Imagine the scene: the English Civil War is raging, and after a long, brutal siege, your forces have finally captured a formidable enemy castle. The Royalist banner is torn down, and the Parliamentarian flag is raised. The stronghold is yours. But what now? To occupy it requires a large garrison of soldiers, men who are desperately needed on the battlefield. Leave it empty, and the enemy might reclaim and refortify it. The solution for Parliament was often as brutal as it was practical: a strategy known as ‘slighting’.

Slighting was the deliberate, systematic demolition of a fortress to render it militarily useless. It was not wanton vandalism or a frenzied act of destruction in the heat of victory. It was a calculated policy of architectural sabotage, designed to permanently neutralize a threat and reshape the political landscape of the nation.

More Than Just Knocking Down Walls

The term ‘slighting’ comes from the idea of making something ‘slight’ or of little consequence. The goal was rarely to level an entire castle to the ground – an incredibly expensive and time-consuming task. Instead, it was a form of strategic demolition that targeted a castle’s key defensive features. The aim was to make it impossible to defend without a complete and costly rebuild.

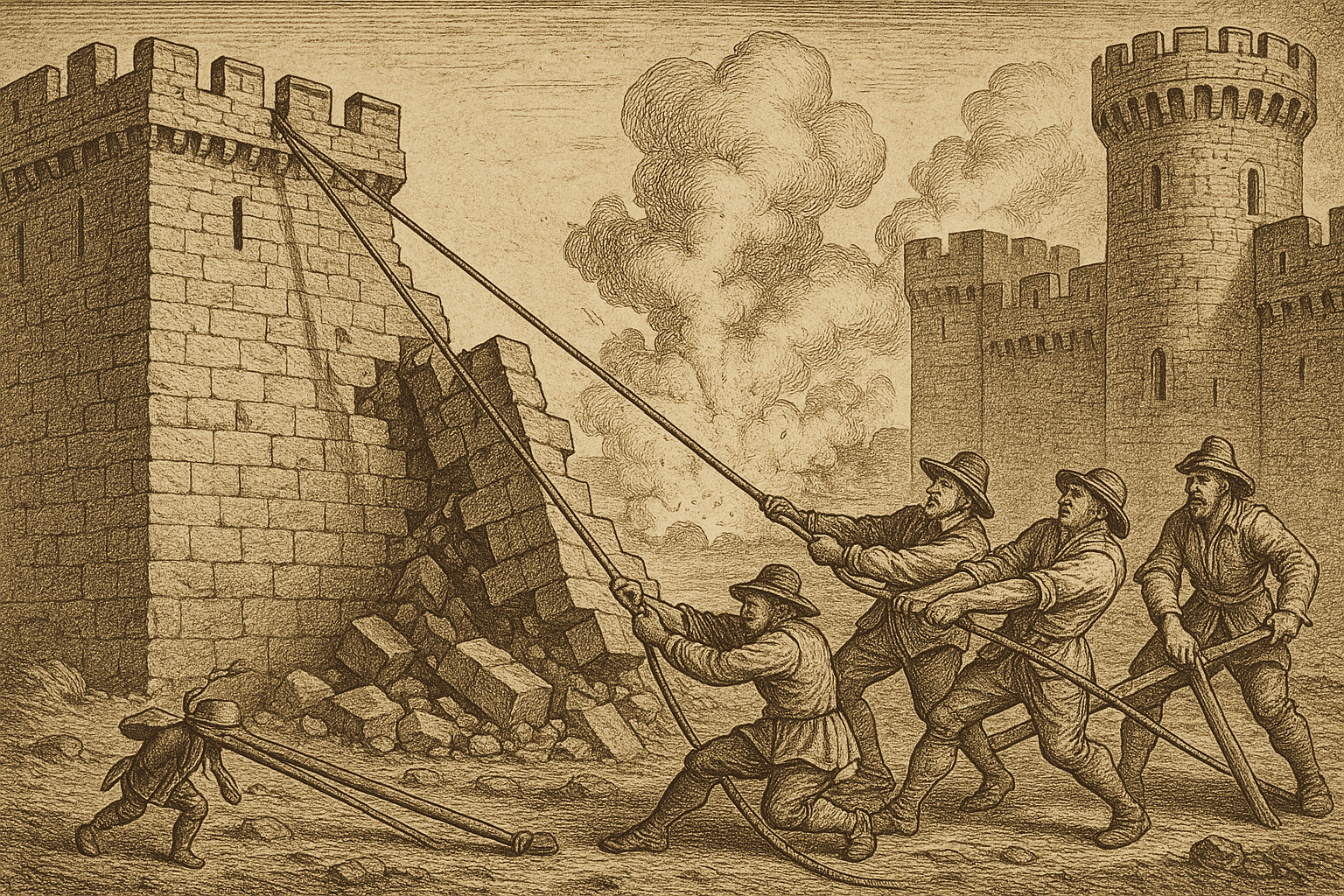

Specialist teams of engineers and labourers, sometimes called ‘pioneers’, would be dispatched with a clear set of orders. Their methods were methodical and effective:

- Undermining: Sappers would dig tunnels, known as mines, under key structures like a corner tower or a section of the curtain wall. These tunnels were propped up with timber beams. Once complete, the props would be set on fire, causing them to collapse and bringing the wall crashing down with them.

- Gunpowder: Where available, gunpowder was the tool of choice for maximum damage. Holes were drilled into the base of thick walls, packed with barrels of powder, and detonated. This could tear massive breaches in even the most formidable stonework.

- Manual Demolition: For less critical features, sheer manpower did the job. Teams with pickaxes, crowbars, and sledgehammers would tear down battlements, smash gatehouse mechanisms, fill in ditches (moats), and pull down the tops of towers.

The process was surgical. A slighted castle was left as a broken shell, its strength stolen, its purpose nullified. It could still be a residence, but it could no longer be a fortress.

A Parliamentarian Policy of Control

While both Royalists and Parliamentarians used slighting, it became a cornerstone of Parliamentarian strategy as the war progressed. As Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army gained control over vast swathes of England and Wales, they were faced with a strategic dilemma: how to control hundreds of castles, forts, and fortified manor houses that had been Royalist nests?

Garrisoning them all was a logistical nightmare. It would tie up tens of thousands of soldiers who were needed for the field army. A small garrison was vulnerable to recapture, while a large one was a waste of resources. Slighting provided the perfect solution. A small team could neutralize a castle in a matter of weeks, freeing up the army to move on.

In 1646, Parliament established a “Committee for the Demolition of Castles”, which formalized the process. Decisions were made not on the battlefield, but in London. This was more than just military pragmatism; it was deeply political. Castles were the ultimate symbols of the old feudal order and the power of the regional aristocratic lords who overwhelmingly supported the King. By demolishing their fortresses, Parliament was symbolically tearing down their power and authority, asserting the central control of a new kind of state.

Case Studies in Destruction

The romantic ruins that dot the British landscape today are often the direct result of this violent policy. Each broken tower and shattered wall tells a story of Civil War conflict.

Corfe Castle, Dorset: Perhaps the most iconic victim of slighting. This magnificent Royalist stronghold was heroically defended by Lady Mary Bankes before finally falling to Parliamentarian trickery in 1646. Determined it should never again threaten their control of Dorset, Parliament’s orders were explicit. Engineers spent weeks drilling holes and laying charges. The resulting explosions shattered the gatehouse and keep, causing huge sections of the towers to slide down the hill, where they rest today at jarring, impossible angles.

Pontefract Castle, Yorkshire: Known as the ‘Key to the North’, Pontefract endured three major sieges and was one of the strongest Royalist fortresses in the country. It was the last to surrender, holding out even after the execution of King Charles I in 1649. After its final, bitter capture, the local townspeople—weary of the constant warfare on their doorstep—actually petitioned Parliament for the castle to be demolished. The request was granted, and the once-mighty fortress was systematically dismantled, leaving only fragments behind.

Raglan Castle, Wales: A luxurious late-medieval palace-fortress, Raglan was the last castle in England and Wales to hold out for the king. After a lengthy siege in 1646, Sir Thomas Fairfax accepted the surrender of the Marquess of Worcester. The articles of surrender were honourable, but they did not protect the castle itself. Fairfax’s engineers set to work on the colossal Great Tower, undermining its foundations and leaving a massive, gaping wound that effectively destroyed the castle’s defensive heart.

The Scars on the Landscape

The end of the English Civil War marked the end of the castle’s relevance as a military installation in Britain. The slighting program was the final nail in its coffin. The widespread use of powerful artillery had already made traditional medieval designs obsolete, but this deliberate policy of destruction ensured they could never be revived.

Today, when we walk among these beautiful, broken ruins, it’s easy to imagine them as victims of time, slowly crumbling into picturesque decay. But the reality is far more violent. These are not just ruins; they are scars. They are the carefully preserved monuments of a brutal and efficient military strategy, testament to a time when gunpowder and politics were used to deliberately erase the power of the past from the landscape, forever.