The Rule of Nature in a Mercantilist World

The name “Physiocrat” derives from the Greek for “rule of nature.” This was the core of their philosophy. Led by François Quesnay, the brilliant physician to King Louis XV’s influential mistress, Madame de Pompadour, the Physiocrats believed that the economy, like the human body, was governed by a natural order. If left to its own devices, it would function harmoniously and efficiently.

This directly challenged the dominant economic theory of the day: Mercantilism. Mercantilists believed a nation’s wealth was measured by its hoard of gold and silver. To get rich, a country had to export more than it imported, engaging in a cutthroat game of protectionist tariffs, colonial exploitation, and state-sponsored monopolies. The Physiocrats saw this as a fool’s errand. To them, piling up gold was like hoarding tokens; it wasn’t real wealth.

For the Physiocrats, real wealth was the “net product” (produit net) generated by nature. A farmer plants one seed and harvests a bushel of grain—that surplus is new wealth. A miner pulls ore from the earth—that is new wealth. In contrast, an artisan who carves a chair from a piece of wood or a merchant who sells wool at a market is not, in their view, creating anything new. They are merely transforming or transporting wealth that originated from the land. This made them part of the “sterile class.”

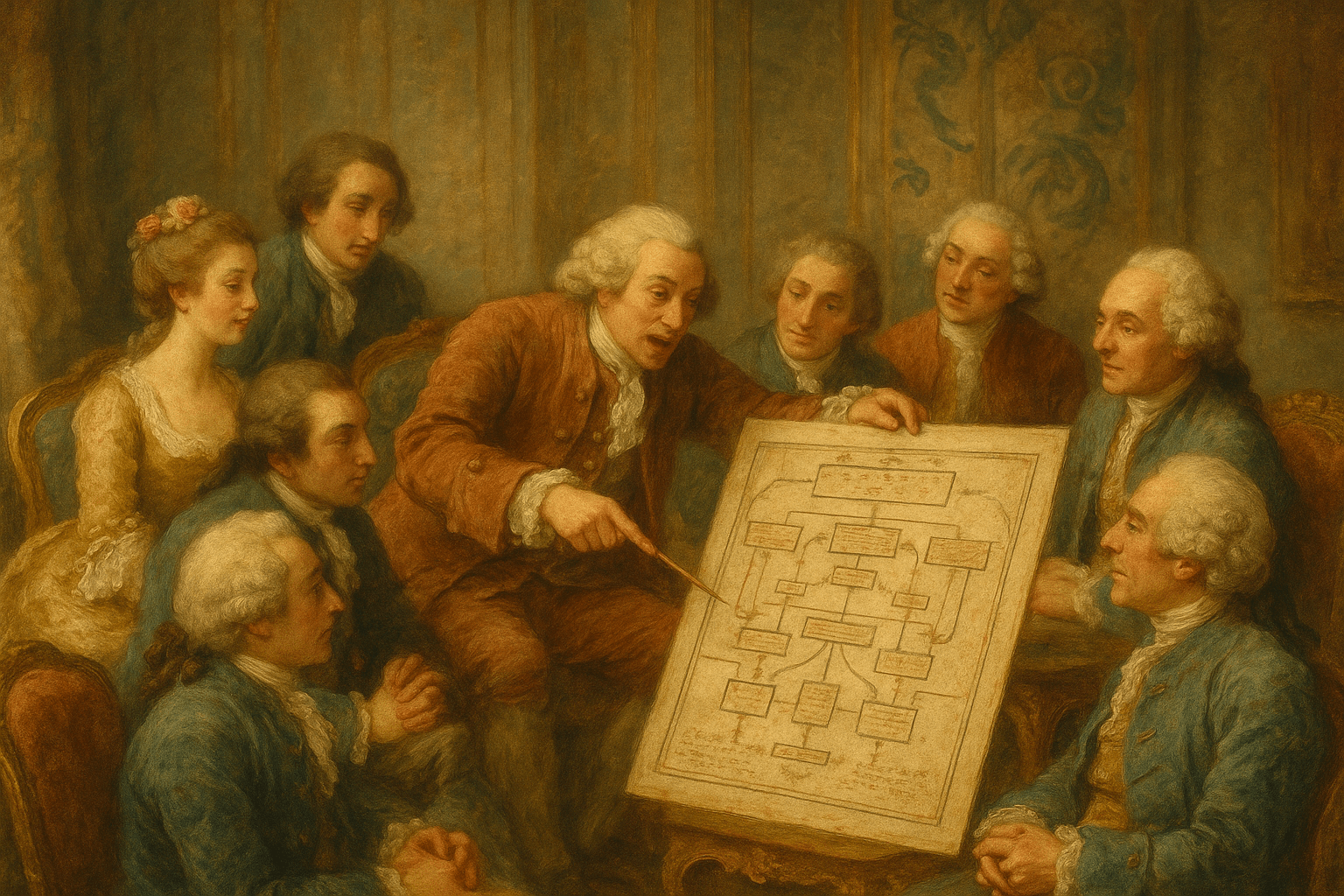

The Tableau Économique: A Doctor’s Diagram of the Economy

Quesnay’s medical background heavily influenced his economic vision. He saw the economy not as a static pile of treasure, but as a living, circulating system—much like the circulation of blood he had studied as a physician. To illustrate this groundbreaking idea, he created the Tableau Économique (the “Economic Table”) in 1758. It was the world’s first macroeconomic model.

The Tableau was a zigzagging diagram that showed how the agricultural surplus flowed through the different sectors of society. It divided society into three classes:

- The Productive Class: The farmers and miners who were the sole source of all real wealth.

- The Proprietary Class: The landowners, including the nobility, the Church, and the King himself. They contributed nothing to production but were essential because they owned the land and their spending (from rents received) helped circulate the wealth.

- The Sterile Class: Artisans, merchants, manufacturers, and professionals. While useful and necessary, the Physiocrats argued they merely reshaped or moved existing wealth and consumed agricultural goods without producing a net surplus.

The model demonstrated how the farmers’ surplus was paid as rent to the landowners, who then spent that money on both agricultural goods (food) from the Productive Class and finished goods (clothes, furniture) from the Sterile Class. The Sterile Class, in turn, used that income to buy food and raw materials from the farmers. The money had completed its circuit. For its time, this was a breathtakingly elegant and holistic vision of a national economy.

A Radical Prescription: Laissez-Faire and the Single Tax

From their diagnosis of the economy flowed a set of radical policy prescriptions, all summed up in their famous slogan: “Laissez-faire, laissez-passer” (“let do, let pass”). This was a direct assault on the micro-managing, regulation-heavy ethos of the French monarchy.

First, they argued for complete deregulation of the grain market. At the time, France was a patchwork of internal tolls, tariffs, and regulations that made it cheaper to ship grain to another country than to another French province. The Physiocrats argued for sweeping away these barriers and allowing free trade, believing it would ensure farmers got the best price for their goods and prevent regional famines.

Even more radically, they proposed a complete overhaul of the tax system. The French tax code under the Ancien Régime was notoriously unjust and inefficient, with the peasantry and middle class bearing the entire burden while the nobility and clergy—who owned most of the land—were largely exempt. The Physiocrats’ solution was the l’impôt unique, or the “single tax.”

Their logic was simple: since all wealth ultimately comes from the land’s surplus, all taxes should be levied at that source. They proposed a single, direct tax on land rents collected by the Proprietary Class. This would not only simplify the system but, in a revolutionary stroke, force the privileged, tax-exempt landowners to finally pay their share. This idea was, of course, wildly unpopular with the aristocracy.

The Physiocrats’ Lasting Legacy

The Physiocrats’ moment in the sun was brief. Their greatest hope, Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, a fellow traveler of the movement, became France’s finance minister in 1774. He tried to implement Physiocratic reforms—abolishing guilds, freeing the grain trade, and planning a land tax—but was swiftly defeated by entrenched interests at court and dismissed within two years. His failure exposed the monarchy’s inability to reform itself, pushing France further down the path to revolution.

Though their core theory was flawed—clearly, industry and services do create value—the Physiocrats’ influence was profound.

- They were the first to view the economy as a distinct, interconnected system governed by natural laws, laying the groundwork for modern economics.

- Their Tableau Économique was the direct ancestor of the circular flow diagrams found in every introductory economics textbook and the input-output models used by modern governments.

- Their cry of laissez-faire became the rallying cry for classical liberal economists for the next century.

Perhaps their most important contribution was the influence they had on a visiting Scotsman named Adam Smith. Smith met Quesnay and Turgot in Paris and was deeply impressed by their systematic thinking and criticism of mercantilism. While he rejected their notion that land was the sole source of wealth, he praised their system highly in The Wealth of Nations:

“This system, however, with all its imperfections, is, perhaps, the nearest approximation to the truth that has yet been published upon the subject of political economy.”

The Physiocrats were ultimately proven wrong on their central premise. But by being the first to ask the right questions and attempting to answer them with a logical, systematic framework, these forgotten French thinkers cleared the path for everyone who followed. They were the essential, if imperfect, first draft of modern economic thought.