The eye, often called the “window to the soul”, holds a unique place in human culture and connection. Its loss, whether through injury or disease, has been a profound challenge throughout history. Yet, for almost as long as humans have faced this loss, they have sought to remedy it. This is the surprisingly long and complex history of the ocular prosthetic—a story of medicine, artistry, and the deep-seated human desire for wholeness.

More Symbolic Than Functional: Ancient Beginnings

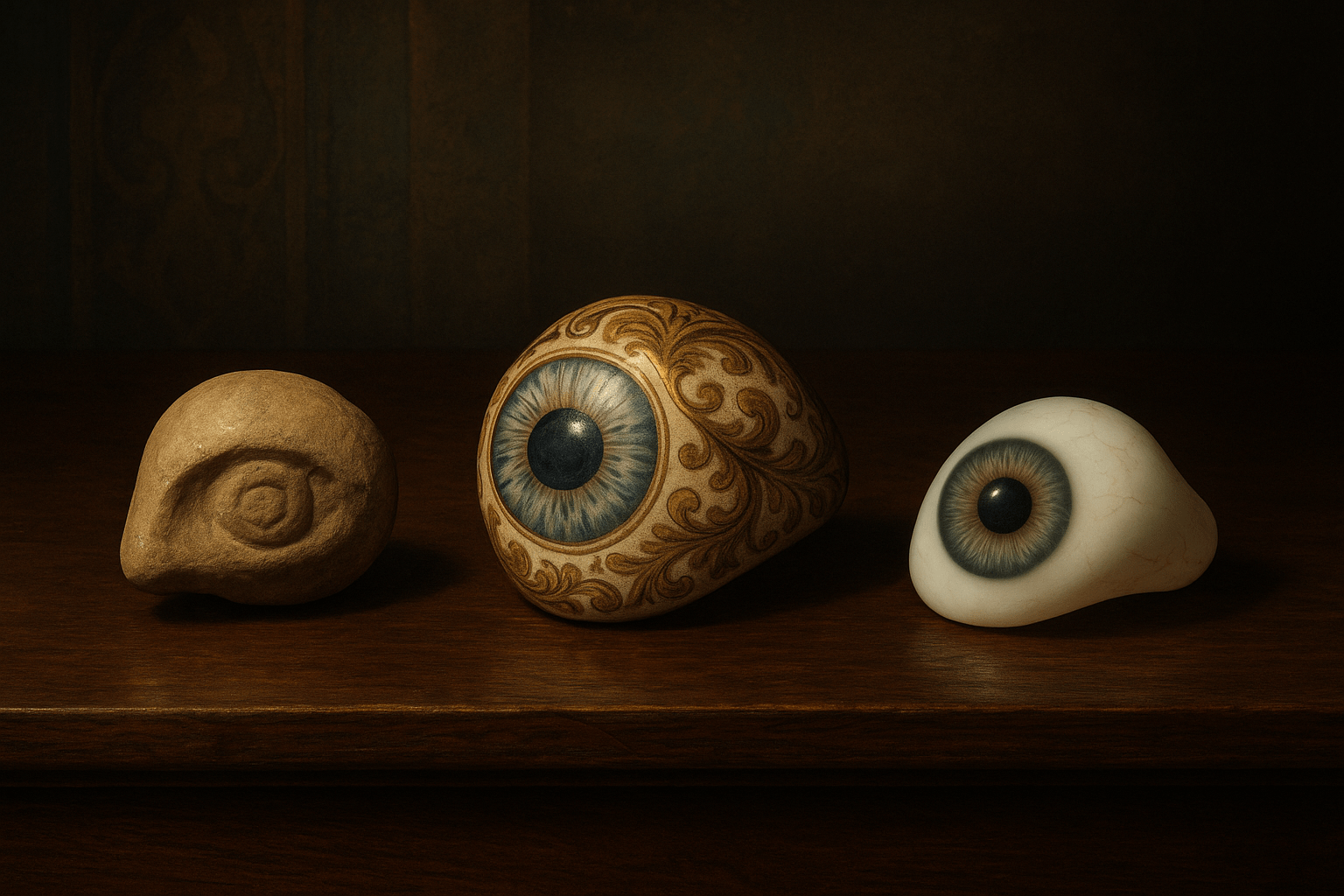

The earliest known artificial eye dates back to nearly 5,000 years ago. Unearthed in modern-day Iran at a site known as Shahr-i Sokhta, or the “Burnt City”, archaeologists discovered the skull of a woman from a wealthy class, dated to 2900-2800 BCE. Nestled in her eye socket was a hemisphere made of a lightweight bitumen paste, coated with a thin layer of gold. Intricately engraved with a central iris and radiating lines like sun rays, it was held in place by fine gold threads passing through tiny drilled holes. While groundbreaking, this was not a functional prosthetic that fit within the socket tissues; it was likely worn over the disfigured area or was a funerary object intended to complete the body for the afterlife.

This idea of spiritual, rather than practical, restoration was common in the ancient world. The Egyptians, masters of funerary arts, placed artificial eyes made of clay, precious stones, or painted linen into statues and mummies. These were not meant for the living but were designed to allow the deceased to “see” in the afterlife, reflecting their belief in the integrity of the body for spiritual passage.

The Crude Cosmetics of Rome

The first attempts at wearable prosthetics for the living were rudimentary and uncomfortable. Roman and Greek physicians created what were known as ectblepharon. These were typically made of painted clay or cloth, shaped into a convex shell that could be crudely placed inside the socket. The renowned 16th-century surgeon Ambroise Paré later described these early devices, noting they were often held in place by wires or external bands. Unhygienic and ill-fitting, they were purely cosmetic, offering a fleeting illusion of normalcy but causing significant irritation and offering no movement.

A Renaissance Revolution: The Glass Masters of Venice

The true “glass eye” as we imagine it was born from the fiery furnaces of Renaissance Venice. By the late 15th century, Venetian glassblowers, already world-famous for their unparalleled skill, turned their attention to ocular prosthetics. They developed a new technique for crafting hollow glass spheres, a significant leap from the heavy, solid prosthetics of the past.

The artistry was breathtaking. Instead of painting the front, they painted the iris and pupil on the back of the glass sphere before sealing it. This created a remarkable sense of depth and realism. To mimic the blood vessels of the sclera (the white of the eye), they would carefully fuse tiny red glass filaments onto the surface. These Venetian eyes were works of art, but they were far from perfect. Known colloquially as “thief’s eyes” because they could “steal a glance” without betraying their artificial nature, they had serious drawbacks:

- Fragility: Being made of glass, they could easily shatter.

- Discomfort: The glass used had a high lead content, which reacted with the fluids in the eye socket, causing the surface to become rough and abrasive over time.

- Tissue Damage: The sharp, unpolished edges of the glass could severely damage the delicate socket tissues with prolonged wear.

A German Breakthrough: The Cryolite Reform Eye

For centuries, the Venetian method remained the standard, despite its flaws. The next major innovation came in the early 19th century from the small German town of Lauscha, a hub for glass manufacturing. A glassblower named Ludwig Müller-Uri was driven by a personal mission—several of his own children suffered from eye defects. He was determined to create a more comfortable and durable prosthetic.

Around 1835, after much experimentation, Müller-Uri developed a superior type of glass known as cryolite glass. This new material had a significantly lower lead content and was far more resistant to the corrosive effects of the body’s natural fluids. It remained smooth and was much kinder to the sensitive eye socket, allowing for comfortable long-term wear for the first time in history. This “Reform Eye” revolutionized the industry, and Lauscha, Germany, quickly supplanted Venice as the world’s center for artificial eye production, a title it would hold for over a century.

The Demands of War and the Dawn of Acrylic

The next great leap was not driven by artistry, but by conflict. During World War II, the global supply of high-grade German glass was cut off from the Allied nations. With a sudden and urgent need to provide prosthetics for soldiers returning from the front, American and British medical professionals were forced to innovate.

The answer came from an unlikely field: dentistry. U.S. Army dental technicians began experimenting with polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), better known as acrylic—the same durable plastic used to make dentures. The results were transformative. Acrylic offered numerous advantages over glass:

- It was virtually shatterproof.

- It was significantly lighter, reducing strain on the lower eyelid.

- It could be molded from a direct impression of the patient’s socket, resulting in a truly custom and comfortable fit.

- It was easy to modify and repolish, allowing for adjustments over time.

This marked a fundamental shift in the field. The creation of an artificial eye moved from the hands of the glassblower to the clinical environment of the ocularist, blending medical science with detailed craftsmanship.

The Modern Ocularist: A Blend of Art and Science

Today, the creation of an ocular prosthetic is a meticulous process performed by a highly skilled professional known as an ocularist. The process begins by taking an impression of the individual’s eye socket to create a perfectly fitted base shell. The true artistry follows, as the ocularist hand-paints the acrylic to precisely match the patient’s remaining eye. Using layers of specialized paints, they replicate the unique color, pattern, and depth of the iris. Tiny red silk threads are often embedded into the acrylic to mimic the delicate blood vessels of the sclera. The result is a hyper-realistic prosthetic that is virtually indistinguishable from a natural eye, moving in sync with the healthy eye and restoring a profound sense of confidence and wholeness to the wearer.

From a gold-plated bauble in an ancient tomb to a custom-molded, hand-painted piece of medical art, the history of the artificial eye is a testament to human ingenuity. It’s a journey that tracks our evolving understanding of materials, medicine, and the timeless, deeply human quest to restore not just what is lost, but the very window to our identity.