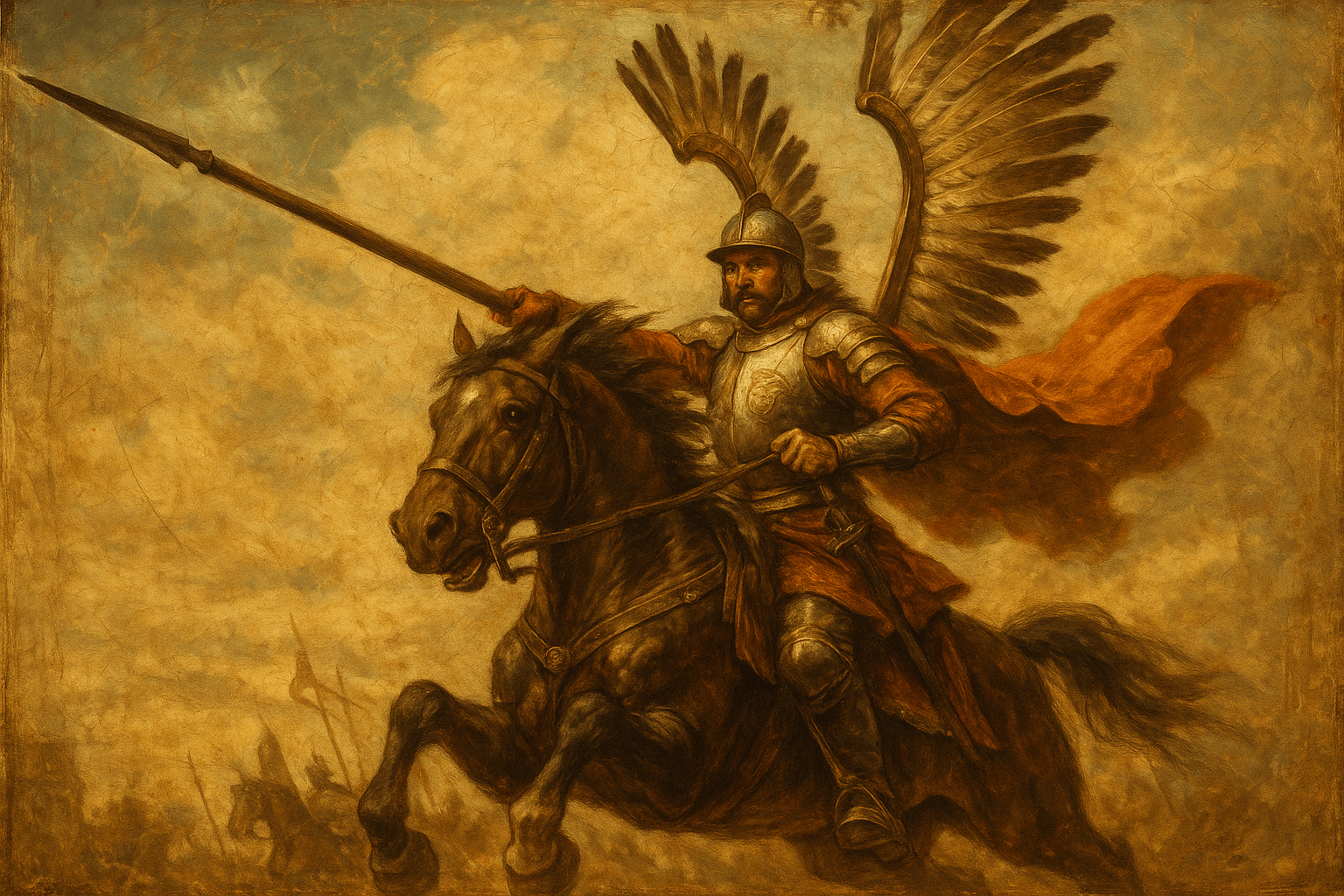

More than just soldiers, the Winged Hussars were a symbol of an era, an elite force of shock cavalry that dominated the battlefields of Eastern and Central Europe. Their story is one of transformation, devastating tactics, and a legendary last ride that saved a continent.

From Mercenaries to an Elite Force

The Hussars did not begin as the heavily armored knights of legend. Their origins lie with Serbian and Hungarian light cavalry mercenaries, known as gusars, who entered Polish service in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. These early hussars were equipped in the Balkan style, with light armor, a wooden shield, and a light lance. They were skilled horsemen, perfect for scouting and skirmishing against the mobile forces of the Ottoman Empire and Crimean Tatars.

The transformation into a heavy, decisive shock force came during the reign of King Stephen Báthory in the 1570s. Báthory, a brilliant military reformer, recognized their potential. He standardized their equipment, phasing out the old shields and introducing heavy plate-metal cuirasses for the torso. The hussar was no longer a light skirmisher; he was becoming the decisive hammer of the Polish army.

The Anatomy of a Winged Hussar

What made a Winged Hussar so effective was his unique combination of arms, armor, and training. Each nobleman (szlachcic) serving as a hussar was a one-man arsenal, responsible for his own incredibly expensive equipment and that of his retainers.

The Devastating Kopia

The hussar’s primary weapon was the kopia, a revolutionary type of lance. Unlike medieval lances, which were solid and heavy, the kopia was hollowed out, constructed from two pieces of wood glued together. This made it incredibly long—sometimes up to 20 feet—yet light enough to be wielded effectively. It was designed for one thing: impact. Tipped with a formidable steel point, the kopia could easily punch through the armor of a Western European pikeman or knight. Its length gave the hussar a crucial reach advantage over nearly all contemporary infantry and cavalry. These lances were designed to shatter on impact, ensuring the rider wasn’t unhorsed and could immediately draw a secondary weapon.

Weapons for the Melee

Once the lances were broken and the enemy line was shattered, the hussars would draw their other weapons to wreak havoc in the resulting melee. Their arsenal typically included:

- A koncerz: A long, straight, armor-piercing stabbing sword, often over five feet long, kept under the saddle. It was used like a lance to impale armored opponents.

- A szabla: The iconic Polish curved saber, renowned for its effectiveness in close-quarters combat from horseback.

- Pistols: One or two wheellock pistols were carried in saddle holsters for an extra shot before closing in.

- A nadziak: A type of war hammer or horseman’s pick, brutally effective at crushing helmets and armor.

The Famous Wings: Myth and Reality

No discussion of the hussars is complete without addressing their most iconic feature: the “wings.” These were wooden frames, adorned with the feathers of eagles, falcons, or vultures, which gave the hussars their unforgettable silhouette.

For decades, historians debated their purpose. Were they purely for ceremony? Did they make a terrifying noise to spook enemy horses? A popular but unfounded myth claimed they were designed to foil Tatar lassos. The reality is more practical and psychological. While early hussars attached wings to their saddles, the more famous back-mounted style became prevalent in the 17th century.

Their primary purpose was psychological warfare. The sight of a charging wall of winged warriors, appearing larger and more inhuman, was designed to terrify enemy infantry and break their morale before contact was even made. They also served a practical purpose in the chaos of battle, helping hussars identify each other and preventing their own horses from shying away from what appeared to be a unified, advancing mass. The soft rustling sound they made was likely drowned out by the thunder of a charge, but their visual impact was undeniable.

The Charge That Saved Vienna

The Winged Hussars won numerous victories against Swedes, Muscovites, and Ottomans, often while being vastly outnumbered. But their finest hour came on September 12, 1683, at the Battle of Vienna.

The Ottoman army had laid siege to the city, the gateway to Central Europe. A massive Christian relief army, commanded by Polish King Jan III Sobieski, assembled to break the siege. After a day of fierce fighting, Sobieski positioned his forces on the Kahlenberg heights overlooking the Ottoman camp.

In the late afternoon, he unleashed one of the largest cavalry charges in history. An estimated 18,000 horsemen, led by 3,000 Polish Winged Hussars under the king’s personal command, thundered down the slope. The hussars formed the tip of the spear. With their long kopias lowered, they smashed into the Ottoman lines. The impact was cataclysmic. The tired Ottoman troops, caught between the Vienna garrison and the charging relief army, broke and fled in panic. The siege was lifted, and the Ottoman Empire’s expansion into Europe was halted for good.

Decline and Enduring Legacy

The 18th century saw the sad decline of the Winged Hussars. The Commonwealth was weakening politically, and military technology was changing. The development of the flintlock musket and the ring bayonet allowed infantry to deliver devastating volleys of fire and then present a dense wall of steel, making cavalry charges increasingly suicidal. The immense cost of a hussar’s equipment also made the formation difficult to maintain in a state facing economic and political collapse.

The Winged Hussars were officially disbanded in 1776. Though their era had passed, their legacy endures. In Poland, they are a potent national symbol, representing a golden age of military prowess, courage, and a time when a Polish king and his winged knights rode to the salvation of Europe. They remain one of history’s most visually stunning and effective military formations, a thundering echo from a bygone age of warfare.