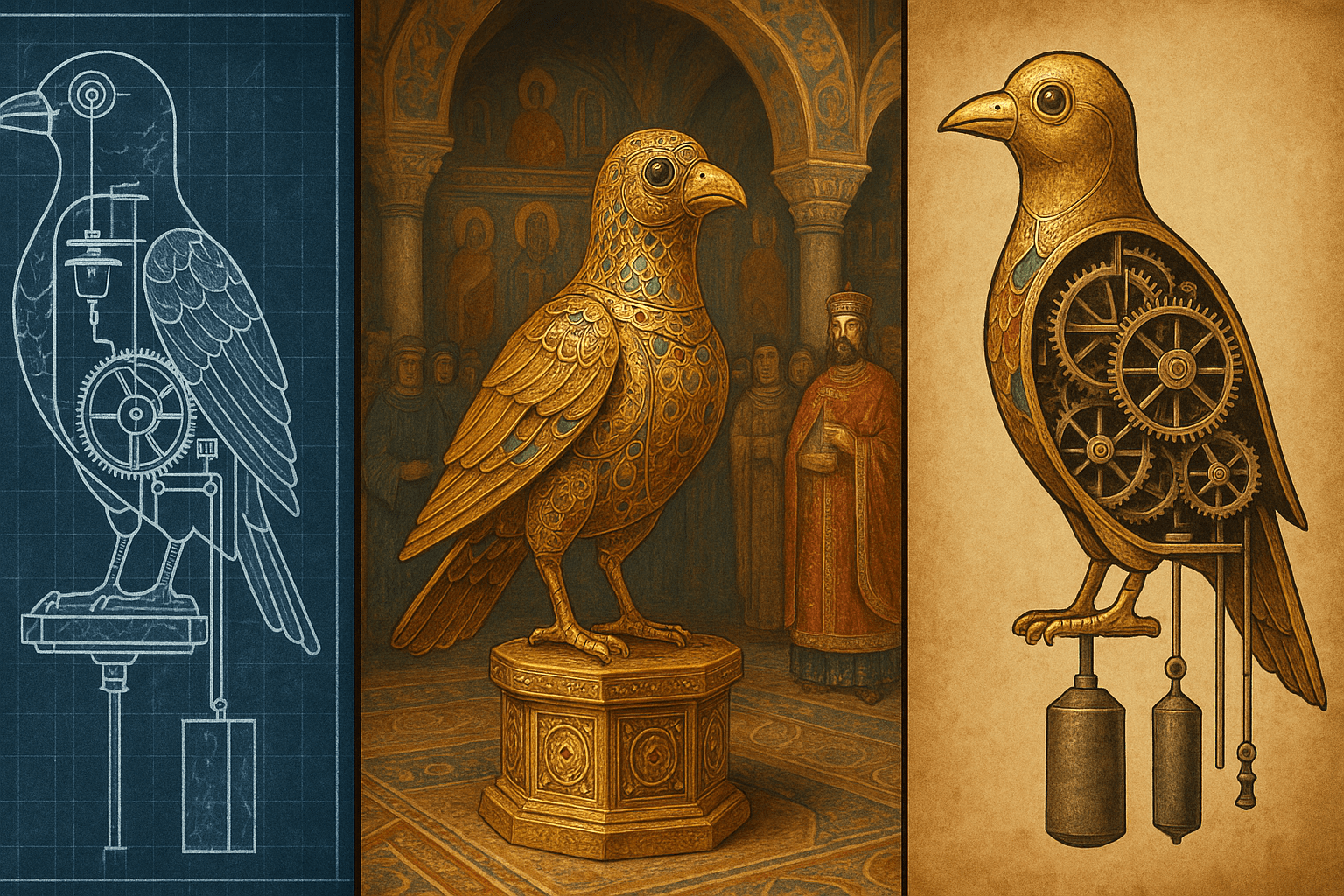

The Emperor’s Mechanical Menagerie

Meanwhile, in the opulent court of Constantinople, automata served a different purpose: diplomacy and power projection. The Byzantine emperors used mechanical wonders to dazzle and intimidate foreign visitors, creating an aura of almost divine authority.

Liutprand of Cremona, a 10th-century ambassador, described a visit to the Emperor’s throne room in the Magnaura palace. Before the throne stood a bronze tree, its branches filled with mechanical birds of different kinds, each singing the tune of its own species. The Emperor’s throne itself was flanked by golden lions that would beat the ground with their tails and let out a deafening roar with open mouths. Most astonishingly, as Liutprand prostrated himself, he looked up to find that the throne, with the Emperor still seated, had been hoisted to the ceiling.

Medieval Europe’s Awakening

For centuries, Western Europe lagged behind its eastern neighbors. But through cultural exchange in Spain, Sicily, and during the Crusades, this knowledge began to trickle back. By the High Middle Ages, European artisans were catching up.

The 13th-century sketchbook of Villard de Honnecourt contains designs for a perpetual motion machine and an automaton angel that would always point its finger toward the sun. But the most public displays of this newfound skill were the magnificent astronomical clocks built on the facades of cathedrals in cities like Strasbourg, Prague, and Bern.

These clocks did more than just tell time; they were mechanical calendars and planetariums. At the strike of the hour, they would burst into life. Figures of the Apostles would parade before Christ, a mechanical rooster would crow, and Death would ring a bell. These public spectacles combined religious storytelling with the pinnacle of mechanical art.

A Legacy of Artificial Life

From the temple doors of Alexandria to the roaring lions of Byzantium and the clockwork saints of Strasbourg, these ancient automata are more than historical curiosities. They represent a forgotten chapter in the history of robotics, driven by the same impulses that drive us today: the desire to entertain, the quest for knowledge, the projection of power, and the age-old human dream of creating artificial life.

These clockwork creations reveal that the line from the water-powered Elephant Clock to the AI-powered chatbot is longer and more continuous than we often imagine. The tools have changed—from hydraulics and gears to silicon and code—but the fundamental ambition to make the inanimate move, think, and interact has been with us for millennia.