Imagine a world where a sudden, debilitating fever isn’t caused by a virus, but by a curse. Picture a difficult childbirth where the true danger isn’t a medical complication, but the hovering spirit of a jealous rival. This was the reality for the aristocrats of Japan’s Heian period (794-1185 CE). In the gilded halls and perfumed chambers of the imperial court in Heian-kyō (modern-day Kyoto), a deeply ingrained belief held that powerful, vengeful spirits—known as mononoke—could possess the living, causing sickness, madness, and even death.

This wasn’t mere superstition or quaint folklore. The fear of mononoke was a powerful force that shaped medicine, fueled political paranoia, and gave rise to elaborate spiritual warfare. Far from a simple ghost story, this belief provides a crucial window into the psychological and social anxieties of one of the most refined civilizations in world history.

What, Exactly, Was a ‘Mononoke’?

The term mononoke (物の怪) is deceptively simple. It combines the characters for “thing” (mono) and “spirit” (ke), essentially meaning a malevolent spiritual entity. But unlike the Western concept of a ghost, a mononoke wasn’t always the spirit of someone who had already died (a shiryō). More terrifyingly, it could be the spirit of a living person (an ikiryō).

The Heian aristocracy believed that intense, unresolved emotions—particularly jealousy, thwarted ambition, grief, or rage—could cause a person’s spirit to detach from their body. Often happening unconsciously while the person slept or was lost in thought, this wandering spirit would seek out the object of its obsession and inflict harm. The source of the spirit might be entirely unaware of the havoc their spectral self was wreaking. The true source of a mononoke was therefore not death, but the untamable power of human emotion.

The Tale of Genji: Lady Rokujō’s Wrath

Nowhere is the concept of the mononoke more vividly and famously depicted than in Murasaki Shikibu’s 11th-century masterpiece, “The Tale of Genji.” The story provides a perfect case study in the character of Lady Rokujō, a proud, high-ranking imperial consort spurned by the tale’s hero, Prince Genji.

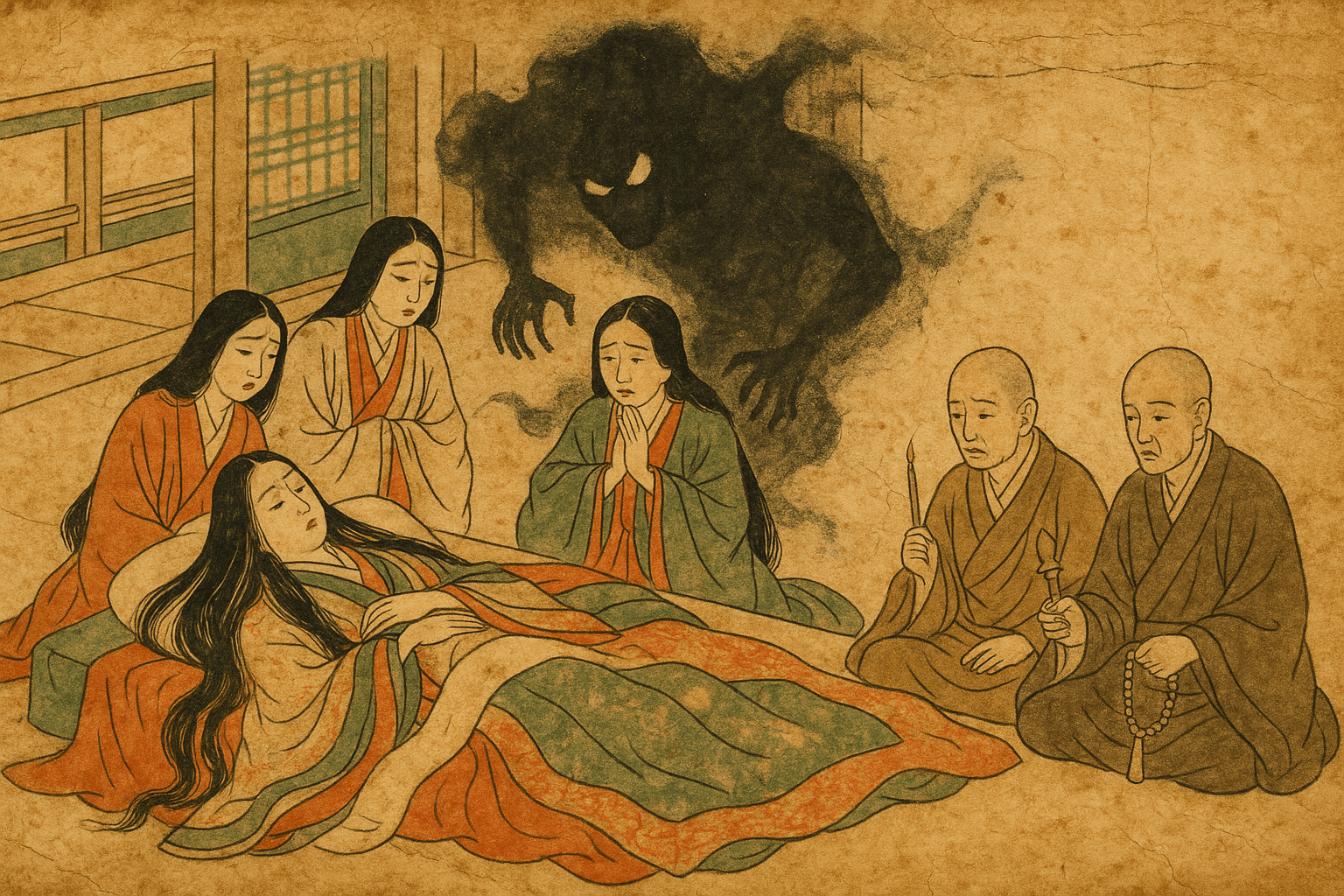

Consumed by humiliation and jealousy over Genji’s affection for other women, Lady Rokujō’s powerful ikiryō (living spirit) becomes a terrifyingly effective weapon. First, it attacks and possesses Genji’s pregnant wife, Lady Aoi. During Aoi’s excruciatingly difficult labor, she cries out in Rokujō’s voice, and the possessing spirit is only temporarily subdued by Buddhist rites. Shortly after giving birth, Aoi dies, her death universally attributed to Rokujō’s vengeful spirit. Later, the same spirit—now a shiryō after Rokujō’s death—returns to torment and eventually kill Genji’s most beloved consort, Murasaki. For Heian readers, this wasn’t fantasy; it was a chillingly realistic portrayal of their deepest fears.

Sickness and Spirit: When Medicine Met Metaphysics

In an era before germ theory, the mononoke provided a primary diagnostic framework for illness. Any sudden malady, from persistent fevers and delirium to psychological distress and complications in childbirth, was a potential case of spiritual possession. Consequently, the roles of doctor and priest were inextricably linked.

When a high-ranking courtier fell ill, the first step wasn’t just to administer herbal remedies, but to perform a spiritual investigation. The “treatment” often involved a medium, typically a young woman, who would be used as a vessel to draw the possessing spirit out of the victim. Once transferred, the mononoke would speak through the medium, identifying itself and, more importantly, airing its grievances. This “confession” was the crucial diagnostic moment. Only by knowing the spirit’s identity and the source of its anger could the proper countermeasures be taken. A patient’s recovery depended not on medicine alone, but on a successful negotiation with an angry spirit.

The Politics of Possession

In the cloistered, competitive world of the Heian court, where marriage alliances and imperial favor dictated one’s fortune, the belief in mononoke had profound political implications. An accusation of spiritual assault was a powerful weapon.

Imagine your political rival’s daughter falls gravely ill. During the exorcism ritual, the possessing spirit is identified as your recently deceased and disgruntled aunt. The implication is clear: your family harbors a grudge so deep it has manifested as a spiritual attack. Such an event could lead to social disgrace, loss of rank, and political ruin. The fear of being the source of a mononoke, or being targeted by one, added a layer of supernatural dread to every courtly intrigue and rivalry. Diaries from the period, such as that of the powerful statesman Fujiwara no Michinaga, are filled with references to commissioning rites to protect against curses and spirits sent by political enemies.

Waging War on Spirits: Exorcism and Placation

Once a mononoke was identified, a full-scale spiritual battle commenced. The goal was twofold: drive the spirit away from its victim and, if possible, placate its anger to prevent it from returning. This required a team of spiritual specialists.

- Buddhist Monks: These were the front-line soldiers. Accomplished clerics, often from powerful mountain temples, were summoned to the patient’s bedside. They would perform continuous, sometimes days-long ceremonies, chanting powerful sutras (like the Lotus Sutra) and performing esoteric rites to create a spiritual barrier and overwhelm the mononoke with the force of Buddhist Law.

- Onmyōji (Masters of Yin-Yang): These experts in divination and cosmology were spiritual detectives and protectors. They used their knowledge of cosmic forces to identify auspicious and inauspicious directions, create protective amulets, and perform purification rituals to cleanse the afflicted person’s residence.

The scene of an exorcism was one of intense sensory overload—the loud droning of sutras, the scent of incense, the dramatic gestures of holy men—all designed to make the host body an intolerable environment for the possessing spirit. If the spirit was particularly stubborn, placation was attempted. This might involve sponsoring memorial services for the spirit, making offerings at specific temples, or even securing a posthumous promotion in court rank for the deceased to soothe their wounded pride.

The belief in mononoke eventually faded as Japan’s political and social structures changed, but its legacy endures. It reminds us that for the courtiers of Heian Japan, the internal world of emotion was just as real and dangerous as the external world of politics. It was a worldview in which a broken heart could become a lethal weapon and a lingering grudge could manifest as a deadly fever, forever linking the fragility of the body to the formidable power of the human spirit.