Forging Order from Chaos

The architect of this new era was Tokugawa Ieyasu, a patient, cunning, and ultimately triumphant daimyō. After the climactic Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, where he defeated a coalition of his rivals, Ieyasu consolidated his power. In 1603, he had the Emperor appoint him shōgun—the supreme military dictator of Japan. He established his government in the small fishing village of Edo, which would grow into the modern metropolis of Tokyo.

Unlike his predecessors who sought only to conquer, Ieyasu’s primary goal was to create a system so stable it would prevent future wars and secure his family’s rule for generations. The Tokugawa regime was built on one central principle: control. Every policy was designed to suppress potential threats and lock society into a predictable, manageable hierarchy.

The Art of Control: Taming the Warlords

The greatest threat to the shogunate came from the daimyō, the very warlords who had once been Ieyasu’s peers. To defang these powerful figures, the Tokugawa implemented a stroke of political genius known as sankin-kōtai, or “alternate attendance.”

This system required every daimyō to:

- Maintain a lavish residence in the capital city of Edo and live there for a full year, alternating with a year in their home domain.

- Leave their wife and heir in Edo permanently as political hostages.

The effects of sankin-kōtai were profound. Firstly, it was a massive financial drain. The cost of maintaining two luxurious households and funding the semi-annual procession to and from Edo crippled the daimyō’s finances, leaving them with little money to raise armies or plot rebellion. Secondly, it placed them under the shogun’s constant surveillance and forced them to spend a significant part of their lives participating in the political life of the capital. Any hint of disloyalty could mean disaster for the family members left behind in Edo. The policy effectively turned potential rivals into courtiers.

A Society in its Place: The Four-Tier System

To ensure stability at every level, the Tokugawa government enforced a rigid, neo-Confucian social hierarchy known as the shinōkōshō. Society was divided into four distinct classes, with no mobility between them:

- Samurai (Shi): At the top were the warriors. With no wars to fight, their role transformed. They became a ruling class of bureaucrats, administrators, and scholars, their swords becoming more of a symbol of status than a tool of war.

- Peasants (Nō): The farmers were considered the foundation of the nation, as they produced the rice that was the basis of the economy. They were honored in theory but often lived harsh lives under a heavy tax burden.

- Artisans (Kō): The craftsmen who produced the goods, tools, and art for society.

- Merchants (Shō): At the bottom of the official hierarchy were the merchants. Seen as unproductive parasites who profited from the labor of others, they were officially disdained.

This system was designed to eliminate the kind of social climbing and ambition that had fueled the chaos of the Sengoku period. Everyone had a clearly defined place and function, creating a society that was predictable and, above all, stable.

Closing the Gates: The Sakoku Policy

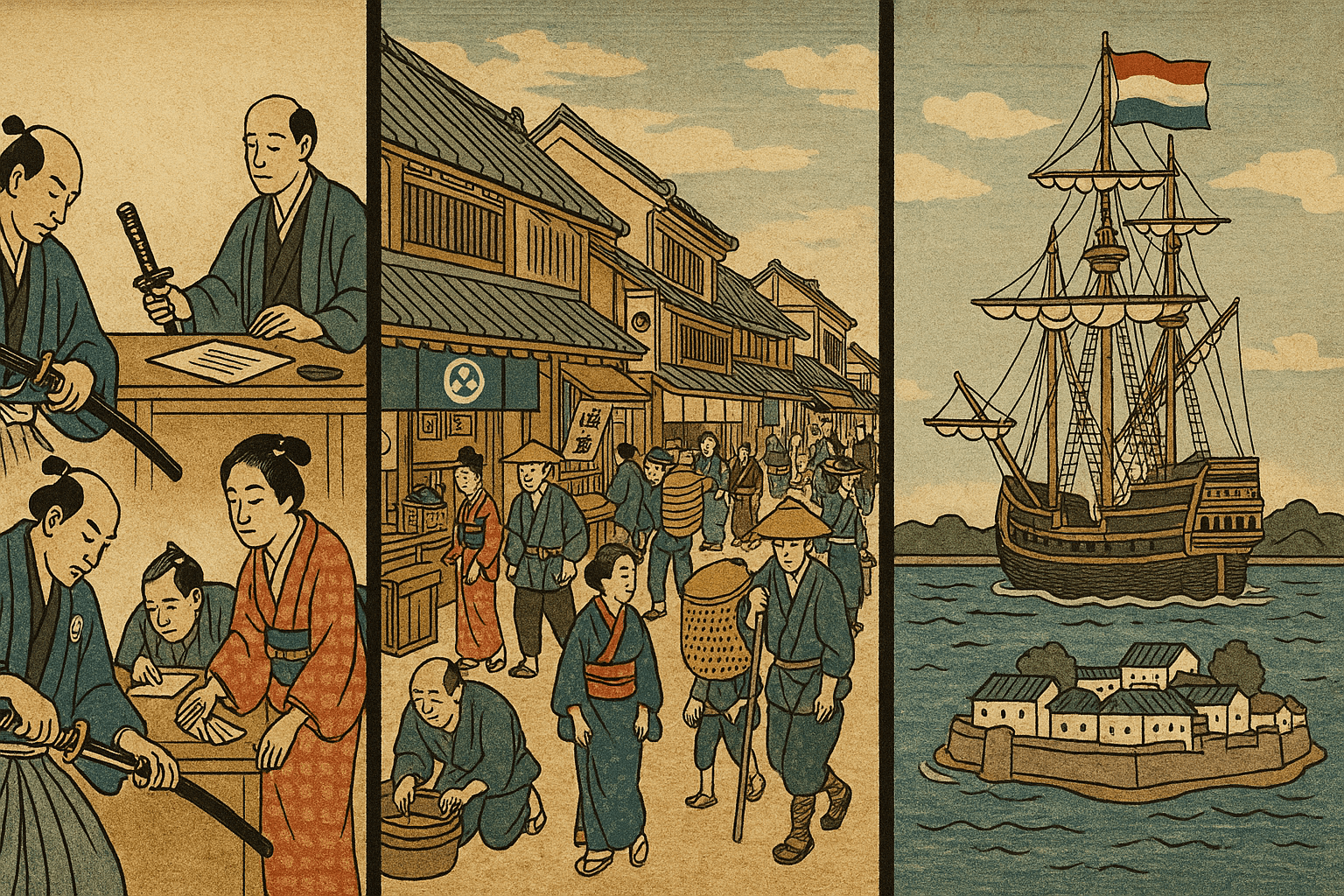

The final pillar of Tokugawa control was the policy of national seclusion, or sakoku (“chained country”). In the 1630s, the shogunate issued a series of edicts that radically restricted Japan’s interaction with the outside world. The primary motivation was fear—fear of the destabilizing influence of European colonialism and Christianity, which demanded loyalty to a foreign pope over the shogun.

The sakoku edicts forbade Japanese from leaving the country on pain of death, banned most foreign traders, and prohibited the construction of large, ocean-worthy ships. Trade and contact were funneled through a single, tiny, fan-shaped artificial island in Nagasaki harbor called Dejima. Only the Dutch and Chinese were permitted to trade there, and only under incredibly strict observation. Through the Dutch, a trickle of Western scientific, medical, and technological knowledge—known as Rangaku or “Dutch Learning”—flowed into Japan, ensuring the country was not completely ignorant of global developments.

The Floating World: A Culture of Peace

Ironically, this highly restrictive system fostered an explosion of cultural creativity. With the samurai pacified, the daimyō impoverished, and the country at peace, a new cultural force emerged: the merchant class. Though officially at the bottom of the social ladder, merchants accumulated immense wealth and began to spend it on entertainment and luxury.

This gave rise to the culture of the ukiyō, or the “Floating World”—the vibrant, hedonistic world of the urban pleasure districts. In the bustling cities of Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto, an incredible new culture flourished:

- Art: Ukiyo-e woodblock prints became a popular art form, depicting scenes from the Floating World, beautiful courtesans, famous kabuki actors, and landscapes. Artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige created iconic images, like “The Great Wave off Kanagawa”, that were affordable to the common person.

- Theatre: Lavish and dramatic Kabuki theatre, with its elaborate costumes and makeup, told stories of romance, conflict, and historical legend. Intricate Bunraku puppet theatre also drew huge crowds.

- Literature: The haiku was perfected as a poetic form by masters like Matsuo Bashō, and popular novels captured the adventures and romances of city life.

The Long Peace was a profound trade-off. Individual freedoms and international engagement were sacrificed for collective security and internal stability. For over two and a half centuries, the system worked. The Tokugawa created a peaceful, highly literate, and economically integrated nation. And when Commodore Perry’s “Black Ships” arrived in 1853 to force Japan open, it was this uniquely developed and unified nation that was able to meet the challenge, rapidly transforming itself from a secluded feudal society into a modern industrial power.