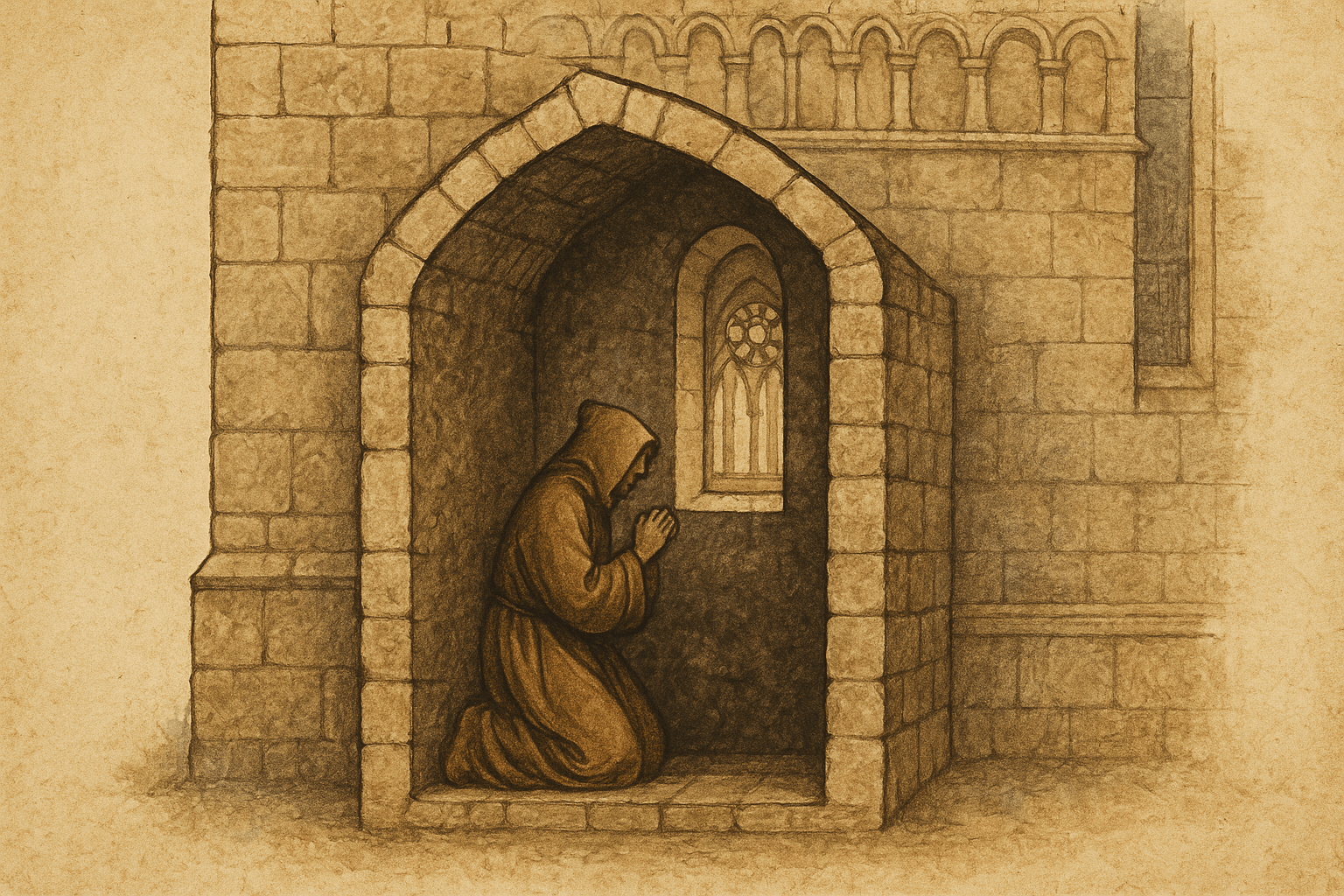

Imagine choosing to spend the rest of your life in a single, small room. Not as a punishment, but as a path to God. Imagine the door being sealed, not with a lock and key, but with stone and mortar, after a ceremony that more closely resembled a funeral than a new beginning. This was the reality for the medieval anchorite, one of history’s most radical and misunderstood spiritual figures.

Far from being forgotten hermits, these men (anchorites) and, more frequently, women (anchoresses) occupied a unique and surprisingly influential place in medieval society. Sealed within their “anchorholds”, they embraced a living death to the world, only to become the hidden, spiritual heart of their communities.

A Living Tomb, A Spiritual Womb

The defining feature of an anchorite was not just solitude, but permanent, immovable enclosure. While a hermit might wander the wilderness, an anchorite was literally “anchored” to their cell, which was typically built against the wall of a local church. The commitment was for life.

The process of becoming an anchorite was a profound public spectacle. The Rite of Enclosure was a solemn liturgical ceremony, presided over by a bishop. The prospective anchorite would lie before the altar as priests chanted the Office of the Dead over them—the very prayers said at a funeral. They were symbolically dying to the temporal world. After receiving Holy Communion for the last time as a free person, they were led to their cell. As the bishop blessed the enclosure, masons would begin to wall up the doorway, leaving the anchorite sealed inside until their actual death.

This cell was both a tomb, representing their separation from earthly life, and a womb, from which they would eventually be reborn into eternal life. It was the ultimate act of renunciation in pursuit of spiritual purity.

Life in the Anchorhold

What was life like inside this stone sanctum? The anchorhold was spartan, often consisting of just one or two small rooms. Its architecture was designed for a life balanced between total isolation and specific, controlled connection.

- The “Squint”: This was the anchorite’s most sacred connection. It was a small, narrow window, often covered by a grate, that looked directly into the church sanctuary. Through this opening, the anchorite could hear Mass, watch the consecration of the Eucharist, and receive communion. It was their lifeline to the sacraments.

- The Parlour Window: A second window faced outwards, towards the churchyard or a public lane. Covered by a shutter and a black cloth, this was the anchorite’s sole point of contact with the outside world. This is where their surprising role as a community advisor came into play.

- The Servant’s Hatch: A third, smaller opening was used by a servant who would deliver food, remove waste, and attend to the anchorite’s basic needs without direct contact.

Furnishings were minimal: a simple bed (sometimes just a stone slab), an altar with a crucifix, and perhaps a few devotional books. The goal was to eliminate all worldly distractions.

The Rhythm of Prayer and Contemplation

An anchorite’s day was a highly structured cycle of prayer, work, and contemplation. Their primary duty was to pray for the souls of their benefactors, the community, and all of Christendom. This routine was governed by the Liturgy of the Hours—the eight canonical hours of prayer recited daily by monks and nuns, from Matins in the dead of night to Compline before sleep.

To ward off the sin of idleness, many engaged in simple manual labor like mending clothes, creating lace, or transcribing manuscripts. The famous 13th-century guide for anchoresses, the Ancrene Wisse (Anchoresses’ Rule), advises its readers to keep their hands busy so their minds could remain focused on God. It warns, “An anchorite has no business but one: to tend to her soul.”

The Hidden Heart of the Community

Despite being physically walled off, anchorites were far from irrelevant. In fact, their extreme withdrawal made them powerful figures. They were seen as “spiritual athletes”—holy men and women whose constant prayer generated a protective aura around the entire community. People believed their presence brought God’s favor and warded off evil.

It was through the parlour window that this influence was most directly felt. Villagers, nobles, and clergy alike would come seeking counsel. They would confess their anxieties, ask for prayers for a sick child, or seek guidance on a difficult moral decision. The anchorite, detached from worldly temptations like greed or ambition, was considered an impartial and divinely inspired advisor.

The most famous example is Julian of Norwich, a 14th-century anchoress who lived in a cell attached to St. Julian’s Church in Norwich, England. From her anchorhold, she experienced a series of profound divine visions. She didn’t keep them to herself; she wrote them down in a book now known as Revelations of Divine Love, the earliest surviving book in English written by a woman. People, including the famous mystic Margery Kempe, traveled to her window to seek her wisdom. Julian’s life demonstrates the paradox of the anchorite: physically confined, she became one of the most influential theologians of her time.

Why Embrace the Wall?

What could motivate someone to choose such an extreme existence? The primary driver was, without question, an intense and all-consuming love for God and a desire for a life of uninterrupted prayer. In a world full of plague, war, and uncertainty, the anchorhold offered a direct, if difficult, path towards salvation.

For women, the anchoritic life also offered a unique form of agency and spiritual authority. It was an alternative to arranged marriage and childbearing, but it was also distinct from life in a convent, which was often hierarchical and socially structured. As an anchoress, a woman could become a respected spiritual master on her own terms, occupying a role that few other medieval women could ever hope to attain.

The medieval anchorite represents a form of devotion that is almost impossible for the modern mind to comprehend. Yet, in their stone cells, these individuals found a radical kind of freedom. By dying to the world, they discovered a universe within and became unwavering beacons of faith for the world they had left behind.