The Minoan civilization, which flourished on the island of Crete from approximately 2700 to 1450 BCE, was a sophisticated Bronze Age culture known for its sprawling palaces, vibrant art, and mysterious symbols. Among their most famous artistic legacies are the vivid frescoes that adorned the walls of palaces like Knossos. And it is here, frozen in plaster for over three millennia, that we find our primary evidence for bull-leaping.

Frozen in Fresco: The Visual Evidence

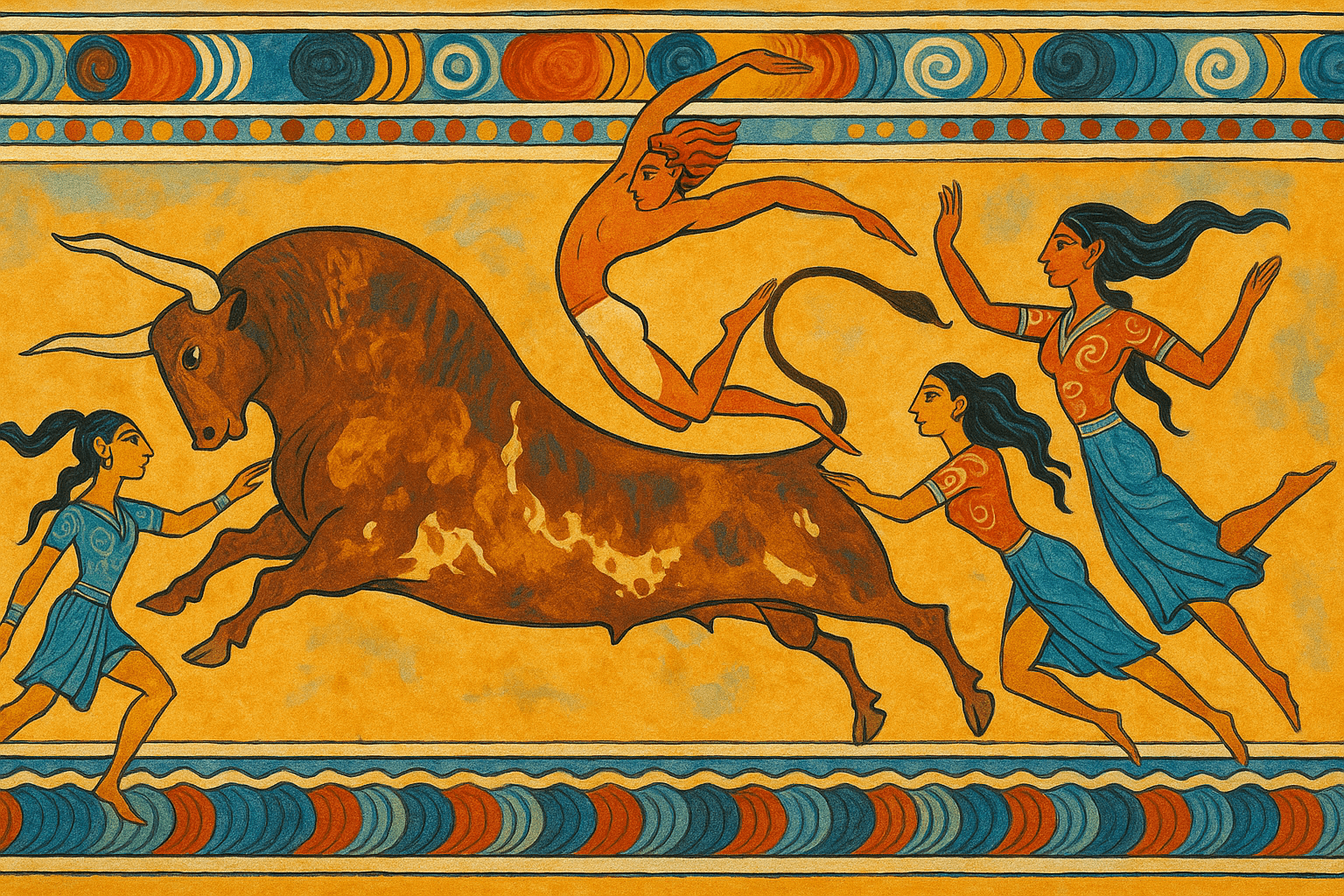

The most iconic depiction is the Bull-Leaping Fresco (or Toreador Fresco) discovered at the Palace of Knossos. It showcases a dynamic, three-part narrative within a single frame. On the left, a figure seizes the horns of a charging bull. In the center, another figure is captured mid-somersault, perfectly arched over the bull’s back. On the right, a third figure has just landed, arms raised as if to steady themselves.

One of the most debated aspects of this and similar scenes is the color of the figures. Following Egyptian artistic conventions of the time, Minoan artists often depicted male figures with reddish-brown skin and female figures with pale white skin. The Bull-Leaping Fresco features two white-skinned figures (the one preparing and the one landing) and one red-skinned figure (the leaper). This has led many to believe that both men and women participated in this perilous activity, perhaps as a team. This idea of gender inclusivity in such a high-stakes event makes the Minoans seem remarkably progressive for their time. These scenes are not isolated; the motif appears on seal stones, ivory figurines, and pottery, suggesting it was a central and recurring theme in Minoan culture.

The Mechanics of the Leap: A Dance with Death

The immediate question upon seeing these frescoes is: how was this even possible? The maneuver appears to defy physics and basic self-preservation. Archaeologists and acrobats have proposed several theories about the technique:

- The Evans Method: Sir Arthur Evans, the famed excavator of Knossos, believed the leaper would grab the horns of a charging bull, use the upward thrust of the animal’s head to launch into a backflip, and be caught by a partner behind the bull. This is the most dramatic interpretation but also the most dangerous and widely contested, as a bull’s neck-toss is violently unpredictable.

- The Frontal Leap: Another theory suggests the acrobat would run towards the bull from the front, place their hands on its back or shoulders as it dipped its head, and perform a forward handspring over its length.

- The Flank Leap: Perhaps the most plausible method involves the athlete approaching the bull from the side as it ran, jumping, placing their hands on its back, and vaulting sideways over the animal.

Some scholars argue the frescoes are not a literal, moment-by-moment depiction but a stylized, composite image showing the key stages of the event. Regardless of the exact technique, the skill, training, and sheer nerve required would have been extraordinary. This was not bullfighting in the Spanish sense, where the goal is to dominate and kill the animal. This was more of a fluid, acrobatic dance where the goal was to unite with the bull’s power and motion before escaping its wrath.

A Sacred Rite? The Religious Interpretation

So, why would anyone perform such a death-defying feat? The strongest theory points towards religion. The bull was an immensely powerful symbol in Minoan culture, representing virility, fertility, and raw natural power. The famous “Horns of Consecration,” stylized representations of bull horns, are found all over Minoan sacred sites. Exquisite bull-head rhytons—ceremonial vessels for pouring libations—further underscore the animal’s sacred status.

Viewed through this lens, bull-leaping transforms from a mere sport into a profound religious ceremony. The act of leaping over the sacred beast could have been a way of communing with a divine power or re-enacting a core mythological story that has been lost to time. By successfully navigating the raw power of the bull, the human leaper demonstrated a form of mastery or harmony with the natural world. The fact that these events likely took place in the central courts of the palaces—which were not just royal residences but also religious and administrative centers—strengthens the argument for their ceremonial significance.

A Sport, Spectacle, or Rite of Passage?

While deeply religious, the event was also surely a spectacle. The frescoes suggest an audience, and the pageantry would have captivated the Minoan populace. In this sense, it was an “extreme sport” for an elite class of highly trained athletes. Who these athletes were—captives, slaves, or youthful aristocrats—remains a mystery.

Another compelling theory combines the religious and sporting elements, framing bull-leaping as a coming-of-age ritual. In this interpretation, young Minoan men and women would have had to face the bull to prove their courage and transition into adulthood. The team dynamic seen in the frescoes—with a leaper, a “spotter”, and a preparer—could represent a group of initiates undergoing the trial together. Successfully completing the leap would be a public demonstration of their readiness to take on adult roles in society.

An Enduring Mystery

Ultimately, these theories are not mutually exclusive. The Minoan bull-leaping ritual was likely a complex event that was simultaneously a sacred rite, a thrilling spectacle, and a meaningful rite of passage. It was a multifaceted performance that lay at the very heart of Minoan identity.

Without written records to explain the rules, purpose, or outcomes, we are left to piece together the story from silent, vibrant images. The bull-leaper, forever suspended in mid-air on a palace wall, remains one of history’s most powerful symbols of daring and grace. It is a testament to the enigmatic spirit of the Minoans and their unique, dynamic relationship with the natural and the divine.