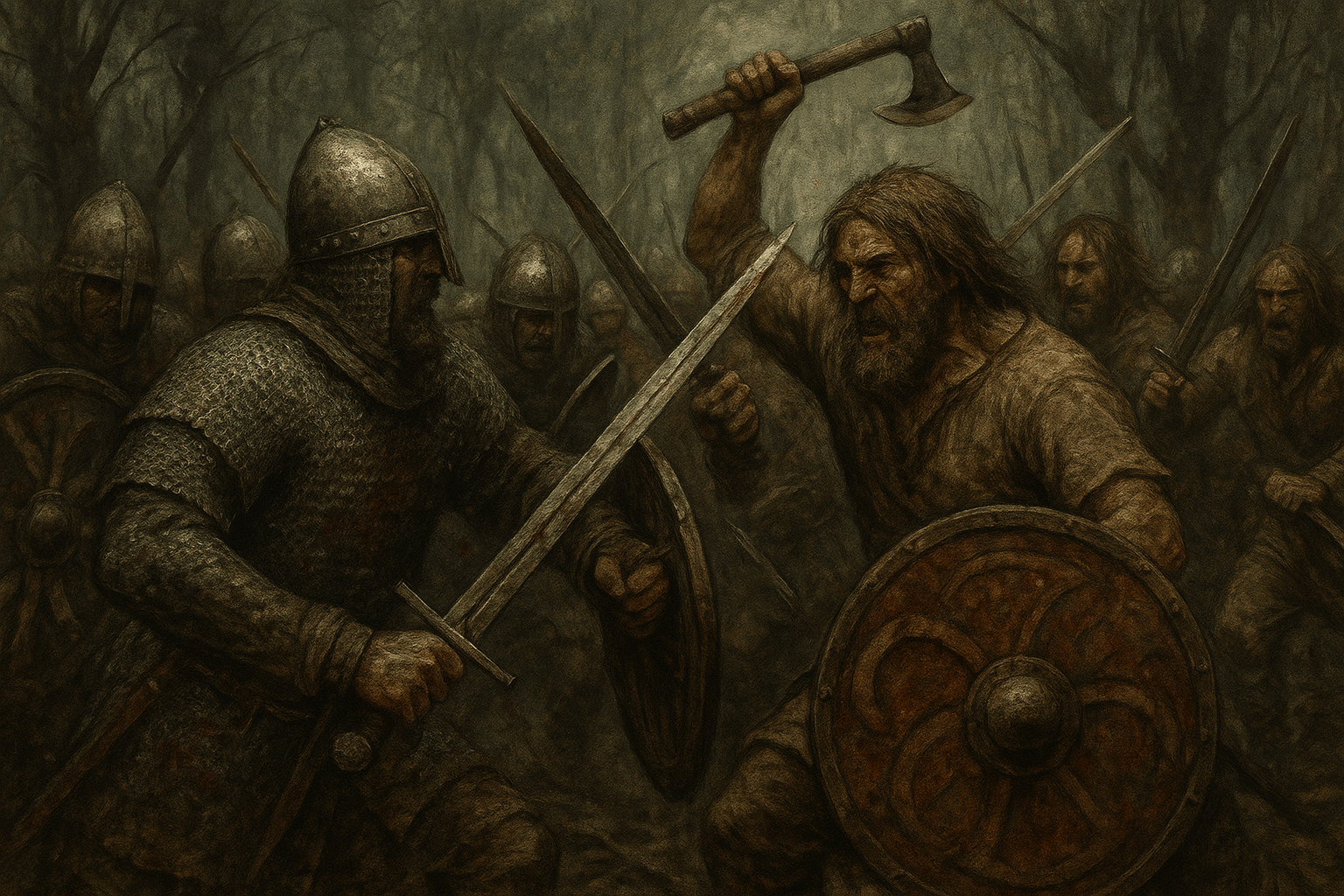

This campaign wasn’t fought in a distant, exotic land. It was waged in the forests and marshes of what is now northern Germany and Poland, by German, Danish, and Polish lords against their Slavic neighbors, the Wends.

Who Were the Wends?

The term “Wends” (from the German Wenden) was a collective name used by Germans for the various West Slavic tribes living between the Elbe and Oder rivers. This included major groups like the Obotrites and the Lutici. For centuries, they had followed their own polytheistic pagan traditions, worshipping gods like Radegast and Prove in sacred groves and temples.

Their relationship with their Christian neighbors was a complicated tapestry of trade, tribute, and intermittent warfare. German lords often exacted tribute from Wendish princes, while Wendish raiders, particularly those along the coast, were a constant menace to Danish shipping and coastal towns. This was not a clash of strangers, but a conflict between neighbors with a long, intertwined, and often violent history.

A Crusade on the Doorstep

The story begins in 1146, when Pope Eugene III issued the papal bull Quantum praedecessores, calling for a Second Crusade to retake Edessa in the Holy Land. The charismatic abbot Bernard of Clairvaux traveled through Europe, delivering fiery sermons that inspired thousands to take the cross.

However, when Bernard reached Saxony, he encountered a problem. The Saxon nobles were reluctant. Why, they argued, should they travel thousands of miles to fight an enemy in the desert when they had a “pagan” enemy right on their border? They saw an opportunity closer to home—a chance to deal with the Wends once and for all, with the full spiritual backing of the Church.

Seeing the logic—and the opportunity to keep the restless Saxon military might focused and sanctified—Bernard and the Pope agreed. In 1147, a new papal bull, the Divina dispensatione, officially sanctioned a crusade against the Wends. It offered the same spiritual rewards and indulgence (forgiveness of sins) to those who fought the Slavs in Europe as it did to those who journeyed to Jerusalem. The Northern Crusades had entered a new, official, and terrifying phase.

“Baptism or Annihilation”

What set the Wendish Crusade apart was its chillingly explicit goal. Unlike crusades in the Holy Land, which were theoretically about reclaiming Christian territory, this crusade was overtly a war of conversion or extermination. Bernard of Clairvaux, in his letters to the crusaders, made the objective brutally clear:

We utterly forbid that for any reason whatsoever a truce should be made with these people, either for the sake of money or for the sake of tribute, until such a time as, by God’s help, either their religion or their nation shall be destroyed.

The slogan became “baptism or annihilation.” There was no middle ground. This directive transformed what might have been another regional border war into a holy mission of conquest and forced conversion, fueled by a potent mix of religious zeal, political ambition, and pure greed for land.

The Campaign of 1147

In the summer of 1147, a massive crusading force of perhaps 100,000 Germans, Danes, and Poles mustered. The leadership included some of the most powerful men in the region:

- Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony

- Albert the Bear, Margrave of the Northern March (soon to be Brandenburg)

- Kings Canute V and Sweyn III of Denmark (bitter rivals who briefly united for the cause)

The crusade split into two main thrusts. One army, led by Albert the Bear, marched on the Lutician stronghold of Demmin. Another, larger force co-led by Henry the Lion, laid siege to the Obotrite fortress of Dobin, ruled by a formidable Wendish prince named Niklot.

The crusaders, however, did not find the easy victory they expected. The Wends were fighting on their home turf. At the siege of Dobin, Niklot proved to be a brilliant and resilient commander. He launched devastating surprise attacks, including a sortie that annihilated a Danish contingent. Inside the fortress, the defenders famously taunted the besiegers by raising crosses, asking why the Christians were attacking fellow “followers” of the cross—a potent piece of psychological warfare against a divided enemy.

The crusaders’ motives were also far from pure. Several Saxon lords, including Henry the Lion, had previously received tribute from Niklot. A complete conquest would have ended this lucrative income stream. Suspicions arose that some leaders were dragging their feet, more interested in ravaging the countryside for plunder than in achieving a decisive victory. After weeks of frustrating stalemate, the siege of Dobin ended not with a bang, but a whimper. Niklot agreed to a mass baptism for his garrison and the release of some prisoners. The crusaders, weary and disunited, declared victory and went home.

The siege of Demmin met a similar fate, fizzling out without taking the fortress.

A Failure and a Turning Point

By any immediate measure, the Wendish Crusade of 1147 was a failure. The Wendish heartlands were not conquered. The mass “conversions” were symbolic at best, with most Wends reverting to their old faith as soon as the crusaders left. Niklot remained firmly in power, and the goal of “baptism or annihilation” was a distant fantasy. The campaign had devastated the land, but it hadn’t destroyed the Wendish people or their religion.

Yet, in the long run, the crusade was a pivotal turning point. It irrevocably changed the nature of the German-Slavic conflict. It established a precedent for religiously-sanctioned wars of expansion and colonization in the region—the beginning of the great German eastward expansion known as the Ostsiedlung.

The leaders of 1147, like Albert the Bear and Henry the Lion, would use the rest of their lives to expand their domains eastward, slowly but surely squeezing the Wends. Niklot himself would finally be defeated and killed by Henry the Lion in 1160. Over the following century, the old Wendish lands would be progressively conquered, Christianized, and settled by Germans. The Wendish Crusade may have failed in its immediate objectives, but it had opened the door to the eventual demise of the pagan Slavic west, forever reshaping the political and cultural map of Central Europe.