Imagine setting sail in a hand-carved canoe, navigating treacherous coral reefs and the unpredictable currents of the South Pacific. Your journey will last for weeks and cover hundreds of miles. Your goal isn’t to conquer, nor is it to trade for food or tools. Your singular purpose is to give away a precious shell necklace, and in return, receive an equally precious shell armband. To a Western eye, this might seem like madness. But for the people of the Massim Archipelago, east of New Guinea, this was the heart of one of the most sophisticated and fascinating social systems ever documented: the Kula Ring.

What Exactly is the Kula Ring?

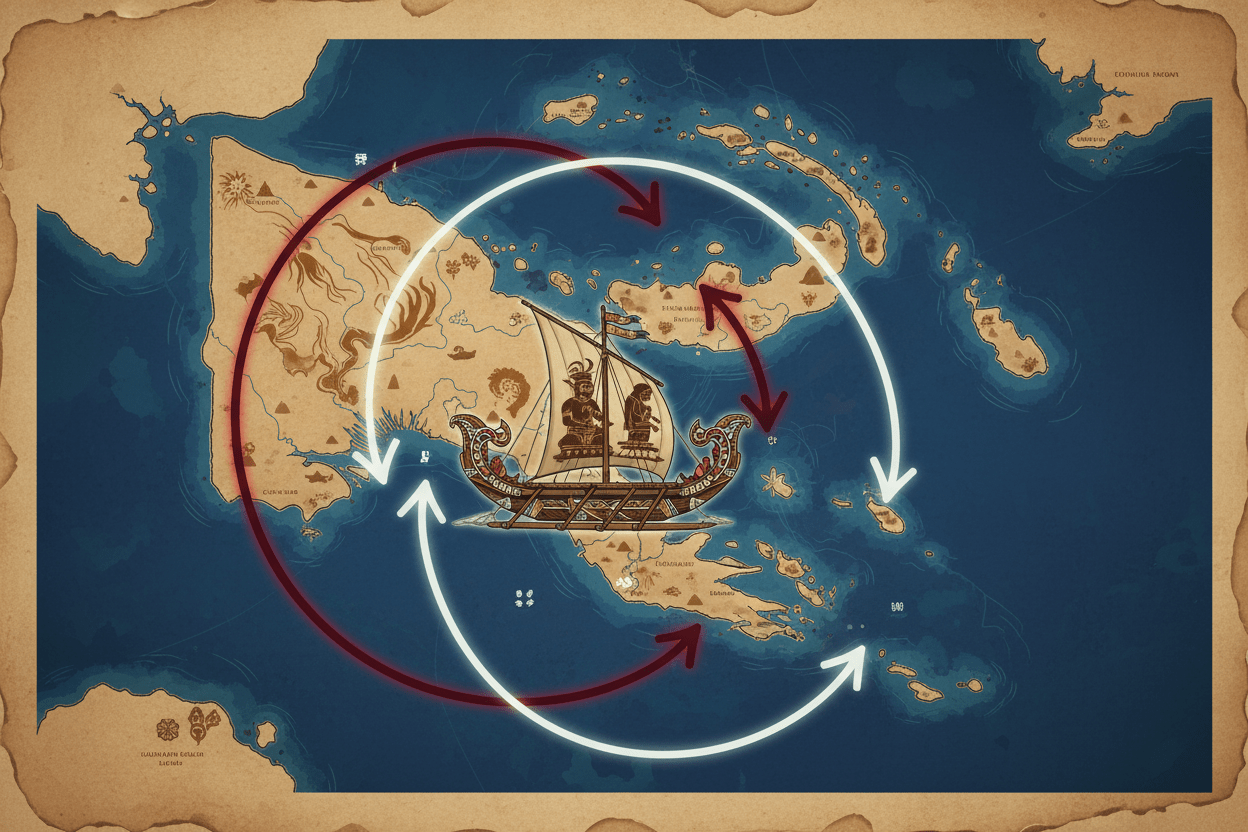

At its most basic level, the Kula Ring is a vast, inter-island ceremonial exchange system, most famously practiced by the Trobriand Islanders. It is a closed circuit, connecting eighteen island communities in a loop that spans hundreds of miles. The exchange involves two specific types of ceremonial valuables, or vaygu’a:

- Soulava: Long necklaces made of red spondylus shell discs. These precious items always travel clockwise around the ring of islands.

- Mwali: Bracelets or armbands carved from the white conus shell, often decorated with other shells and beads. These always travel counter-clockwise.

A man who receives a soulava necklace from a partner on a neighboring island is obligated, in time, to give a mwali armband of equivalent value in return. The items themselves are never static. They are constantly in motion, flowing in opposite directions around the archipelago. The aim is not to accumulate a hoard of both necklaces and armbands; the goal is to have your name associated with the flow. The most powerful men are those who can successfully transact the most valuable and famous pieces.

Crucially, these are not commodities. They are not money. They have no practical use and are rarely even worn, except on the most important ceremonial occasions. Their value lies in their history. Like a famous painting or a historic jewel, each major Kula valuable has a name, a story, and a list of its previous owners. To possess one, even temporarily, brings immense prestige.

Gifts as Power: The Social Fabric of Kula

The brilliance of the Kula Ring is that it was never about the objects themselves; it was about the relationships they created. This wasn’t “trade” in the modern sense, but a system of “total social fact”, as sociologists would call it, weaving together politics, kinship, and economics.

The act of giving a Kula valuable created a powerful social bond and an obligation. This relationship, known as keda, was a lifelong partnership between men on different islands. Your Kula partner was your ally, your protector, and your host in a foreign land. When you traveled to his island, he was bound by honor to provide you with safety, food, and shelter.

This network of alliances was the true currency of the Kula. In a region historically marked by intermittent warfare and suspicion between island groups, the Kula created a web of peace and interdependence. It provided a safe framework for other, more practical forms of trade (known as gimwali) to occur. While the Kula partners ceremonially exchanged their shells, their followers might be bartering for essential goods like pottery, yams, pigs, or canoe timber on the side. The Kula was the high-status, sacred transaction that enabled the profane, everyday trade to happen safely.

A man’s reputation was built on his Kula performance. Generosity was paramount. To be a slow, reluctant, or stingy giver was to invite scorn. A great man was one who had many Kula partners and through whose hands the most storied necklaces and armbands passed. In this system, power and influence were demonstrated not by what you owned, but by what you were able to give away.

The Epic Voyage and the Role of Magic

Participating in the Kula was a monumental undertaking. It involved organizing large expeditions, building magnificent, 60-foot ocean-going canoes called waga, and recruiting a crew for the dangerous voyage. These canoes were works of art, adorned with intricate carvings and paintwork designed to dazzle their exchange partners.

Magic was woven into every single aspect of the Kula. It wasn’t just a physical journey but a spiritual one. Magical rites were performed to:

- Protect the canoe builders and make the vessel swift and safe.

- Calm the winds and seas for the voyage.

- Make the travelers aesthetically beautiful and impressive in the eyes of their partners.

- Most importantly, to “cloud the mind” of their Kula partner, making them generous and willing to part with their most prized valuable.

This deep integration of magic underscores that the Kula was far more than an economic system. It was a sacred ritual that affirmed their worldview, their connection to their ancestors, and their power over the natural and social worlds.

Malinowski and a Revolution in Thought

The Western world owes its understanding of the Kula Ring almost entirely to one man: the Polish-born anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski. Stranded in the Trobriand Islands during World War I due to his Austrian citizenship, Malinowski turned his predicament into an opportunity. Instead of observing from the Veranda like his predecessors, he lived among the islanders, learned their language, and participated in their daily lives—inventing the anthropological method of “participant observation.”

His 1922 masterpiece, Argonauts of the Western Pacific, meticulously documented the Kula Ring. The book was a bombshell in academic circles. It shattered the prevailing colonial-era assumption that “primitive” societies were driven by simple, rational needs. Malinowski showed the world a complex society motivated by status, honor, magic, and a sophisticated gift economy that defied Western economic logic. He forced the West to reconsider its definitions of wealth, value, and power.

The Enduring Legacy

The Kula Ring is still practiced today, though on a smaller scale. Motorboats have often replaced the majestic canoes, and the system now coexists with a cash economy. Yet its core principles endure. The Kula Ring remains a powerful historical testament to human ingenuity. It demonstrates that societies can build vast, stable networks of cooperation and trust based on generosity and obligation rather than pure material profit. In a world often defined by cold, impersonal transactions, the story of the Kula is a vital reminder that for millennia, gifts have been a profound source of power, binding people together across the vast and dangerous seas.