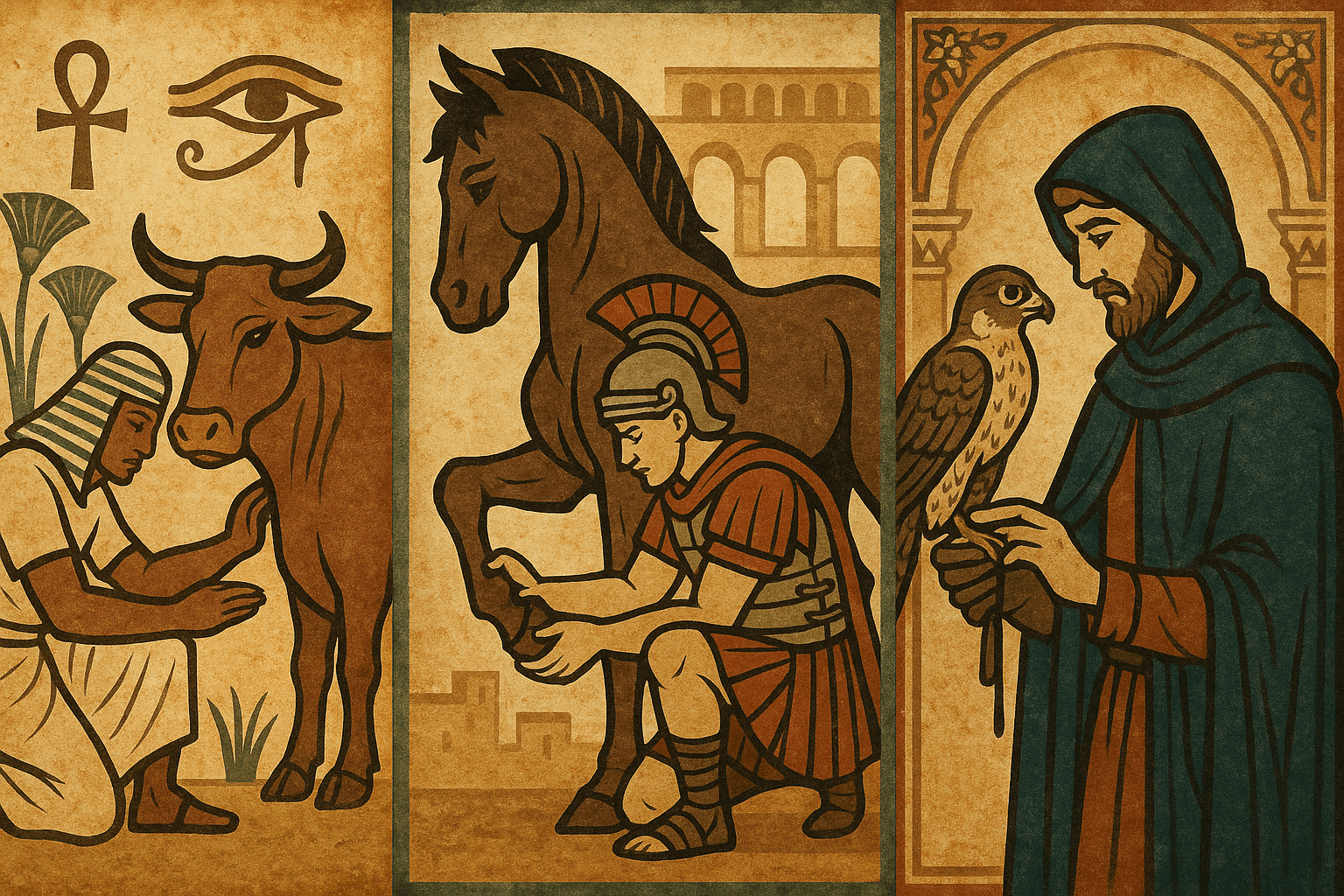

From Husbandry to Healing: The Earliest Care

The story begins not with medicine, but with value. The Neolithic Revolution, roughly 12,000 years ago, saw humans domesticate animals like goats, sheep, cattle, and pigs. This monumental shift turned wild creatures into living assets. A sick ox could mean an unplowed field and a failed harvest. A diseased flock could spell starvation for a village. At this point, “veterinary care” was a matter of pure pragmatism, a blend of practical experience, herbal remedies, and a heavy dose of superstition. A shepherd who learned which plants soothed an animal’s stomach ailment or how to set a simple fracture was a vital member of the community.

The first written evidence of this specialized care comes from ancient Mesopotamia. The Code of Hammurabi, dating to around 1754 BCE, includes laws that stipulate the fees for “doctors of oxen and asses” and the penalties for malpractice. This tells us two crucial things: animal healing was already a recognized profession, and it was regulated because of the economic importance of the animals.

Glimmers of Science in the Ancient World

As empires rose, so did the systematization of knowledge. In Egypt, the Kahun Papyrus (c. 1800 BCE) contains sections on veterinary medicine, discussing diseases in cattle, dogs, birds, and fish. Given their reverence for animals and sophisticated medical practices for humans, it’s no surprise they extended this observation to the creatures around them.

However, it was in ancient India where veterinary science truly flourished into a distinct discipline. The cornerstone text is the legendary Shalihotra Samhita, an encyclopedia on equine medicine attributed to the sage Shalihotra (c. 2350 BCE). This vast treatise described horse anatomy, physiology, surgery, and treatments for over 70 diseases. Shalihotra is often considered the father of veterinary science.

Care wasn’t just for horses. As elephants were vital for warfare, labor, and ceremony, their health was paramount. Texts like the Hastyayurveda (Ayurveda of Elephants) offered detailed guidance on everything from surgery and toxicology to diet and behavior, demonstrating a remarkably sophisticated level of specialized knowledge.

Rome’s Military Medics

The Romans, ever the pragmatists, professionalized animal care out of military and economic necessity. The vast Roman legions were powered by horses and mules, and the empire’s supply lines depended on oxen. A breakdown in this “animal machinery” could halt an army. To keep their forces moving, the Romans established the role of the veterinarius. Initially meaning “one who deals with beasts of burden” (veterinae), these individuals were often skilled soldiers or slaves attached to the cavalry units. They were responsible for treating wounds, managing lameness, and ensuring the health of the animals that were as crucial as any legionary. Writers like Columella, in his work De Re Rustica (On Agriculture), dedicated entire volumes to the care and diseases of farm animals, compiling the best practices of the day.

The Middle Ages: A Tale of Horses and Hawks

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, much of this classical knowledge was lost or fragmented. Veterinary care reverted largely to folk traditions and the hands of the local farrier—a term derived from the Latin ferrum (iron), highlighting the close link between horseshoeing and general horse care.

Yet, two animals commanded special attention from the elite: the warhorse and the falcon. The knight’s destrier was a priceless military asset, a medieval tank whose health was of strategic importance. Manuals on horsemanship and care became common, ensuring these valuable animals were kept in peak condition.

Even more specialized was the care afforded to birds of prey. Falconry was the sport of kings and nobles, and a trained falcon was a status symbol. This led to remarkably detailed treatises on avian medicine. The most famous is De Arte Venandi cum Avibus (The Art of Hunting with Birds), written by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the 13th century. It contained meticulous observations on avian anatomy, the molting process, and specific treatments for diseases—a bright spot of empirical science in an age often defined by dogma.

The Dawn of the Modern Profession

The Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution rekindled an interest in anatomy and empirical observation. Carlo Ruini’s 1598 book, Anatomia del Cavallo (Anatomy of the Horse), was a landmark achievement. With its detailed woodcut illustrations, it was the first comprehensive anatomical treatise on a non-human species, doing for the horse what Vesalius had done for the human body.

But the true birth of the modern veterinary profession was forged in crisis. Throughout the 18th century, devastating epizootics—animal plagues—swept across Europe. Rinderpest, a viral disease affecting cattle, wiped out hundreds of thousands of animals, crippling national economies. Governments realized that folk remedies and farriers were no match for such a threat. A scientific approach was desperately needed.

In response, French riding master Claude Bourgelat was authorized by King Louis XV to found the world’s first veterinary school in Lyon, France, in 1761. Its primary mission was to study and combat Rinderpest. Bourgelat’s approach was revolutionary: he insisted that the study of animal anatomy, physiology, and pathology was the essential foundation for treating disease. The success of the Lyon school spurred the creation of similar institutions across Europe, from London to Berlin. Veterinary medicine was finally established as a learned and scientific profession.

The journey from an ancient shepherd applying a poultice to a modern surgeon performing a complex operation is a long and storied one. The history of veterinary medicine is a testament to our enduring reliance on animals and our growing capacity for empathy and scientific understanding. Every veterinarian today stands on the shoulders of millennia of observation, from the Indian sage caring for his elephants to the Roman soldier tending his horse, all part of the timeless effort to heal the creatures who share our world.