When we picture classical Japan, the image of the samurai often comes first to mind: a stoic warrior clad in ornate armor, wielding a razor-sharp katana, and living by a strict code of honor. They are the quintessential symbols of a feudal society, the ruling military elite who governed Japan for centuries. But this image represents the samurai at the height of their power, not at their inception. They were not born into dominance.

The story of the samurai is a story of ascension—a gradual, often bloody, climb from the fringes of society to its very center. Their journey from provincial guards to the de facto rulers of Japan is a pivotal chapter in world history, illustrating how power vacuums are filled and how social structures can be completely reshaped by the sword.

Servants of the Court: The Heian Period (794–1185)

To find the origins of the samurai, we must travel back to the Heian period, an era renowned for its extraordinary cultural achievements. In the capital, Heian-kyō (modern-day Kyoto), the imperial court, led by the Emperor and dominated by the powerful Fujiwara clan, reached a pinnacle of aristocratic refinement. Life was a whirlwind of poetry contests, elaborate ceremonies, and intricate courtly romance, famously captured in “The Tale of Genji.”

However, while the nobility in the capital were composing verse, the foundations of their power in the provinces were crumbling. The central government’s authority barely extended beyond Kyoto. They outsourced the management of their vast, tax-exempt rural estates, known as shōen, and neglected the state’s military institutions. This created a dangerous power vacuum. Bandits roamed the countryside, and disputes between landowners frequently erupted into violence.

Who was there to protect these estates and enforce order? Not the imperial army, which had fallen into disuse. Instead, provincial nobles and estate managers began to hire armed retainers to protect their interests. These early warriors were known as bushi (a general term for a warrior) and their defining characteristic was service. In fact, the word samurai itself derives from the verb saburau, which means “to serve.” They were, in essence, the armed security and enforcers for an absentee aristocracy.

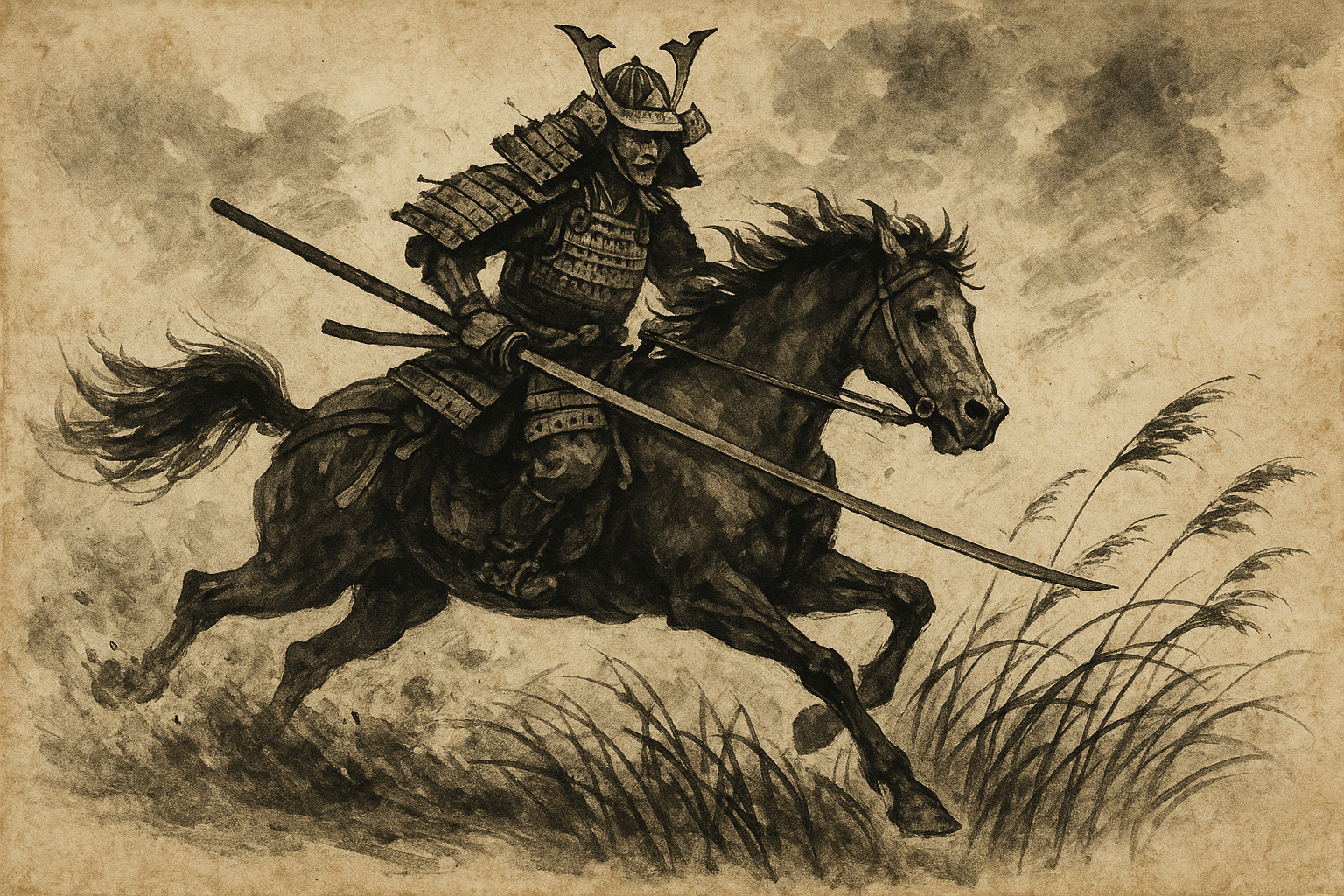

These early warriors were a far cry from the later romanticized figures. They were rugged, practical fighters, primarily mounted archers whose skills were honed in the harsh realities of provincial skirmishes. Their loyalty was not to the distant, divine Emperor, but to the local lord who paid them, fed them, and led them in battle.

The Rise of the Great Warrior Clans

As the central government’s influence continued to wane, these provincial warrior bands grew in strength and organization. They coalesced around powerful families, forming large, formidable clans bound by blood, marriage, and sworn loyalty. From the multitude of these lesser warrior families, two great clans emerged to dominate the military landscape: the Taira (also known as the Heike) and the Minamoto (or Genji).

Both clans had prestigious origins, tracing their lineage back to emperors who had demoted their sons to commoner status to ease the strain on the imperial purse. Stripped of their imperial rank, these descendants sought their fortunes not in the perfumed halls of the court, but in the untamed provinces. By the 11th and 12th centuries, the Taira and Minamoto had become the court’s go-to problem solvers, called upon to suppress rebellions and pirates that the state could no longer handle on its own.

In a twist of dramatic irony, the imperial court itself began to use these warrior clans to settle its own political disputes. The Hōgen Rebellion (1156) and Heiji Rebellion (1160) saw factions within the court call upon the Minamoto and Taira to fight on their behalf. These conflicts brought provincial warfare directly into the streets of the capital. While the court nobles believed they were using the warriors as pawns, the warriors were learning a valuable lesson: their military might was the true source of power in Japan.

The Genpei War: A Nation Engulfed in Flame (1180–1185)

After the Heiji Rebellion, the Taira clan, led by the ambitious Taira no Kiyomori, emerged victorious. Kiyomori cleverly integrated his family into the imperial court, marrying his daughter to the emperor and eventually placing his own infant grandson on the throne. The Taira effectively became the new power behind the chrysanthemum throne, enjoying the wealth and prestige that came with it. They had made the leap from provincial warriors to court rulers.

Their dominance, however, was resented. In 1180, a spurned imperial prince called upon the defeated Minamoto clan to rise up against the Taira. What followed was the Genpei War, a five-year-long nationwide civil war that definitively ended the classical era of courtly rule.

The war was a brutal, sprawling conflict that pitted the Taira’s court-based power against the rugged, provincial warrior base of the Minamoto, led by Minamoto no Yoritomo. It was a clash that cemented the samurai ethos, immortalizing tales of heroism, strategy, and sacrifice. The war culminated in 1185 at the naval Battle of Dan-no-ura, where the Minamoto fleet annihilated the Taira. The Taira clan, along with the child Emperor Antoku, were drowned in the unforgiving sea.

The Kamakura Shogunate: A New Order is Born

With his rivals utterly destroyed, Minamoto no Yoritomo stood as the most powerful man in Japan. But he was a shrewd and patient politician, not just a warrior. He understood that the emperor, descended from the sun goddess Amaterasu, held a sacred authority that could not be usurped. To rule in Japan, one needed legitimacy, and legitimacy flowed from the throne.

So, Yoritomo did something brilliant. He left the emperor and his court in Kyoto, preserving their ceremonial and religious functions. He then established his own capital and seat of government far away in Kamakura, a small coastal town in eastern Japan. This new military government was called the bakufu, or “tent government”, a name that reflected its martial origins. In 1192, a reluctant emperor granted Yoritomo the title of Seii Taishōgun, or “Great Barbarian-Subduing Generalissimo.”

This act formally established the Kamakura Shogunate and created a dual system of government that would last for nearly 700 years.

- The Emperor in Kyoto: The divine, symbolic source of all legitimacy and sovereignty.

- The Shogun in Kamakura: The de facto ruler, holding all military, administrative, and political power.

The rise of the samurai was complete. No longer were they mere servants. They were now the masters of Japan. The warrior class, born out of the practical needs of provincial security, had seized control of the state, establishing a new political and social order founded not on poetry, but on power. Their ascension forever changed the course of Japanese history, inaugurating an age where the way of the warrior—the way of the samurai—was the law of the land.