More than just a dwelling, the longhouse was a microcosm of Viking Age society. It was a home, a fortress, a workshop, and a stage for the dramas of life, death, politics, and celebration. Within its long, timber-framed walls, the complex social fabric of the Norse people was woven every single day.

A Home Built for a Community

The name “longhouse” is purely descriptive. These were immense structures, often stretching 50 to 250 feet in length, built with a sturdy timber frame and walls of wattle-and-daub, turf, or wood planks. They were typically windowless, with a single door at each end. Light and air came from the open hearths that ran down the center of the hall, with smoke escaping—or trying to—through simple openings in the thatched or turf roof.

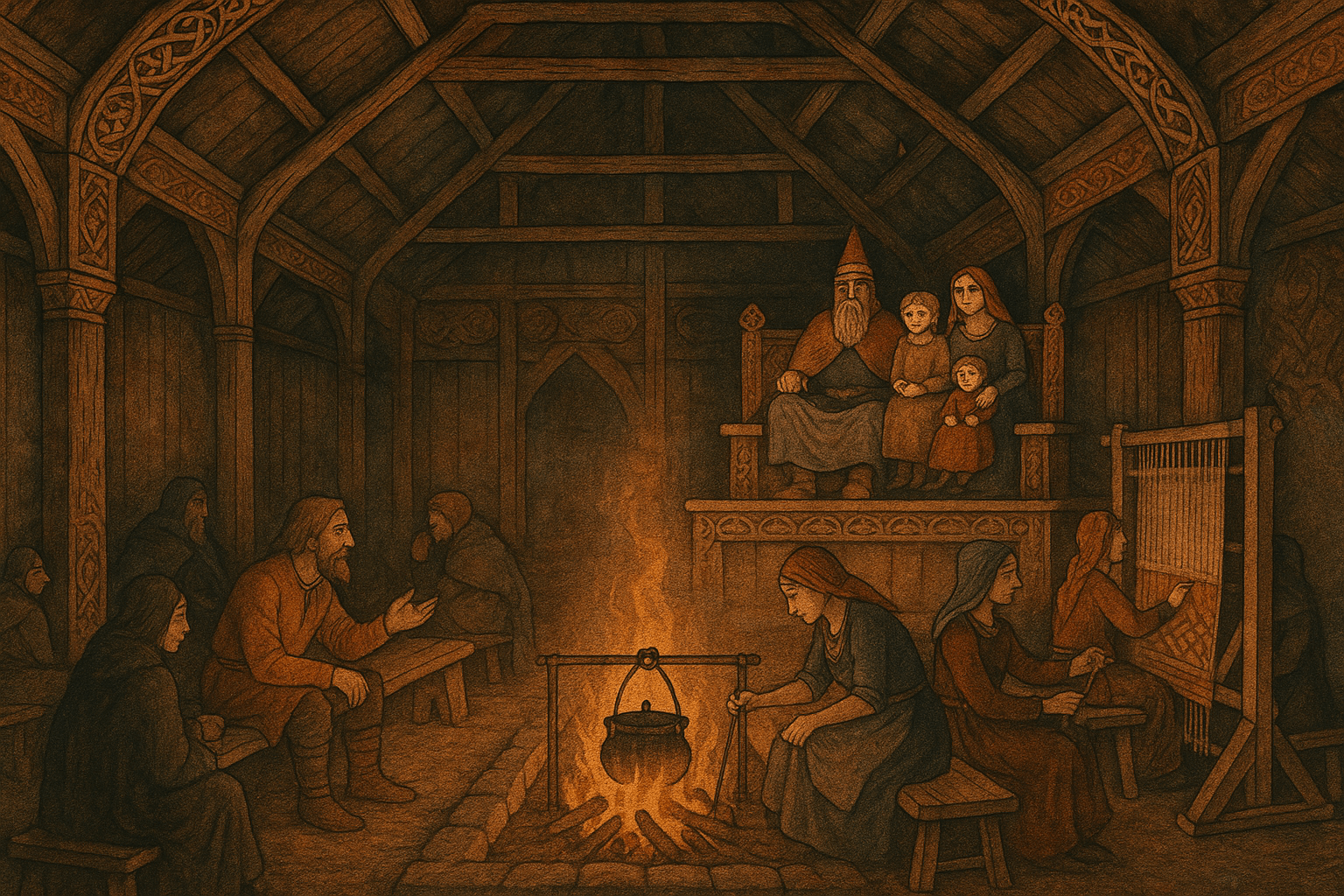

The interior was usually one vast, open room. The layout was designed for communal living, not privacy. Along the sides were raised wooden platforms, which served as benches for sitting and working during the day and as beds at night. Families would have their own designated section of the platform, but there were no walls or partitions. This open-plan living meant that every argument, every laugh, every birth, and every death was a semi-public event.

In many longhouses, particularly during the harsh Scandinavian winters, one end of the building was partitioned off to house valuable livestock. Bringing the animals inside protected them from predators and the cold, and their body heat provided an extra source of warmth for the human inhabitants.

The Social Ladder Under One Roof

The seating arrangement along the benches was a clear map of the household’s social hierarchy. Everyone had their place, and that place was determined by status, gender, age, and relationship to the head of the household.

The key figures were:

- The Head of the Household (Húsbóndi): The master of the house, be he a wealthy farmer (karl) or a powerful chieftain (jarl), held the most authority. He sat in the “high seat” (hásæti), usually in the middle of one of the long benches. From this seat of honor, he dispensed justice, hosted guests, and presided over feasts. His power came with responsibility; he was expected to provide for, protect, and ensure the prosperity of his entire household.

- The Lady of the House (Húsfreyja): The chieftain’s wife was a formidable figure in her own right. She held the keys to the locked food chests and storage rooms, a powerful symbol of her control over the household’s resources. The húsfreyja managed the entire domestic sphere: food production, weaving textiles, brewing ale, and overseeing the work of other women and thralls. She was the manager, not a servant.

- Family and Retainers: Close relatives—sons, daughters-in-law, and grandchildren—sat nearest the high seat. For a chieftain, this group also included his sworn warriors, or hird. These free men pledged their loyalty and fighting prowess in exchange for food, shelter, and a share of treasure. They were an integral part of the household’s strength and prestige.

- Thralls (Slaves): At the lowest end of the social ladder, and seated furthest from the high seat near the doors, were the thralls. Acquired through raids, debt, or born into servitude, thralls performed the most grueling labor: mucking out animal stalls, grinding grain, and serving the free members of the household. Their lives were hard and offered little autonomy, though some could eventually earn or be granted their freedom.

The Rhythm of Daily Life

Life in the longhouse was governed by the seasons and the sun. The day began early, with the family waking on their fur-lined benches. Chores were divided along gender lines. Men’s work was typically outside: farming the fields, tending livestock, hunting, fishing, or felling timber. For a chieftain and his retinue, it might also involve maintaining weapons and planning for trade or raids.

Women’s work centered on the “inside-yard” (innangarðs). Their day was a constant cycle of tasks essential for survival. They would grind grain to make porridge (grautr) and flatbread, churn milk into butter and skyr (a type of yogurt), and tend the kitchen garden. One of their most vital and time-consuming jobs was textile production—spinning wool into yarn and weaving it into cloth on large, warp-weighted looms for sails, blankets, and clothing.

The Hall of Stories and Songs

As darkness fell, the longhouse transformed. With the day’s labor done, the entire household would gather around the warmth and light of the central fires. This was the time for community, culture, and entertainment. In a world without widespread literacy, oral tradition was everything.

This was when the skalds, or court poets, would take center stage. They would recite epic poems about the daring deeds of legendary heroes like Sigurd the Dragon-slayer or the complex family dramas of the Norse gods—Odin, Thor, and Loki. These stories were not just entertainment; they were a way of passing down history, morality, and cultural identity from one generation to the next. The sagas, later written down in Iceland, were born in the smoky atmosphere of these halls.

Music from a lyre or flute might drift through the hall, and the clatter of game pieces was a common sound. Vikings were fond of board games, especially Hnefatafl (“King’s Table”), a strategic game of attack and defense that honed the mind for warfare. Of course, no evening was complete without feasting and drinking. Hospitality was a sacred duty, and a chieftain’s honor was measured by his ability to throw lavish feasts. Great quantities of ale and mead were consumed from drinking horns, strengthening the bonds between a leader and his followers.

The longhouse was the crucible of Viking society. It was a single space that contained the entire spectrum of life—the power of a chieftain, the authority of a matriarch, the loyalty of a warrior, and the toil of a thrall. It was where deals were struck, children were raised, gods were honored, and the stories that define the Viking Age were told. Far more than a home, the longhouse was the world in miniature.