Before Apple, Amazon, or Google, before titans of industry like Rockefeller and Carnegie, there was a corporation so powerful it could wage war, mint its own money, and establish colonies. This was not a dystopian fantasy but a historical reality. Meet the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), or the Dutch East India Company—the world’s first multinational corporation, the first company to ever issue stock, and arguably the most powerful and ruthless megacorporation in history.

A Corporation Born of Ambition

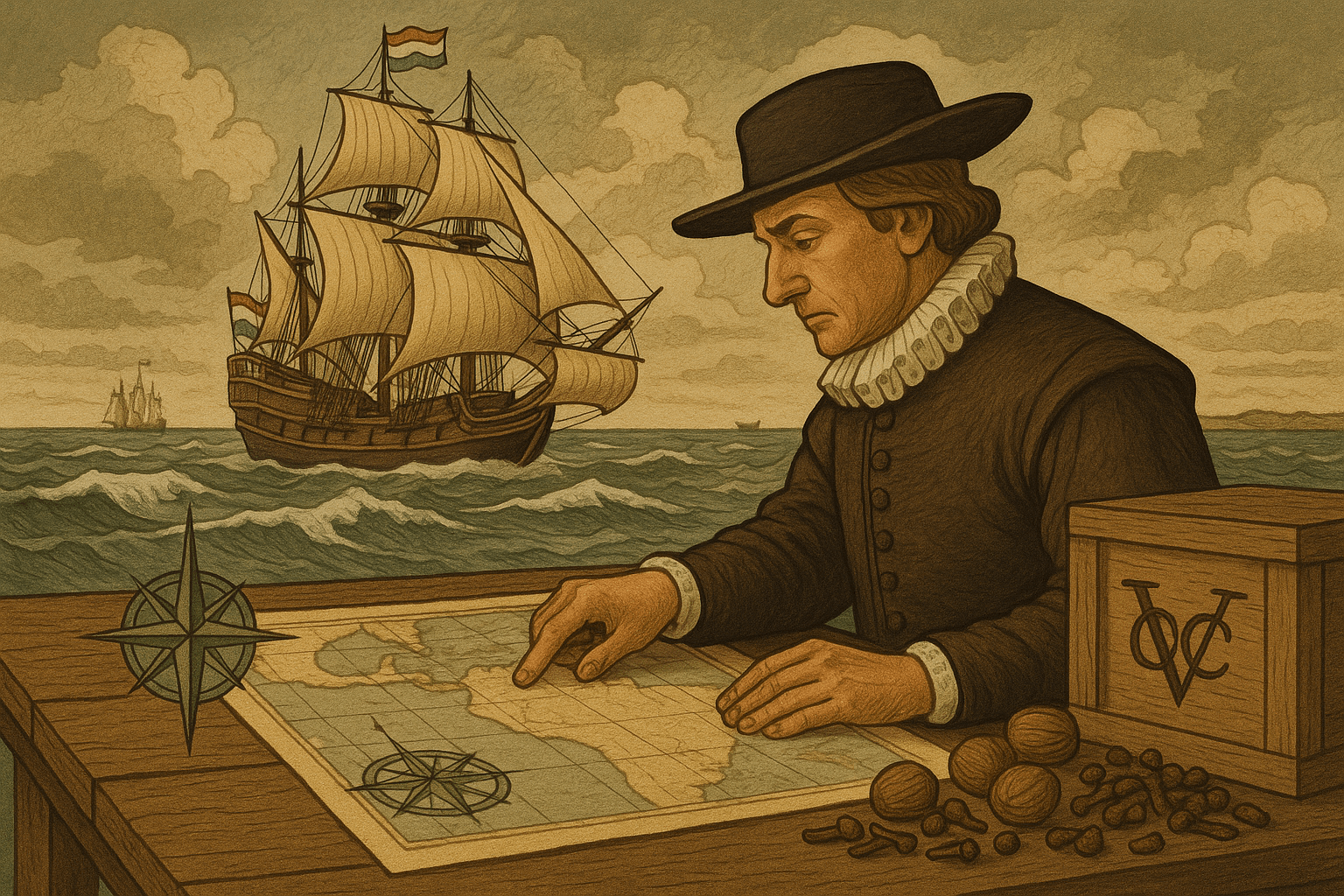

The year is 1602. The Dutch Republic, newly independent from Spanish rule, is buzzing with commercial energy. The most lucrative trade on the planet is in spices—nutmeg, mace, cloves, and pepper—which are worth more than their weight in gold. For decades, the Portuguese had dominated this trade, but their grip was weakening. Ambitious Dutch merchants launched their own perilous voyages to the East Indies (modern-day Indonesia), but their competition against each other was counterproductive, driving up purchase prices in Asia and lowering selling prices in Europe.

The Dutch government, the States-General, recognized the need for a unified front. In an unprecedented move, it forced these competing ventures to merge. The result was the VOC, a hybrid entity that was part corporation, part state. It was granted a 21-year monopoly on all Dutch trade east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Strait of Magellan. But its charter went much, much further. The VOC was given powers that today we associate only with sovereign nations:

- The right to wage war and negotiate treaties.

- The power to imprison and execute convicts.

- The authority to mint its own currency.

- The ability to establish colonies and build forts.

This wasn’t just a license to trade; it was a mandate to build an empire.

The Birth of the Stock Market

To fund this colossal undertaking, the VOC pioneered a revolutionary financial tool: public stock. For the first time, a company offered shares not just to a small circle of wealthy elites, but to the general public. Anyone—from powerful politicians to humble housemaids—could buy a piece of the company and a share in its future profits. This allowed the VOC to raise an enormous amount of capital, far more than any single monarch could have.

This innovation led directly to the creation of the world’s first-ever stock exchange in Amsterdam. Here, shares of the VOC were bought and sold, their value rising and falling based on news from distant seas, rumors of successful voyages, or the threat of war. Modern finance was born, all in service of acquiring spices from the other side of the world.

Monopoly Through Blood and Fire

The VOC’s core business was the spice monopoly, and it pursued this goal with terrifying brutality. The company quickly realized that to control the price of spices, it had to control the source. The primary target was the tiny Banda Islands, the world’s only source of nutmeg and mace.

The Bandanese people, however, were not interested in an exclusive trade deal. They had long traded with merchants from across Asia and continued to sell their valuable spices to the English, the VOC’s main rivals. This defiance was met with unimaginable violence.

The Banda Massacre: A Corporate Atrocity

In 1621, the ruthless Governor-General of the VOC, Jan Pieterszoon Coen, arrived at the Banda Islands with a fleet of warships and an army of mercenaries. His goal was simple and chilling: to eliminate the local population and replace them with slave labor loyal only to the company. Over the course of a few months, his forces systematically slaughtered, starved, and enslaved the Bandanese. Of the estimated 15,000 inhabitants, fewer than 1,000 survived. The islands were then repopulated with enslaved people forced to cultivate nutmeg exclusively for the VOC.

This act of corporate-sponsored genocide was not an anomaly. It was the VOC’s business model. Across the archipelago, the company used its private army—which at its peak numbered tens of thousands of soldiers—and its massive navy of over 150 merchant ships and 40 warships to enforce its will. They violently ousted the Portuguese from key ports, fought off the English, and forced local rulers into crippling contracts. To keep the price of cloves artificially high, the VOC would conduct annual expeditions to destroy any clove trees growing outside of its designated plantations.

A Globe-Spanning Empire

At its zenith in the mid-17th century, the VOC was a global colossus with no equal. Its value, in today’s money, has been estimated in the trillions of dollars, dwarfing any company that exists now. Its network spanned the globe.

The heart of its Asian empire was Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) in Java. From there, it managed a web of trading posts from the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, to the shores of India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and even to a small, artificial island in Nagasaki harbor, Japan, where the VOC was the only European entity permitted to trade for over 200 years.

The VOC was more than just a spice trader. It was the central artery of global trade, moving Japanese silver and copper to India, Indian textiles to the Spice Islands, and Chinese porcelain and tea to Europe. It was a true world-shaper.

The Inevitable Decline

No empire lasts forever. By the 18th century, the VOC was a victim of its own success and excesses. A culture of deep-seated corruption rotted the company from within; officials enriched themselves at the company’s expense. The Dutch wryly joked that VOC now stood for Vergaan Onder Corruptie—”Perished by Corruption.”

Competition from a revitalized British East India Company, shifting consumer tastes in Europe, and the immense cost of maintaining its massive military and administrative bureaucracy drained its coffers. The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780-1784) was a final, devastating blow, crippling the VOC’s fleet. Laden with insurmountable debt, the once-mighty corporation was nationalized by the Dutch government in 1796 and officially dissolved on December 31, 1799, nearly two centuries after its creation.

The Dutch East India Company leaves behind a complex and bloody legacy. It was a pioneer of global capitalism, corporate governance, and the stock market. Yet its innovations were built on monopoly, violence, and exploitation. Its story serves as a powerful and chilling reminder of what can happen when corporate power goes unchecked, a historical lesson that echoes in our modern debates about the role and responsibility of multinational corporations today.