A City Reborn and Ready for the Spotlight

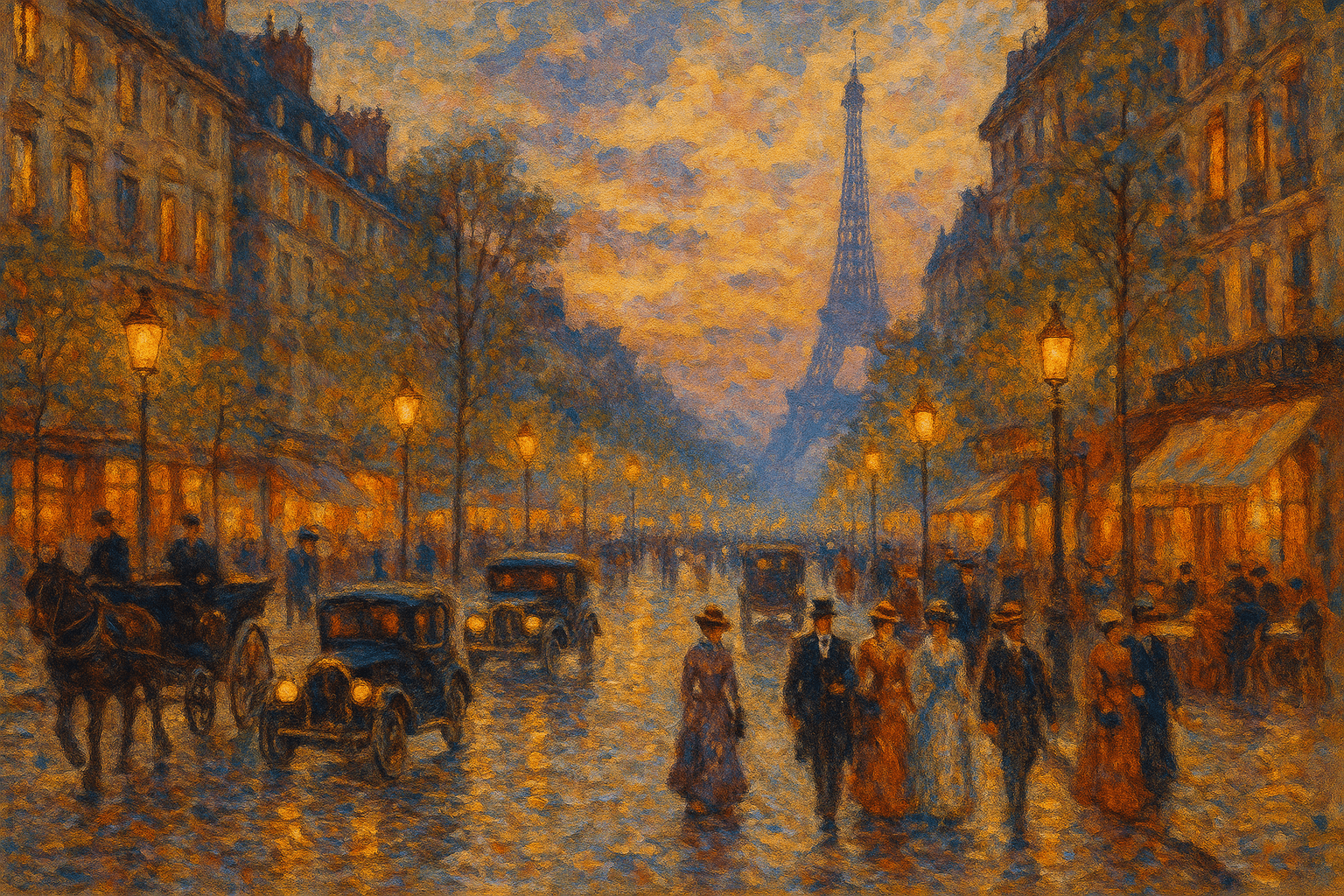

The stage for the Belle Époque was set by the ambitious urban renewal projects of Baron Haussmann under Napoleon III. Though largely completed before 1871, his work transformed Paris from a city of medieval alleys into a modern metropolis of wide, tree-lined boulevards, grand squares, and magnificent buildings. This new layout wasn’t just an aesthetic triumph; it fostered a new kind of public life. The culture of the flâneur—the leisurely stroller and observer of urban life—was born on these avenues. Parisians and visitors alike flocked to the new department stores like Le Bon Marché, sipped absinthe in bustling sidewalk cafés, and promenaded through the manicured parks. This physically transformed city became the perfect canvas for an unprecedented explosion of creativity and ideas.

The World Comes to Paris: The Expositions Universelles

Nothing demonstrated Paris’s global supremacy more than the series of spectacular World’s Fairs, or Expositions Universelles, it hosted. These were not mere trade shows; they were grand pronouncements of cultural, scientific, and industrial might that drew millions from every corner of the globe.

The Exposition Universelle of 1889, held to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, gave the world its most iconic symbol. Conceived as a temporary entrance arch to the fair, Gustave Eiffel’s iron tower soared 300 meters into the sky. Initially derided by the city’s artistic elite as a monstrous “iron asparagus”, the Eiffel Tower quickly became the definitive emblem of Parisian modernity and engineering genius.

Just over a decade later, the Exposition of 1900 was perhaps the zenith of the entire era. Attracting nearly 50 million visitors, it was a breathtaking spectacle celebrating the achievements of the 19th century while offering a tantalizing glimpse into the 20th. Attendees marveled at talking films, rode the first public escalator, and saw the premiere of the diesel engine. The fair left a permanent mark on the city’s landscape with the construction of the opulent Grand Palais and Petit Palais, linked to the Left Bank by the ornate Pont Alexandre III bridge.

The Epicenter of an Artistic Revolution

While the engineers built upwards, the artists of Paris were busy tearing down the old aesthetic order. The city was the undeniable cradle of modern art, attracting ambitious creators with its promise of freedom and intellectual ferment.

Impressionism and its Heirs

Rejecting the rigid, historical subjects of the official Salon, a group of audacious painters took their easels outdoors to capture the fleeting effects of light and the candid moments of modern life. They were the Impressionists. Claude Monet captured the shifting light on Rouen Cathedral, Pierre-Auguste Renoir painted the joyful crowds at the Bal du moulin de la Galette, and Edgar Degas revealed the gritty reality behind the graceful ballet dancers. Paris and its environs were their muse, and they forever changed the way we see the world. Hot on their heels came the Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, who used Paris as a crucial base for their even more radical explorations of color and form.

The Flourishing of Art Nouveau

As the 1900 Exposition dawned, a new aesthetic swept the city: Art Nouveau. Inspired by the organic, flowing lines of nature, this “New Art” sought to break the distinction between fine art and decorative objects. It was a total design movement, seen everywhere from painting to furniture. Its most famous Parisian legacy is in the sinuous, plant-like iron entrances to the new Paris Métro, designed by Hector Guimard. Art Nouveau was the visual language of the Belle Époque—elegant, modern, and utterly Parisian.

A Magnet for Thinkers and Innovators

Paris’s magnetism extended far beyond the arts. It was a global center for science and intellectual thought, where the very foundations of modern life were being laid.

- Scientific Breakthroughs: It was in her Parisian laboratory that Marie Curie, along with her husband Pierre, conducted groundbreaking research into radioactivity, making her the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in 1903 (she would win a second in 1911). The legacy of Louis Pasteur, whose institute was a hub of biological research, continued to shape modern medicine.

- Literary Giants: The literary scene was just as vibrant. Émile Zola’s novels explored the social realities of the city with unflinching naturalism, and his explosive open letter, J’Accuse…!, concerning the Dreyfus Affair, rocked the foundations of the Third Republic. In his cork-lined room, Marcel Proust began his monumental novel In Search of Lost Time, a deep dive into memory and the high society of the Belle Époque.

The Incandescent Glow of Joie de Vivre

Above all, the Belle Époque in Paris was defined by a pervasive sense of optimism and a lust for life—a joie de vivre. After the hardship of war, a generation embraced peace and prosperity with gusto. Entertainment was everywhere. The iconic Moulin Rouge in Montmartre, with its scandalous can-can dancers, represented a new, titillating form of mass entertainment. At the opulent Opéra Garnier and the dazzling Folies Bergère, spectacle became an art form.

This was an era of firsts: the first Michelin guide, the first Tour de France, and the first permanent cinema. Life was lived in public, in the cafés, concert halls, and on the boulevards. For a shining moment, Paris was a city that believed in progress, beauty, and pleasure above all else.

This “Beautiful Era”, however, was a finite and fragile paradise. Its light, so brilliant and dazzling, was burning on a short fuse. In the summer of 1914, the cannons of August silenced the music, and the world plunged into the darkness of the Great War. The dream of the Belle Époque was over, but its legacy endures in the art, architecture, and enduring spirit of Paris—the city that was, for a time, the capital of the world.