What Was Scrofula, the “King’s Evil”?

The disease at the heart of this ritual was scrofula, a condition known grimly as the morbus regius, or the “King’s Evil.” We now know scrofula as a form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, where the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacterium infects the lymph nodes, particularly in the neck. Its symptoms were distressing and highly visible: large, painless swellings would appear on the neck, which could eventually rupture and drain, leaving behind prominent scars and open sores.

In a pre-scientific age, the chronic nature of the disease, its unsightly appearance, and its resistance to conventional treatments made it a source of great fear and social stigma. The belief that such a persistent affliction could only be vanquished by a king gave it its name and cemented its place in the popular imagination. The “King’s Evil” needed a king’s cure.

The Divine Right to Heal: Origins of a Sacred Tradition

The practice of the Royal Touch emerged from the medieval concept of the Divine Right of Kings. This doctrine held that a monarch was God’s chosen representative on Earth, imbued with a sacred quality or divine grace (virtus). This sacredness wasn’t just symbolic; it was believed to manifest in tangible ways, including the power to perform miracles.

The tradition has two distinct origins:

- In France: The practice is most often traced back to Robert II “the Pious” (reigned 996–1031). French kings were said to inherit this healing ability through their spiritual connection to Saint-Marcoul, and the ritual was an important part of their sacral kingship, reaffirmed at their coronation.

- In England: The tradition began with the deeply religious Anglo-Saxon king, Edward the Confessor (reigned 1042–1066). His reputation for piety was so great that he was canonized a century after his death. Norman and Plantagenet successors eagerly adopted the practice, as it was a powerful way to legitimize their rule and visually demonstrate their divine mandate, connecting them to the beloved saint-king.

For a king, performing the touch was not merely an act of charity. It was a potent political statement—a recurring public performance that reinforced their legitimacy and God-given authority over their subjects.

The Ceremony: Political Theater and Pious Ritual

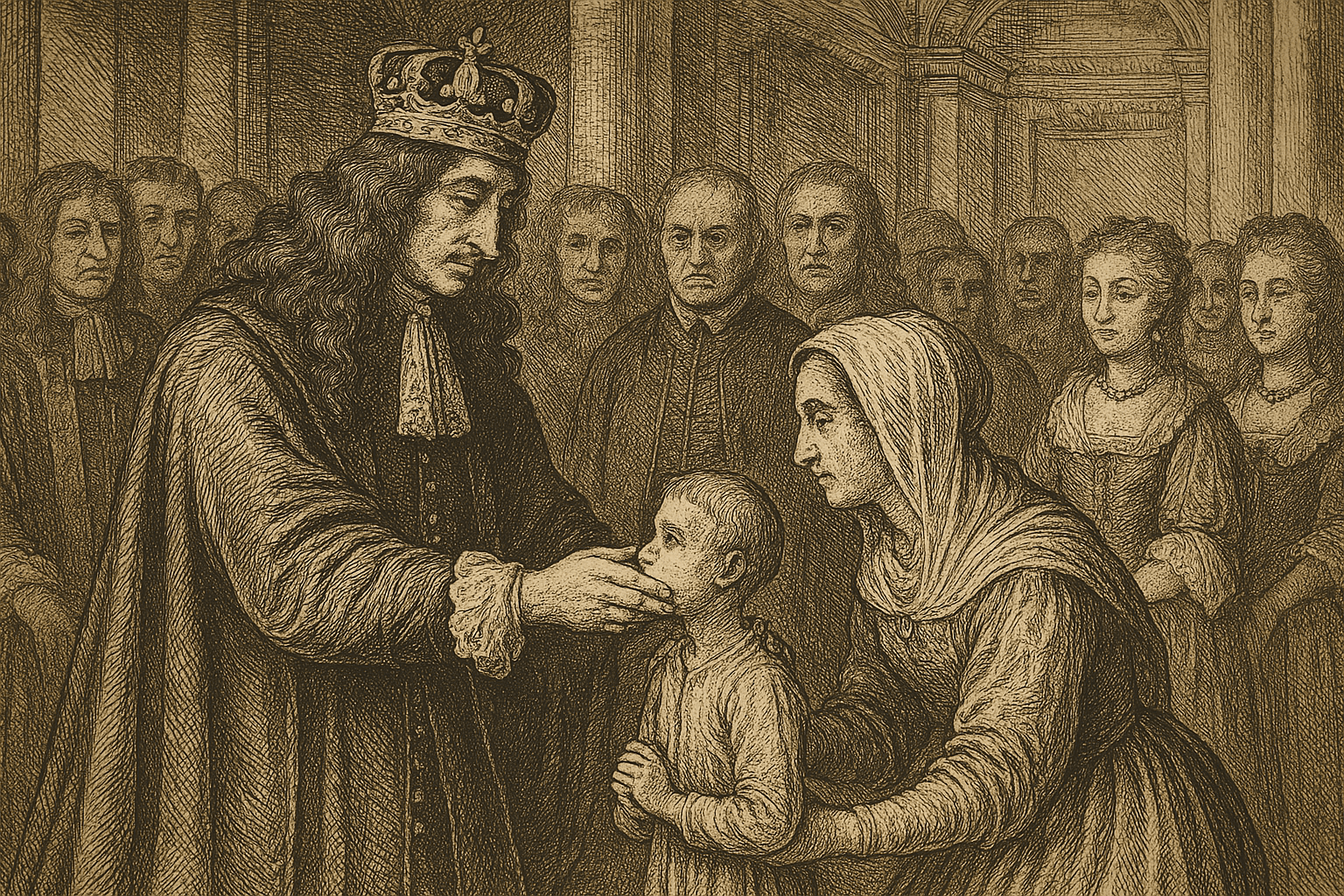

The touching ceremony was a highly orchestrated event, far from a spontaneous act of healing. While the specifics varied over time and between kingdoms, the core elements remained consistent, creating a spectacle of profound social importance.

First, a potential patient couldn’t simply line up at the palace gates. They typically needed a certificate from their parish priest or a surgeon, verifying that they genuinely suffered from scrofula and had not been touched by the monarch before. This vetting process controlled numbers and added a layer of officialdom to the proceedings.

The event itself often took place on religious feast days in a grand hall or royal chapel. The ceremony would begin with prayers and readings from the Gospels, frequently citing Mark 16:18: “They shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.” Then, the monarch would proceed down a line of kneeling sufferers. With great solemnity, the king or queen would touch the afflicted area—the swollen neck, the sores on the face—while a chaplain recited, “He touched them, and he healed them.”

The ‘Touch-Piece’

After the touch, each person was given a special coin, known as a ‘touch-piece.’ In England, this was often a gold Angel coin, which depicted the Archangel Michael slaying a dragon. This coin was pierced and hung around the recipient’s neck on a ribbon. It was not payment but a critical part of the cure—an amulet to be worn continuously to prevent the disease from returning. Losing the coin was considered a grave misfortune that could cause a relapse.

Some monarchs embraced the ritual with extraordinary vigor. France’s Louis XIV, the “Sun King”, touched around 2,000 people on Easter Sunday in 1680 alone. In England, after the monarchy was restored, Charles II used the ceremony as a magnificent piece of public relations. Having defeated the republicans who executed his father, Charles II’s revival of the touch was a clear message: the true, divinely appointed king was back. He is estimated to have touched nearly 100,000 people during his 25-year reign. The famous diarist Samuel Pepys recorded the “strangeness” of the sight, watching the king “stroaking the people’s faces with his hands.”

Skepticism and the End of an Era

So, did it work? From a modern medical perspective, the answer is no. Scrofula, like other forms of tuberculosis, can sometimes go into spontaneous remission. Many of the “cures” were likely due to this, misdiagnosis, or the powerful psychological impact of the placebo effect. Believing so fervently in the monarch’s divine power, and wearing a golden amulet as a constant reminder, could have had a profound-if temporary-psychosomatic effect on a sufferer’s well-being.

The decline of the practice was driven by the seismic shifts of the Enlightenment. As rationalism and scientific inquiry gained ground, belief in miracles and the divine right of kings began to wane.

In England, the Protestant ruler William III was deeply skeptical. Faced with a crowd of sufferers, he is said to have dismissed them with the words, “God give you better health and more sense.” The last British monarch to perform the ceremony was Queen Anne. One of the last children she touched, in 1712, was a young Samuel Johnson, who would grow up to be one of England’s greatest literary figures (the touch did not cure him).

In France, the ritual persisted until it was swept away by the French Revolution of 1789, which utterly destroyed the concept of sacred monarchy. Though King Charles X attempted to revive it at his coronation in 1825, the gesture was widely mocked as an absurd throwback to a bygone age.

The story of the King’s Touch for scrofula remains a captivating window into the pre-modern world. It reveals a time when the health of the body was inseparable from the health of the body politic, and the touch of a king was seen as a direct conduit to the divine—a magical, medicinal, and masterful display of power.