The Aftermath of a “Great” War

To understand the fury of Sette Giugno, we must look at the world of 1919. The First World War was over, but the peace was fragile and the economic fallout was devastating. For the British colony of Malta, the war had been a period of artificial boom. Its Grand Harbour was a critical base for the Allied naval effort, and its dockyards worked tirelessly. But with the armistice, the work dried up. Thousands of Maltese workers were laid off, their wartime wages replaced by uncertainty and poverty.

Compounding the unemployment was a crippling food crisis. As a fortress colony with limited agricultural land, Malta was almost entirely dependent on imported grain. During the war, shipping was disrupted, and after the war, the British Empire prioritized feeding its own population in the UK. This led to severe shortages on the island. The little grain that did arrive was controlled by a handful of wealthy importers, known pejoratively as the tal-ħobż (“the bread people”). These merchants were accused of hoarding grain and colluding to inflate the price of bread to astronomical levels, all while the general population starved.

The social fabric was tearing apart. A stark and visible divide emerged between the struggling Maltese masses and the wealthy, often pro-British, elite and the British servicemen who enjoyed a far better standard of living. This economic hardship was the dry tinder. The political frustration was the spark.

A Political Awakening

For decades, Maltese intellectuals and professionals had been campaigning for greater political autonomy. The existing “Council of Government” was largely a sham, with Maltese representatives having little real power against the British colonial administration. By 1919, a National Assembly had been formed to draft a new, more representative constitution, demanding self-governance in local affairs.

The Assembly was scheduled to meet on Saturday, June 7, 1919. For the people gathering in the capital, Valletta, that morning, the meeting represented a flicker of hope. But hope was overshadowed by the immediate, gnawing pain of hunger. The crowd was a volatile mix of dockyard workers, students, and ordinary citizens whose patience had finally run out.

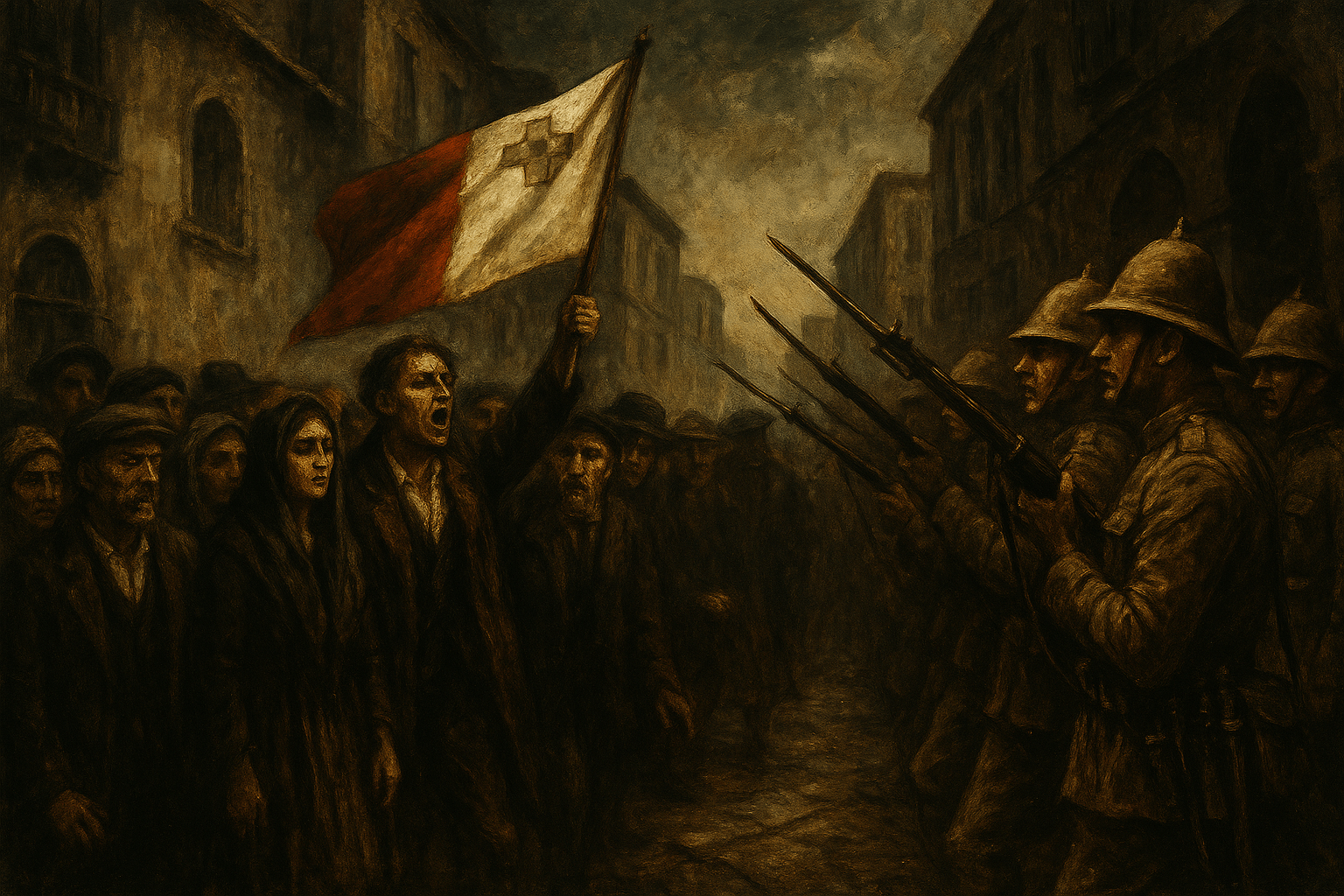

The Spark Ignites Valletta

The protest began with a symbolic act. A Maltese flag appeared on the flagpole of a club, and as the crowd swelled, a Union Jack was torn from the “A la Ville de Londres” building. The target of the people’s rage was clear: not just the colonial power, but the local merchants perceived as collaborators and war profiteers. The offices of a grain importer were ransacked, furniture and records hurled into the street. The home of another wealthy merchant, whose family owned the flour mills, was attacked.

The colonial police were overwhelmed. As the situation spiraled, the local British military commander made a fateful decision. Around 100 soldiers were deployed to quell the unrest. They were a menacing presence, but initially, they held back. However, as the rioters began to target the homes of pro-British figures, including the newspaper editor who opposed self-rule, the troops were ordered to protect the properties.

In the chaos in front of one of these houses, a confrontation occurred. A marine panicked or was given an order. A shot rang out. Then another. When the smoke cleared, three Maltese men lay dead or dying:

- Manwel Attard

- Ġużè Bajada

- Lorenzo Dyer

The sound of gunfire turned a riot into a national tragedy. The crowd, now horrified and enraged, carried their fallen comrades through the streets. The day’s events had irrevocably crossed a line from protest to rebellion.

The Aftermath and Lasting Legacy

The unrest continued into the next day. On June 8th, a mob attacked the palace of Colonel Francia, another wealthy merchant. Soldiers again opened fire, and a fourth man, Carmelo Abela, was killed while trying to defend the front door of the palace which the mob was trying to set on fire.

In response, the British authorities declared martial law. Censorship was imposed, and dozens of Maltese were arrested and sentenced to prison. A Commission of Inquiry was established, which, while placing blame on the rioters, also acknowledged the immense economic hardship caused by the grain situation as the root cause.

But the blood spilled on the streets of Valletta could not be washed away or ignored. The Sette Giugno massacre was a profound shock to the colonial administration in London. It demonstrated, in the most brutal way possible, that the Maltese situation was untenable. The calls for political reform could no longer be dismissed as the chatter of a few elites; it was now the demand of a people who had paid for it in blood.

The riots were the violent catalyst that forced London’s hand. In 1921, the British government granted Malta the Amery-Milner Constitution. It established a bicameral legislature with a Senate and a Legislative Assembly, giving Malta responsible self-government in domestic matters for the first time. While defense and foreign affairs remained in British hands, it was a monumental step forward.

Conclusion: A Nation Forged in Hunger and Grief

Today, Sette Giugno is a national holiday in Malta. In Valletta’s St. George’s Square, a monument depicts figures representing the uprising, a permanent memorial to the four men who died. The event is remembered not as a simple riot, but as a pivotal sacrifice in the nation’s struggle for sovereignty.

The story of Sette Giugno is a powerful, localized example of a global theme. It shows how imperial power, economic exploitation, and social inequality can combine to create an explosive situation. More importantly, it demonstrates how the very basic, visceral struggle for survival—the fight for a loaf of bread—can ignite a powerful nationalist movement and set a nation on the path to freedom. It’s a somber reminder that the grand arc of history is often bent by the hands of ordinary people pushed to their absolute limit.