A Highway Forged by Power

While routes along Japan’s eastern coast had existed for centuries, it was the first Tokugawa shogun, Ieyasu, who formalized and standardized the Tōkaidō into a highway befitting his new, centralized government. After consolidating power and establishing his capital in Edo, he needed a way to control the country’s powerful feudal lords, the daimyō. His solution was a stroke of political genius: the sankin kōtai system, or “alternate attendance.”

This policy required every daimyō to journey to Edo and reside there for a year, then return to their own domain for the next. Their wives and heirs, however, were required to remain in Edo permanently as political hostages. This system served two brilliant purposes. First, it kept potential rivals under the shogun’s watchful eye. Second, the immense cost of maintaining two residences and funding the grand, bi-annual procession to and from the capital systematically drained the daimyō’s treasuries, preventing them from financing rebellions.

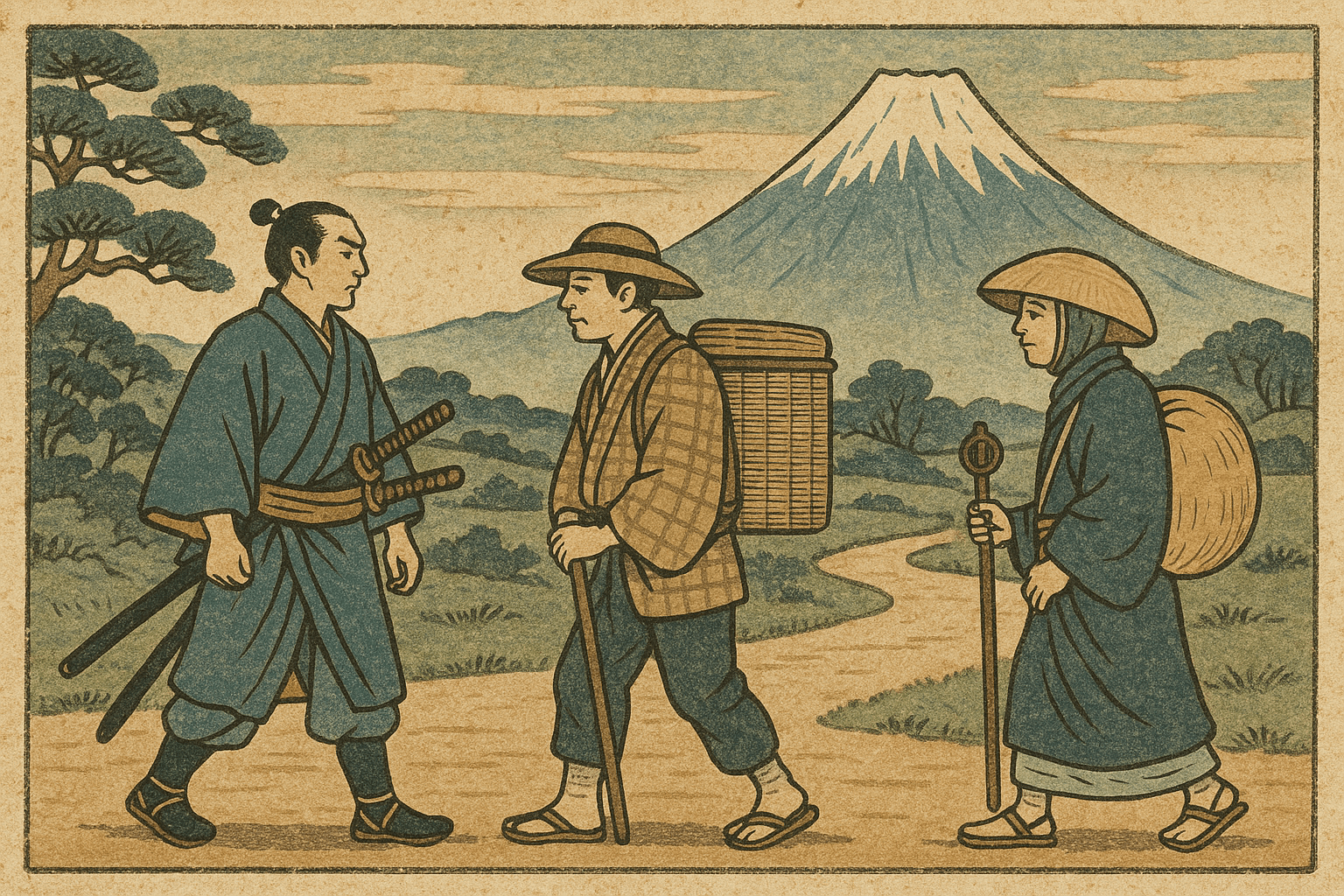

The Tōkaidō was the primary route for these spectacular processions. A powerful lord’s retinue could include hundreds or even thousands of samurai, porters, and officials, forming a “river of silk and steel” that snaked for miles along the road. The journey was a public display of the daimyō’s wealth and status, governed by strict etiquette and immense logistical challenges. For the shogun, these mandatory journeys turned the Tōkaidō into an instrument of control and a constant reminder of who held ultimate authority.

The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō

A journey of this length on foot or by palanquin could take weeks. To accommodate the constant flow of travelers, the shogunate established 53 official post stations, or shukuba, along the road. These stations, spaced a few hours’ walk apart, were bustling micro-cities dedicated entirely to the business of travel. Starting at Nihonbashi (“Japan Bridge”) in Edo and ending at Sanjō Ōhashi in Kyoto, each station offered a vital respite for weary travelers.

Within a typical shukuba, a traveler would find a stratified system of services:

- Honjin: Luxurious inns designated for daimyō and the highest-ranking court officials. These were often the private residences of the local mayor or an important family, opened exclusively for elite travelers.

- Waki-honjin: “Sub-honjin”, used as overflow for the daimyō’s retinue or for slightly less exalted officials.

- Hatago: General inns for common travelers, including lower-ranking samurai, merchants, and pilgrims. Here, you would find shared rooms, simple meals, and a lively atmosphere.

- Chaya: Teahouses offering rest, refreshments like tea and rice cakes (mochi), and often a scenic view.

- Porter Stations: Here, travelers could hire fresh porters (ninsoku) and horses to carry their baggage and themselves to the next station.

From the treacherous mountain pass at Hakone, where a government checkpoint meticulously inspected all travelers for “incoming guns and outgoing women” (a measure to prevent rebellions and daimyō wives from escaping), to the scenic shores of the Pacific, each station had its own unique character, local foods, and famous sights.

A Crossroads of Culture and Commerce

While the daimyō processions were the most spectacular sights on the road, they were far from its only users. The extended peace of the Edo period, a Pax Tokugawa, led to an explosion in domestic travel and trade. The Tōkaidō became a vibrant crossroads where every level of Japanese society mingled.

Merchants became a powerful class, using the road to transport goods like sake from Nara, textiles from Kyoto, and woodblock prints from Edo, creating a truly national economy for the first time. Pilgrims journeyed in vast numbers to famous religious sites like the Grand Shrine of Ise, which often required a detour from the main road. Itinerant monks, messengers, and government officials were a constant presence. Even commoners, with newfound leisure and disposable income, began traveling for pleasure, a concept almost unheard of in previous eras of civil war.

This great migration of people captured the imagination of artists. The most famous chronicler of the Tōkaidō was the ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Hiroshige. His print series, The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (1833-34), became an overnight sensation. His breathtaking and often intimate depictions of the landscapes, weather, and people along the road—from a sudden downpour at Shōno to the snow-covered evening in Kanbara—were not just art; they were souvenirs and travel guides. They allowed people who had never left their home village to experience the journey, cementing the Tōkaidō in the nation’s collective consciousness.

The Highway’s Enduring Legacy

The Tōkaidō did more than move people; it unified a nation. As travelers from every province met in the inns and teahouses, regional dialects, customs, and fashions began to blend. The sophisticated urban culture of Edo—the world of Kabuki theater, sumo wrestling, and popular literature—spread along the road, while the road in turn brought regional products and stories back to the capital.

The traditional Tōkaidō, as a foot highway, saw its decline with the Meiji Restoration in 1868. The new government, eager to modernize, dismantled the sankin kōtai system and soon laid Japan’s first railway line along the same coastal corridor. The age of the train had begun.

Yet, the Tōkaidō never vanished. Its legacy is etched into the modern Japanese landscape. Today, the Tōkaidō Shinkansen, the world’s first “bullet train”, and the Tōmei Expressway, a major automobile artery, follow the same historic path. They continue to serve as Japan’s primary economic and cultural corridor, connecting its largest metropolitan areas. The ancient highway of shoguns, samurai, and pilgrims has evolved, but its spirit endures as the timeless lifeline of Japan.