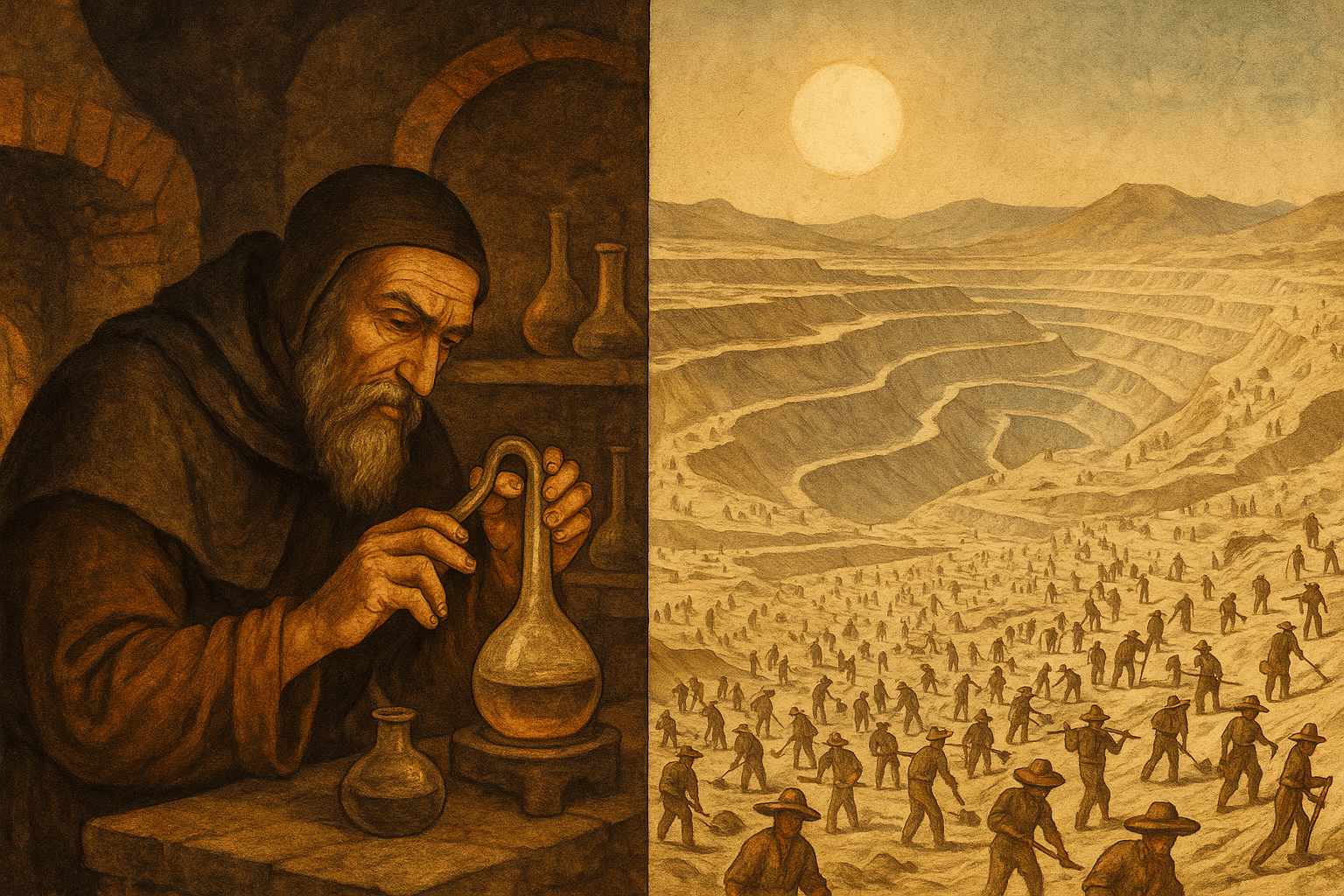

The Secret of “Fire Drug”

Gunpowder, one of China’s Four Great Inventions, was likely discovered by Taoist alchemists searching for an elixir of immortality around the 9th century. They found instead a “fire drug” (hu藥 yào) that burned with explosive force. The recipe they perfected consisted of three ingredients: charcoal (fuel), sulfur (fuel and stabilizer), and saltpeter (the oxidizer). While all are necessary, saltpeter is the secret sauce. It supplies the oxygen that allows the mixture to burn almost instantaneously, even in a confined space like a gun barrel, creating the massive volume of hot gas needed for propulsion.

Early Chinese sources of saltpeter were modest, often scraped from soil rich in animal waste or harvested as crystalline deposits from cave walls where bat guano had decomposed. As the military applications of gunpowder became clear, the demand grew, and control over its ingredients became a matter of state security.

Europe’s Desperate Scramble: The “Niter Man”

When gunpowder technology spread westward along the Silk Road, arriving in Europe by the 13th century, it revolutionized warfare. But European leaders quickly ran into a critical problem: a severe lack of natural saltpeter. Unlike in parts of Asia, large, naturally occurring deposits were virtually non-existent.

This scarcity led to one of the most intrusive and unpopular state-sanctioned professions in history: the “saltpeter man” or “pétrier.” Since saltpeter forms from the decomposition of organic matter, particularly nitrogen-rich waste like urine and manure, the best sources were man-made. Saltpeter men were granted royal authority to enter any private property—homes, stables, cellars, dovecotes, even churches—to claim soil they deemed ripe for harvesting. They would dig up earthen floors and scrape the grime from stone walls, leaving behind a mess and resentful citizens. In Elizabethan England, the saltpeter man’s commission gave him almost unlimited power to commandeer carts and dig wherever he pleased, a necessity for defending the realm against the Spanish Armada but a constant grievance for the common person.

The collected “niter-earth” was then taken to a processing facility. It was leached with water to dissolve the nitrates. This solution was then mixed with potash (potassium carbonate), typically derived from wood ash. This crucial chemical step converted the less-stable calcium nitrate from the soil into the prized potassium nitrate. The final solution was boiled down and cooled, allowing the white crystals of pure saltpeter to form.

The Birth of Industrial Niter

As armies grew larger and firearms more common, scraping cellar floors became woefully insufficient. Nations began to rationalize and industrialize saltpeter production. Starting in the 17th century, countries like Sweden and France established “niter beds” or “saltpeter plantations.” These were large, purpose-built heaps of manure, soil, straw, and organic waste, carefully tended and aerated to optimize the growth of nitrate-producing bacteria. They were, in effect, state-sponsored compost piles for creating munitions.

On the eve of the French Revolution, the brilliant chemist Antoine Lavoisier was put in charge of France’s Gunpowder and Saltpeter Administration. Applying scientific principles, he dramatically improved the efficiency of niter bed production, ensuring that the revolutionary armies—and later, Napoleon’s Grande Armée—were well-supplied with the gunpowder they needed to conquer Europe.

White Gold in the Atacama

The 19th century brought a dramatic shift in the global saltpeter trade. The game-changing discovery was not of potassium nitrate, but of massive, mineral-rich deposits of sodium nitrate (NaNO₃) in the Atacama Desert, the driest place on Earth. This “Chile saltpeter”, found in a raw mineral form called caliche, covered a vast territory then belonging to Peru and Bolivia.

This discovery was revolutionary. The ore could be mined on an industrial scale and, though slightly less effective than potassium nitrate, could be used in many gunpowder formulations or easily converted to the superior form. The immense value of these nitrate fields led directly to the War of the Pacific (1879-1884). Chile, backed by foreign capital, went to war with both Peru and Bolivia for control of the resource. Chile’s victory was total; it annexed the nitrate-rich provinces, leaving Bolivia landlocked and creating a Chilean monopoly on the world’s most important military resource.

For the next four decades, the “Nitrate Era” fueled Chile’s economy and the arsenals of the great powers. British, German, and American companies invested heavily, creating sprawling mining towns in the desolate desert. The immense profits built mansions in Valparaíso and funded Europe’s escalating arms race in the lead-up to World War I.

Synthesized from Thin Air

The final chapter in the story of saltpeter was written not in a mine, but in a laboratory. German military planners, acutely aware that a British naval blockade would cut off their supply of Chilean saltpeter in a future war, saw this dependence as a fatal strategic weakness. They poured resources into finding a synthetic alternative.

The breakthrough came from chemist Fritz Haber, who in 1909 developed a process for synthesizing ammonia from the nitrogen and hydrogen in the air. Engineer Carl Bosch later scaled this up for industrial production. The Haber-Bosch process, one of the most significant scientific inventions of the 20th century, allowed Germany to mass-produce nitrates for both fertilizers and explosives. When World War I broke out and the Royal Navy blockaded German ports as expected, Germany’s ability to create its own saltpeter from thin air allowed it to sustain its war effort for years.

The Haber-Bosch process instantly broke Chile’s monopoly. The Atacama nitrate industry collapsed, turning the once-bustling mining towns into decaying ghost towns. The age of hunting for saltpeter in the ground was over. The quest that began with scraping filth from walls, that fueled empires and sparked wars for a “white gold”, had been rendered obsolete by chemists who had learned to conjure bombs and bread from the air itself.