Imagine a battlefield in the heart of 15th-century Europe. On one side, the flower of Christendom’s chivalry: thousands of German, Hungarian, and Italian knights, clad in shining plate armor and mounted on powerful warhorses. They are the epitome of medieval military might. On the other side, a determined mass of Bohemian peasants, artisans, and minor nobles. They have no grand cavalry charge to offer. Instead, they have faith, fury, and a revolutionary invention: the war wagon.

For nearly twenty years, these proto-protestant rebels would use their mobile fortresses to defy the combined power of the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, changing the art of war forever. This is the story of the Hussite Wars and the incredible Wagenburg.

The Spark: A Reformer’s Fiery End

The conflict didn’t begin on the battlefield, but in the lecture halls and pulpits of Prague. Jan Hus, a charismatic preacher and rector of Charles University, was a voice of reform in a time of deep corruption within the Catholic Church. Inspired by the English reformer John Wycliffe, Hus condemned the sale of indulgences, criticized the immense wealth and worldly power of the clergy, and argued that the laity should receive communion “in both kinds” (both bread and wine), a practice then reserved for priests.

His teachings resonated deeply with the Czech people, tapping into a growing sense of national identity and resentment against ecclesiastical abuses. In 1414, Hus was summoned to the Council of Constance to defend his ideas, traveling under a promise of safe conduct from the Holy Roman Emperor, Sigismund. It was a trap. Hus was arrested, tried for heresy, and, after refusing to recant his beliefs, burned at the stake on July 6, 1415.

When news of his martyrdom reached Bohemia, it lit a powder keg of outrage. The execution of their beloved reformer was seen as an act of ultimate betrayal. Hussite nobles formed a league to protect freedom of preaching, and radical sentiments boiled over. In 1419, a Hussite procession in Prague turned violent, culminating in the “First Defenestration of Prague”, where Hussite radicals threw the town’s Catholic councillors from the windows of the New Town Hall. The revolution had begun.

Necessity, the Mother of Military Invention

Emperor Sigismund, the same man who had guaranteed Hus’s safety, inherited the Bohemian throne shortly after. In response to the rebellion, the Pope declared a crusade against the heretical Czechs. The Hussites were now enemies of the Holy Roman Empire and the entire Catholic world. They were vastly outnumbered and faced armies of professional, heavily armored knights.

The Hussites, led by brilliant commanders like the one-eyed general Jan Žižka, knew they could not win a conventional battle. They couldn’t match the crusaders’ cavalry charge for charge. They needed an equalizer, a way to neutralize the knight’s greatest advantage. They found it in an object common to every village and farm: the wagon.

The Wagenburg: A Fortress on Wheels

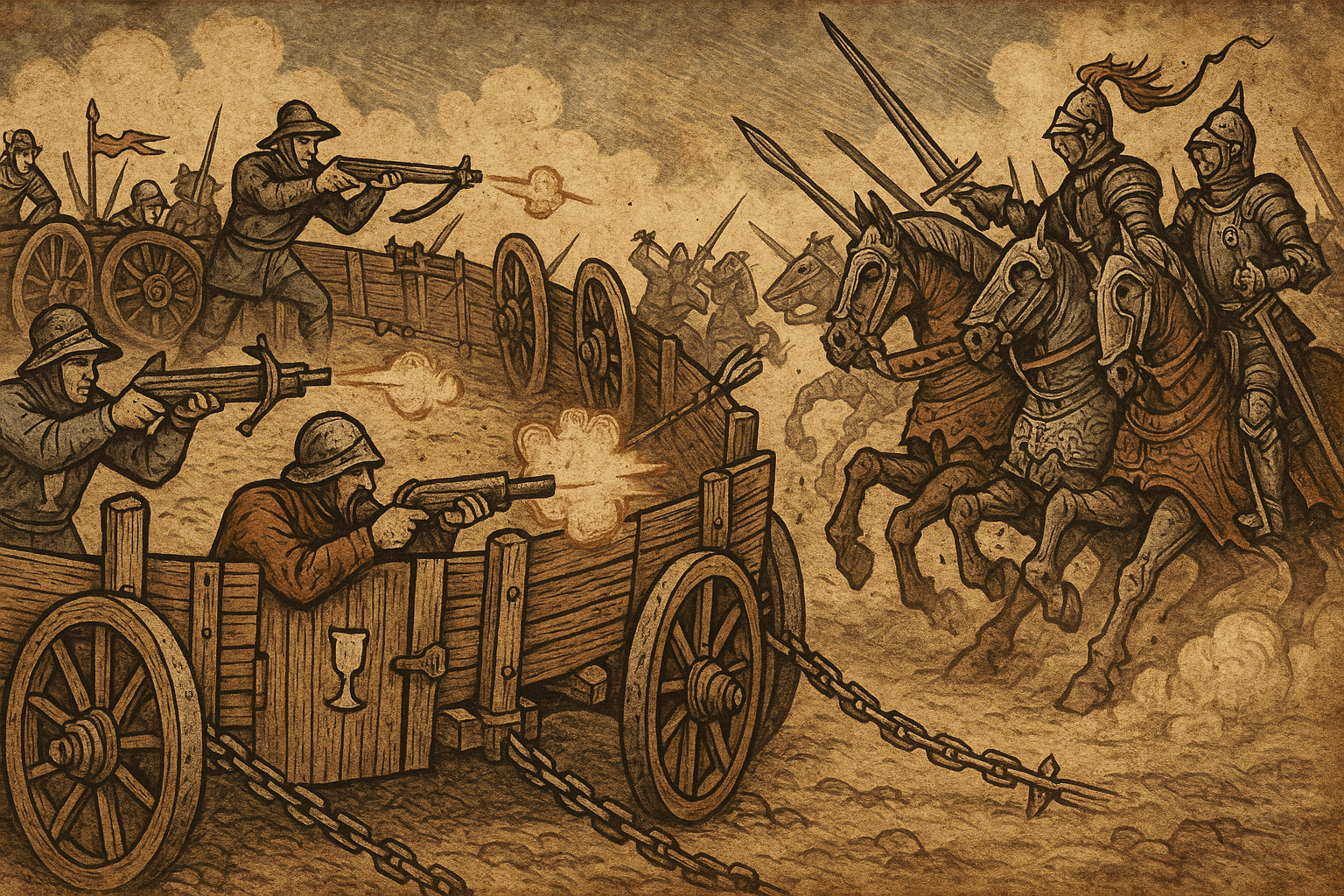

The Hussite war wagon, or vozová hradba (wagon wall), was far more than a simple farm cart. It was a purpose-built implement of war, a medieval infantry fighting vehicle. These wagons were ingeniously designed for both defense and offense.

- Fortification: The sides were reinforced with thick hardwood planks, creating a protective wall against arrows and lances. Small slits were cut into the planks for crossbowmen and early handgunners to fire through.

- Crew: Each wagon carried a crew of 16-22 soldiers. This mixed force typically included crossbowmen, handgunners with primitive firearms called píšťala (hand cannons), men armed with long, spiked peasant flails, and pikemen to repel boarders.

- Interlocking Design: The wagons were designed to be chained together, wheel to wheel, forming an impenetrable circular or square fortress known as a Wagenburg (“wagon castle”). Gaps could be filled with large pavise shields, creating a solid defensive line.

The Tactics of the Wagon Castle

The genius of the Wagenburg lay in how it was deployed. Under Jan Žižka’s command, the Hussites would choose their ground carefully, often occupying a commanding hilltop. As the crusader army approached, the wagons would quickly form their defensive perimeter.

The battle followed a devastatingly effective pattern:

- The Charge: The overconfident crusader knights would launch a massive cavalry charge, expecting to smash through the peasant rabble.

- The Barrage: As they charged, they were met with a disciplined and terrifying storm of projectiles. Hussite light artillery, positioned in the center of the fort, would open fire. As the knights got closer, a hail of crossbow bolts and lead shot from the hand cannons would rip through their ranks, maiming horses and piercing armor.

- The Wall: The charge would inevitably lose momentum and break against the physical barrier of the chained wagons and the bristling pikes of the defenders. The knights would become a confused, panicked mass, their primary weapon—the coordinated charge—completely neutralized.

- The Counter-Attack: This was the masterstroke. Once the enemy was disorganized and demoralized, designated “gates” in the wagon line would swing open. Fresh Hussite infantry, wielding terrifying agricultural weapons like war flails, would pour out and fall upon the entangled and exhausted knights, turning the failed attack into a bloody rout.

The Blind General and Decades of Victory

Jan Žižka, a hardened veteran who lost one eye in a previous war and the other during the Siege of Rabi in 1421, was the mind behind this tactical revolution. Even when completely blind, he continued to lead the Hussite armies, directing battles from a command wagon by having the battlefield described to him in detail. His strict military code and tactical brilliance forged a disparate group of rebels into one of Europe’s most effective fighting forces.

Between 1420 and 1431, five separate crusades were launched against the Hussites, and every single one was defeated. Battles like Vítkov Hill (1420), Kutná Hora (1421), and Aussig (1426) became legendary examples of how the Wagenburg could decimate a numerically superior and better-equipped foe.

The Legacy of the War Wagon

The Hussite Wars eventually wound down due to internal divisions between the radical Taborites and the more moderate Utraquists, culminating in the Battle of Lipany (1434) where Hussites fought Hussites. A compromise was eventually reached with the Church in the Compacts of Basel.

However, the military legacy of the war wagon was profound. It proved that disciplined, well-led infantry armed with gunpowder weapons and innovative tactics could defeat the feudal knight. It was a key moment in the “Infantry Revolution” that would redefine European battlefields in the coming centuries.

The story of the Hussites and their Wagenburg is a powerful testament to human ingenuity in the face of overwhelming odds. It shows how faith, combined with revolutionary thinking, allowed a small nation to stand against the world and, in doing so, help bring the age of the knight to a fiery, gunpowder-fueled end.