Imagine a time when the world’s most sought-after commodity wasn’t gold, oil, or diamonds, but bird droppings. Mountains of it, piled hundreds of feet high on desolate islands, were worth a fortune. This was the Guano Age, a bizarre and forgotten chapter of the 19th century when nations went to war, fortunes were made, and the global balance of power shifted—all over the pursuit of nutrient-rich seabird excrement.

In the early 1800s, Europe and North America faced a looming crisis. Centuries of intensive farming had leached the soil of its essential nutrients. Crop yields were plummeting, and with a rapidly growing population fueled by the Industrial Revolution, the threat of widespread famine was very real. Farmers tried everything from animal manure to crushed bones, but these fertilizers were inefficient and scarce. The world desperately needed a super-food for its soil, and it found it in the most unlikely of places: the rainless coasts of Peru.

The Unlikely Treasure of the Pacific

For centuries, the arid Chincha Islands off the coast of Peru had been home to millions of Guanay cormorants, Peruvian boobies, and pelicans. In this unique, rain-free environment, their droppings didn’t wash away. Instead, they accumulated and fossilized over thousands of years, creating compacted mountains of a substance the local Quechua people called wanu, or guano.

While indigenous populations and Spanish colonists had long used guano on a small scale, its true power was revealed to the wider world by Prussian explorer Alexander von Humboldt. In 1804, he studied the substance and sent samples back to Europe. The chemical analysis was astounding. Guano contained an incredibly high concentration of the three ingredients essential for plant growth:

- Nitrogen: Crucial for leafy growth.

- Phosphate: Essential for root and flower development.

- Potassium: Important for overall plant health and water retention.

Compared to the best European farmyard manure, Peruvian guano was over 30 times more potent. It was, quite literally, agricultural dynamite.

From Scientific Curiosity to Global Frenzy

The first commercial shipment of guano arrived in Britain in 1840. The results were nothing short of miraculous. Farmers reported doubling or even tripling their crop yields. Wheat grew taller, turnips grew larger, and barren fields turned vibrant and green. Word spread like wildfire, and demand exploded. Guano became known as “white gold.”

The Peruvian government, realizing it was sitting on a literal mountain of money, swiftly declared a state monopoly. They nationalized the Chincha Islands and established a system of consignees—private firms, mostly British, that would manage the extraction and sale of guano abroad for a share of the profits. From the 1840s to the 1870s, Peru was almost entirely funded by bird droppings. This period, known as the “Guano Age”, saw the country’s treasury overflow. The government paid off its foreign debt, abolished slavery and indigenous tributes, and funded massive public works projects. It was a period of unprecedented national wealth, all built on a foundation of guano.

The Dark Side of White Gold

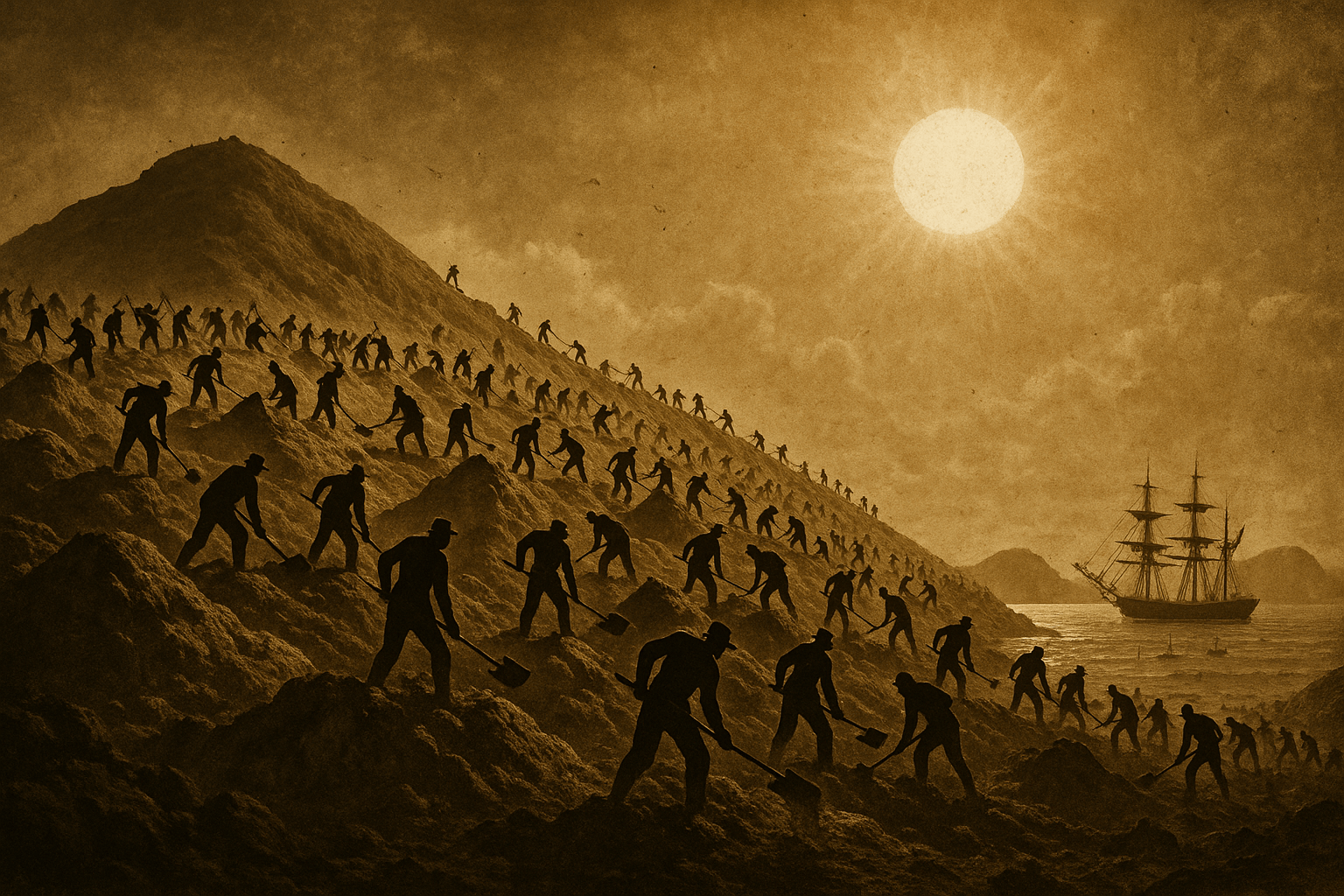

But this boom came at a horrific human cost. Harvesting guano was brutal, dangerous work. The mountains of dung had to be hacked apart with picks and shovels under a relentless sun. The air was thick with choking, ammonia-filled dust that burned the eyes and lungs. Workers lived in squalid conditions on the barren islands, far from civilization.

Exploitation and Slavery

Few people would do this work voluntarily. At first, Peru used convicts and army deserters. When that proved insufficient, the government turned to a more sinister source of labor: indentured Chinese workers, often called “coolies.” Tens of thousands of men were lured from China with false promises of good wages, only to find themselves trapped in a system of debt peonage that was little better than slavery. They were worked to exhaustion, beaten by overseers, and suffered from disease and malnutrition. Many took their own lives rather than endure the living hell of the guano pits.

Imperialism and Conflict

The immense value of guano also fanned the flames of international competition. The United States, eager to secure its own supply for its vast farmlands, passed one of the most curious laws in its history: the Guano Islands Act of 1856.

This act empowered any American citizen to claim an uninhabited, unclaimed island containing guano deposits for the United States. It was a license for private citizens to carry out American expansionism. Under this act, the U.S. claimed nearly 100 islands across the Pacific and Caribbean, including Baker Island, Howland Island (famous as Amelia Earhart’s intended destination), and Navassa Island. It was a clear example of resource-driven imperialism, setting a precedent for future American interventions abroad.

The ultimate conflict over these fertilizers erupted in South America. The War of the Pacific (1879-1884) saw Chile go to war with an allied Peru and Bolivia. While often called the “Nitrate War”, its roots were firmly planted in the guano trade as well. The conflict was over control of the Atacama Desert, which held not only the world’s richest nitrate deposits but also valuable guano reserves. Chile emerged victorious, annexing Peruvian territory and seizing control of the region’s mineral wealth, leaving Peru economically devastated.

The End of an Era

Like all resource booms based on finite materials, the Guano Age couldn’t last forever. Decades of frenzied, unsustainable mining had stripped the Chincha Islands bare by the 1870s. The once-mighty mountains of white gold were gone. Peru, having squandered much of its guano wealth and then lost its remaining nitrate resources to Chile, plunged into a deep economic depression.

The final nail in the coffin came from science. In the early 20th century, German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed the Haber-Bosch process, a revolutionary industrial method for synthesizing ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen. This meant fertilizers could now be created cheaply and in limitless quantities in a factory. The age of synthetic fertilizers had begun, and natural guano was rendered almost instantly obsolete as a global commodity.

Today, the Guano Age is a largely forgotten footnote in history. Yet its legacy is profound. It transformed global agriculture, fueled the first wave of American overseas expansion, created and destroyed national economies, and caused immense human suffering. It’s a powerful reminder that history’s greatest turning points can be driven by the most mundane of substances—even something as simple as bird droppings.