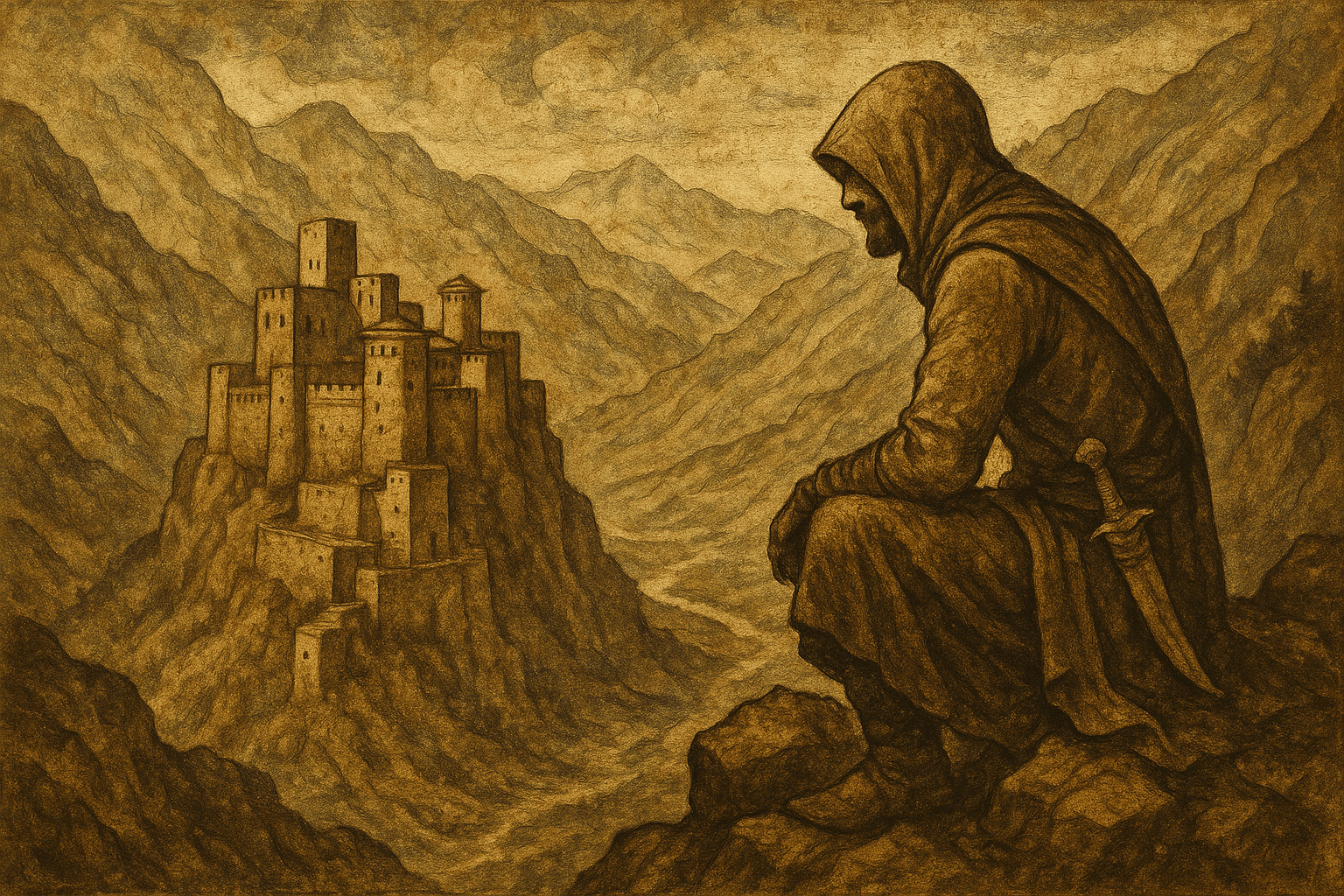

The word “assassin” conjures a vivid, romanticized image: a shadowy figure clad in black, emerging from the dark with a gleaming dagger, ready to sow terror and chaos. This image, popularized in video games and fiction, owes its existence to the legendary Hashashin of Alamut. For centuries, their story has been one of a mysterious death cult, of young men drugged with hashish and lured by promises of a secret paradise, transformed into mindless killers for their master, the “Old Man of the Mountain.”

But what if this sensational tale is just that—a tale? What if the truth is far more complex and fascinating? The story of the Nizari Ismailis of Alamut is not one of a drug-fueled cult, but of a sophisticated political and intellectual movement that used surgical strikes as a desperate, yet brilliant, tool for survival in a hostile world.

The Birth of a State: Who Were the Nizari Ismailis?

To understand the “Assassins”, we must first travel back to the 11th century Middle East. They were not a random cult but a sect of Shia Islam known as the Ismailis. A major succession crisis in 1094 within the Cairo-based Fatimid Caliphate split the Ismailis into two factions. Those who supported the caliph’s elder son, Nizar, became the Nizari Ismailis. Persecuted and scattered, they were a minority within a minority, surrounded by the staunchly Sunni Seljuk Empire.

Enter Hassan-i Sabbah. A brilliant theologian, strategist, and revolutionary from Persia, Hassan became the visionary leader the Nizaris needed. He wasn’t a mystical cult leader but a pragmatic state-builder. He recognized that for his community to survive, it needed a secure, defensible base from which it could resist the overwhelming military might of the Seljuks. He found that base in the unlikeliest of places: a fortress called Alamut.

Alamut: The Eagle’s Nest

Perched high in the inaccessible Elburz Mountains of modern-day Iran, Alamut, or the “Eagle’s Nest”, was the perfect headquarters. But Hassan-i Sabbah didn’t storm its walls with an army. In a move that would define his movement, he took it through infiltration. Over several years, his missionaries converted the garrison and the surrounding villagers. By the time the Seljuk lord of the castle realized what was happening, the fortress was ideologically Hassan’s. In 1090, he was let inside and the fortress was his without a single drop of blood being shed.

Under Nizari rule, Alamut was transformed. It became the capital of a unique “state” comprised of a network of similar mountain strongholds across Persia and Syria. More importantly, it was a major intellectual center. Hassan-i Sabbah established a magnificent library that drew scholars from across the region, housing priceless texts on science, philosophy, and theology. This was no den of killers; it was a vibrant hub of learning and devotion.

Deconstructing the “Hashashin” Myth

So where did the stories of drugs and paradise gardens come from? The term Hashashin (often translated as “hashish-users”) was a derogatory slur used by their enemies. There is no evidence from Nizari sources that they ever used this name themselves. The most famous account comes from the Venetian traveler Marco Polo, who wrote:

He had a chosen band of personal retainers whom he called his Ashishin… He had made, in a valley between two mountains, the biggest and most beautiful garden that was ever seen… and there he would place the youth, after having plied them with a certain potion that cast them into a deep sleep… When he awoke, he found himself in the garden… and he truly believed that he was in paradise.

The problem? Marco Polo traveled through the region in the late 13th century, more than 30 years after Alamut had been destroyed by the Mongols. He never met a Nizari from Alamut and was almost certainly repeating hostile, second-hand propaganda. From a purely logical standpoint, the story makes no sense. The elite agents, known as fida’i (“one who sacrifices”), carried out complex, long-term missions that required immense discipline, patience, language skills, and mental clarity. Drugging them into a stupor would have been the worst possible way to prepare them for such tasks.

The “paradise garden” was likely a symbolic allegory for the spiritual bliss promised in Ismaili theology, a concept their enemies twisted into a literal, drug-induced hallucination to dehumanize them.

The Real Weapon: Psychological Warfare and Surgical Strikes

Unable to field an army that could match the Seljuks, Hassan-i Sabbah developed a strategy of asymmetric warfare. The Nizaris’ true weapon was not a legion of drugged killers, but the targeted, political assassination of key enemy leaders. These were not random acts of terror; they were calculated “surgical strikes” designed to achieve specific political goals.

The fida’i were the instrument of this policy. They were highly trained, deeply devout followers willing to sacrifice their lives for their community. Their missions often involved infiltrating an enemy’s court or military camp for months, even years, waiting for the perfect moment to strike. Their primary targets were the figures who actively threatened the Nizaris’ existence:

- Nizam al-Mulk: The powerful Seljuk vizier and the Nizaris’ arch-nemesis, he was their first and most high-profile victim in 1092. His death destabilized the Seljuk Empire and served as a stunning declaration that the Nizaris were a force to be reckoned with.

- Conrad of Montferrat: The Crusader King of Jerusalem was assassinated in Tyre in 1192. This event cemented their fearsome reputation among the European Crusaders.

Often, the threat was more powerful than the act itself. In a famous episode, the great Sultan Saladin awoke to find a dagger stuck in the ground by his pillow, alongside a note with a clear warning. The Nizaris had proven they could get to anyone, anywhere. Terrified, Saladin promptly ceased his campaign against them and sought an alliance. This was psychological warfare at its most effective.

The Fall of the Eagle’s Nest

The Nizari state of Alamut survived for over 160 years, outlasting empires and dynasties. But it could not withstand the Mongol cataclysm. In the 1250s, the armies of Hulagu Khan swept across Persia, leaving devastation in their wake. After a prolonged siege, the last Nizari grandmaster, Rukn al-Din Khurshah, surrendered Alamut in 1256 in the hope of sparing his people.

Hulagu Khan, however, had no intention of leaving this legendary power base intact. He ordered the fortress to be systematically dismantled. Tragically, he also commanded that Alamut’s great library be burned to the ground. Centuries of Nizari Ismaili history, literature, and philosophy went up in smoke, leaving a void that would be filled by the dark legends of their enemies.

The story of the Nizari Assassins is a powerful reminder of how history is often written by the victors. The reality behind the myth is one of a persecuted community that, against all odds, carved out an existence through intelligence, devotion, and a ruthless pragmatism born of necessity. They were not a cult of brainwashed killers, but a sophisticated state that perfected the art of asymmetrical warfare to defend its people and its faith.